Forget the Stones: Beatles vs. Bond was the real British rivalry, per a new book

Review

Love and Let Die: James Bond, the Beatles, and the British Psyche

By John Higgs

Pegasus: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

On Oct. 4, 1962, the Soviet Union installed its first nuclear missile in Cuba and the world braced for a potential war between its two superpowers. One day later, in England, another clash between two emerging hegemons was about to begin in earnest.

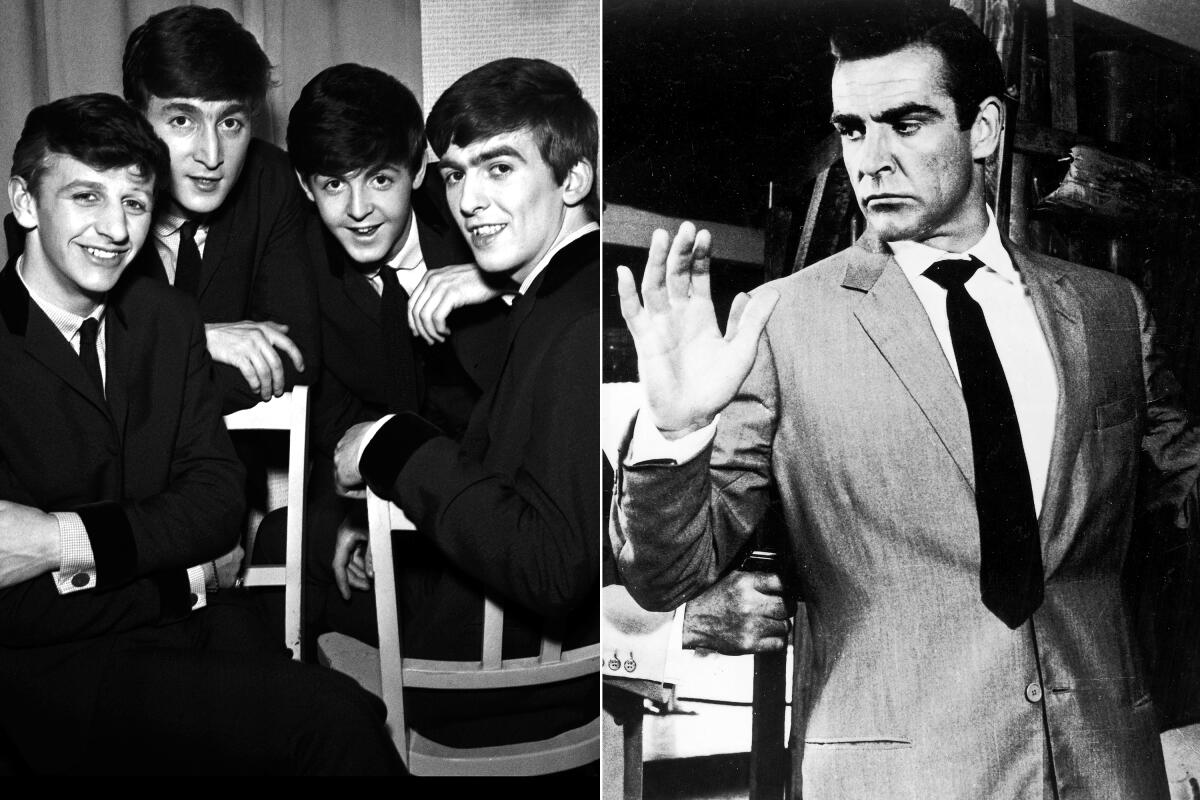

On that day, the Beatles released their first single, “Love Me Do,” and the first James Bond film, “Dr. No,” premiered in London. For John Higgs, author of the new book “Love and Let Die,” this confluence of events is its own neutron bomb, the moment when England found itself confronted with two opposing views of itself: Bond a metaphor for a colonial power clinging to the last vestiges of its brawn in the wake of the Second World War, and a younger generation of Beatles fans poised to unshackle itself from all the Empire stood for, particularly its notions of class and privilege. The Beatles and Bond opened a chasm in the culture, a “crisis of masculinity” that Higgs tries dutifully to unpack.

Today, as estranged royals battle over a wounded monarchy and the erstwhile Empire muddles through its self-estrangement from Europe, the question of how Britannia perceives itself feels timely, even urgent.

“Love and Let Die,” alas, is an intermittently fascinating but lumpy cultural history. Higgs posits that Bond and the Beatles represent the Janus face of early ’60s England. Tracing the arc of these two cultural behemoths running on parallel tracks, he wades through a lot of familiar territory for his flashes of insight. He is right, however, when he asserts that “imagination matters because ideas alter beliefs” and “beliefs shape attitudes.”

