What novelist Cai Emmons taught us about how to die

Cai Emmons, novelist and playwright, was furiously busy in the months leading up to her death Monday at age 71. But she might well be best remembered for a blog she maintained after she was diagnosed with bulbar-onset amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on Feb. 4, 2021.

In a series of posts, she candidly discussed the changes in her physical self while also celebrating moments of joy. She wrote of her willingness to hold nothing back, to mend past rifts, to focus on moments of beauty and to note the sublimity of a life well lived. As she wrote in her last post on Dec. 28, “I wanted to devour the world, do it all, even with the end in sight.”

In late November, Cai took a guided psychedelic mushroom trip intended to make her comfortable with the physical process of dying. “When the mushrooms took hold,” she wrote, “I imagined shedding my body, wriggling out of it like a worm offloading a thick skin, then hovering above as I watched myself being carried away.” Shortly thereafter, she asserted her right to die under Oregon’s Death With Dignity law and was granted authorization by her doctors.

A drug trip to explore what death might feel like was in character for a woman with boundless curiosity. Whether she was recounting her love for skinny-dipping, playing practical jokes or plunging into a new writing project, her sense of play and humor endeared her to friends and readers.

Emmons, whose novels explored topics including women’s rage, maternal love and grief for a planet in crisis and whose most recent novels, “Livid” and “Unleashed,” were both published in September, died surrounded by family members and friends at her home in Eugene.

“Cai Emmons ended her remarkable life today,” read a statement released on Twitter by her family Monday. “She faced her final days with clarity, untold amounts of bravery, and entirely on her own terms. She died as she lived, surrounded by love.”

Cai Emmons discusses being diagnosed with ALS shortly after finishing the surrealist California novel “Unleashed,” one of two novels out this September.

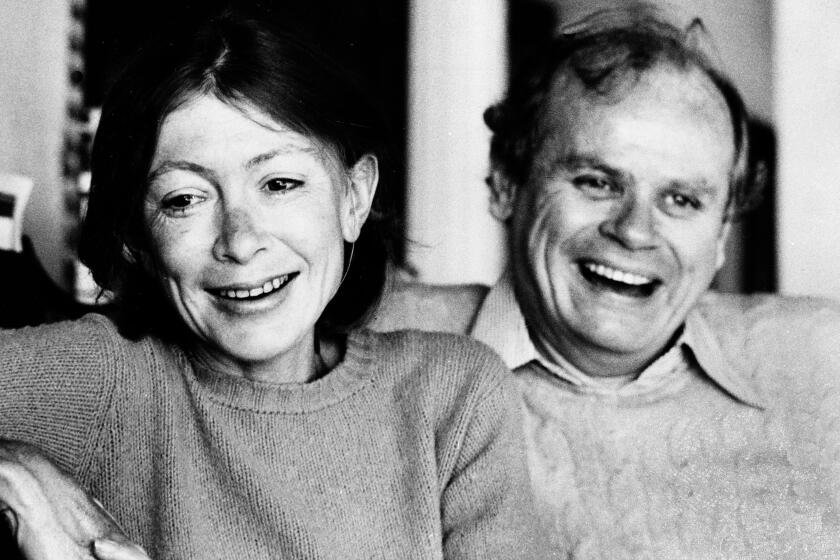

To the end, Emmons was making new friends, and I consider myself exceedingly fortunate to have become one of them. I first met Cai and her husband, playwright Paul Calandrino, in August when I interviewed her for a profile in The Times. We sat on a patio surrounded by flowers and buzzed by hummingbirds, communicating with the help of Emmons’ speech synthesizer. Several hours passed as we discussed her writing career, her political passions and her 20-plus-year partnership with Calandrino, whom she wed shortly after her diagnosis. One of my best memories of that afternoon is the sound of Cai’s frequent laughter.

Emmons was born Jan. 15, 1951, in Boston and grew up in Lincoln, Mass. She graduated from Yale before earning an MFA in film from New York University and another in fiction from the University of Oregon. She taught at USC before joining the faculty of the University of Oregon, teaching fiction and screenwriting from 2002 through 2018. A documentary about her by filmmaker Sandra Luckow is in production.

Initially a playwright, Emmons wrote the plays “Mergatroid” and “When Petulia Comes,” both staged in New York. In addition to a collection of short stories, she published six novels. “His Mother’s Son” (2003) was awarded the Oregon Book Award for fiction. Her 2018 eco-feminist novel, “Weather Woman,” was praised by KLCC-FM, the NPR affiliate in Eugene, for its “evocative writing and resonant themes” and for balancing “a thoughtful concern for the world” with “individual human concerns and passions that make a compelling story.”

Although “Unleashed,” which interweaves a mother’s grief over her only child leaving for college with the ravages of a Northern California wildfire, was written before her ALS diagnosis, Emmons felt it reflected her body’s awareness of the disease. “The novel was written over the year when I was losing my voice,” she noted. “It seemed to run out of me, and it was so weird, but I didn’t care... That book seemed like something that was a roaring from my body.”

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

When we first spoke, she was working on a new novel, which she completed shortly before her death. Her newest work is an exploration of anger over the rise of fascism and nationalism in 21st century America. Cai rued the setbacks in movements toward gender rights and racial and social justice. She recognized that her growing sense of peace with dying had to be balanced with her passionate rage about injustices that would outlive her.

She also explored those themes on her blog. In response to a friend’s question about whether Cai was “a Pollyanna,” she said she was genuinely optimistic, because the presence of friends and family buoyed her. But, she noted, “I live in a state of cognitive dissonance, floating on my hammock of love as I watch humanity going down the tubes.”

Shortly after I interviewed Cai, I received an email inviting me and my husband to dinner. More meals soon followed. One of these occurred on the night of the midterm elections; we toasted as Cai was reassured that, at least for now, American democracy had been preserved. Her parents’ civil-rights activism inspired her first literary effort, a poem about racism. This November night, she shook her fist in triumph as various races were called.

On my last visit with her in mid-December, it was obvious that she had lost most of her physical strength. But as we spoke in her “cockpit,” the complete work space she had created in her bed, she still radiated ebullience as she recounted the richness of moments spent over Thanksgiving with those who now survive her — Paul and their son, Ben; her sisters and their families. The smallest caretaking interactions between Paul and Cai exhibited what you can only call true love. In one blog post, she wrote about Paul brushing her hair every day: “I close my eyes as he strokes and pats and fluffs. I would happily sit there all day under his gentle ministrations. The ritual has come to feel almost sacred.”

Deepti Kapoor’s “Age of Vice” comes bearing “Godfather” comparisons and an FX series deal. But in favoring glitz, the novel loses sight of India’s poor.

I feel honored that happenstance brought Cai into my life; watching her journey has changed me in ways I’m only now beginning to process. Shortly after 4 p.m. Monday, in my own house in Eugene, I watched wild cloud formations from my window and imagined that she was free and riding the wind. She died at 4:12 p.m.

In “Unleashed,” Cai wrote a passage that’s difficult not to read as her reckoning with those she would leave behind. “We would become for them a memory, or a dream they could make sense of and would ponder again and again, trying to understand … We imagined them wishing that they, too, might someday sample the satisfactions of a stripped and simple life.

“No grasping, no greed, no ambitions, no malice.

Enough. Gone. Full stop.

Sniff the glorious world.”

Berry writes for a number of publications and tweets @BerryFLW.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.