Working with a free hand, the director included previously unseen George Harrison quitting the band and was able to isolate moments of conversation away from the sounds of guitars and amps.

Sixty years on, it’s difficult to imagine the anodyne “Love Me Do” as a transgressive act, but it wasn’t so much the song as the idea of the Beatles that unsettled Britain’s ruling class. The four band members were low-born Northerners from a dingy port town with no formal education; their success was against the natural order of things, an act of effrontery. Bond, in contrast, was an establishment man in service to the queen, an Eton-educated, sexy killing machine whose brief was to save the world while indulging in the best the world has to offer. The planet’s most famous band and the most enduring movie spy thus represent for Higgs a rent in the social fabric of a country that for so long had regarded class as destiny.

The soul of James Bond can be traced back to his creator, author Ian Fleming. Born into one of the U.K.’s most prominent banking families, Fleming was raised by a socialite who couldn’t be bothered with him. (His father was killed in World War I; Winston Churchill wrote his obituary.) Shunted off to various elite schools including Bond’s Eton, Fleming developed a taste for Bond-like voluptuary pleasures.

His destiny was laid out before him in shades of beige: marriage and a family, a high-ranking job in the civil service. Fleming became engaged to a woman he didn’t love and found himself moving toward glum respectability — until he created secret agent 007. The James Bond novels were an act of self-creation on the page; Higgs writes that Bond would become Fleming’s “avatar … with the same tastes, background, opinions and prejudices, but with none of the troubles that weighed so heavily on him — an unashamedly unemotional masculine fantasy.”

Bond, in Higgs’ view, was Fleming’s response to the attenuation of England’s colonial might, its weakening global pulse. As personified by Sean Connery, he was a super spy who would embody the country’s exceptionalist virtues, which for Fleming included a callous disregard for women and ethnic minorities. Racism and sexism are casually embedded in Fleming’s novels — a dark mirror held up to a retrograde worldview that the Beatles were in the process of dismantling.

Daniel Craig’s final James Bond adventure is a classic blend of fresh and familiar, and it arrives just as cinemas need it the most.

The comely female characters in Fleming’s Bond stories are more props than people, a diversion until they are a nuisance. “Fleming wanted to sleep with glamorous, exciting women,” writes Higgs. “Then he just wanted them to disappear afterwards.” The body count among Bond’s lovers is alarmingly high: “Bond is death and must always be so. The women he touches, therefore, must die.” Here was British machismo immune from mockery, the prewar vision of England that Fleming wanted to project onto a world turned upside-down — a world, in short, where the Beatles could become stars.

Within the context of Fleming’s England, Higgs’ Beatles were bomb-throwers laying waste to all that was virtuous in the aristocratic British soul. “It didn’t worry me that the Empire was crumbling,” Paul McCartney mused in an interview with Barry Miles excerpted here. “I thought it was a good thing. I was very pleased to see that old regime get out.”

Contemptuous of tradition and lineage, massively successful despite not having been educated in the finishing schools of Fleming’s youth, McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr brushed off British propriety as a relic. Even a song like “Can’t Buy Me Love,” Higgs argues, is a shot across the bow, money being “a secondary concern” as it can be used only for material ends. How un-Bond-like of them.

The culture bent to the Beatles, of course. Even Prime Minister Harold Wilson called himself a fan. And yet Bond’s regressive maleness thrived in films that grossed billions worldwide, while the Beatles became secular saints, beloved and immortal, light-years away from the insurrectionists of 1962. Eventually McCartney succumbed to Bond’s remunerative charms by writing the theme song for the 1973 Bond film “Live and Let Die,” his first major hit as a solo artist.

In an entry from his COVID-19 diary “What Just Happened,” out Nov. 9, critic and novelist Charles Finch binges on the Beatles and reaches a turning point.

So who won the war for the British psyche? Higgs can’t really say, opting for some muddy middle ground between Bond’s self-confident swagger and the Beatles’ emotional intelligence. This prevaricating doesn’t do Higgs any favors. His intriguing thesis winds up losing steam about halfway through the book, when “Love and Let Die” alternates between a fairly detailed history of the Bond franchise and the story of the Beatles — the latter being one of the most familiar narratives of the 20th century. There are also niggling errors: Harrison wrote a song called “Apple Scruffs,” not “Apple Scrubs.” Higgs is on to something here, but with “Love and Let Die,” he doesn’t quite deliver on an alluring premise that prompts some fundamental questions about the soul of Britain.

Weingarten is the author of “Thirsty: William Mulholland, California Water, and the Real Chinatown.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.