A complete, opinionated reader’s guide to Cormac McCarthy’s novels

On the Shelf

A Complete Cormac McCarthy Reader's Guide

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

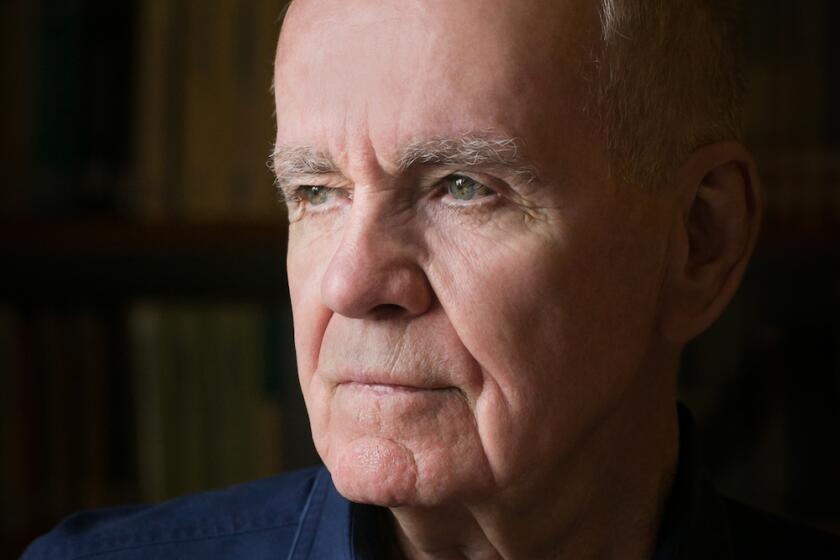

Cormac McCarthy published his first novel, “The Orchard Keeper,” in 1965. He was not quite 32, but already reckoning with many of the themes that have marked his work: sin and family and vengeance and complicity, as well as an abiding sense of place. Over the ensuing decades, McCarthy has written 11 more novels, including “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” his new pair of connected narratives.

“The Passenger” came out in October and “Stella Maris” follows on Tuesday. With the author approaching 90, it seems time for a reading guide, or at least a taxonomy. This is no simple task: McCarthy has been called a Southern writer and a Western writer, but his most recent books don’t really fit either category. Perhaps it is most accurate to say he is both all and none of the above, a sui generis talent whose fiction is marked by a restless quality of searching, of longing and loss.

This is not to say all his books are equally effective: I certainly have my preferences, and other readers will gravitate to different phases or aspects of his work. That’s because the key to his career is a kind of shape-shifting in which the concerns remain consistent but the approaches vary. This gives his oeuvre a shape, regardless of the success or failings of any one title. Those shared textures define his writing for me.

Cormac McCarthy’s ‘The Passenger’ and ‘Stella Maris’ display his brilliance in full, exploring math, physics and incest in a brother-sister story.

The classic (or Southern) period

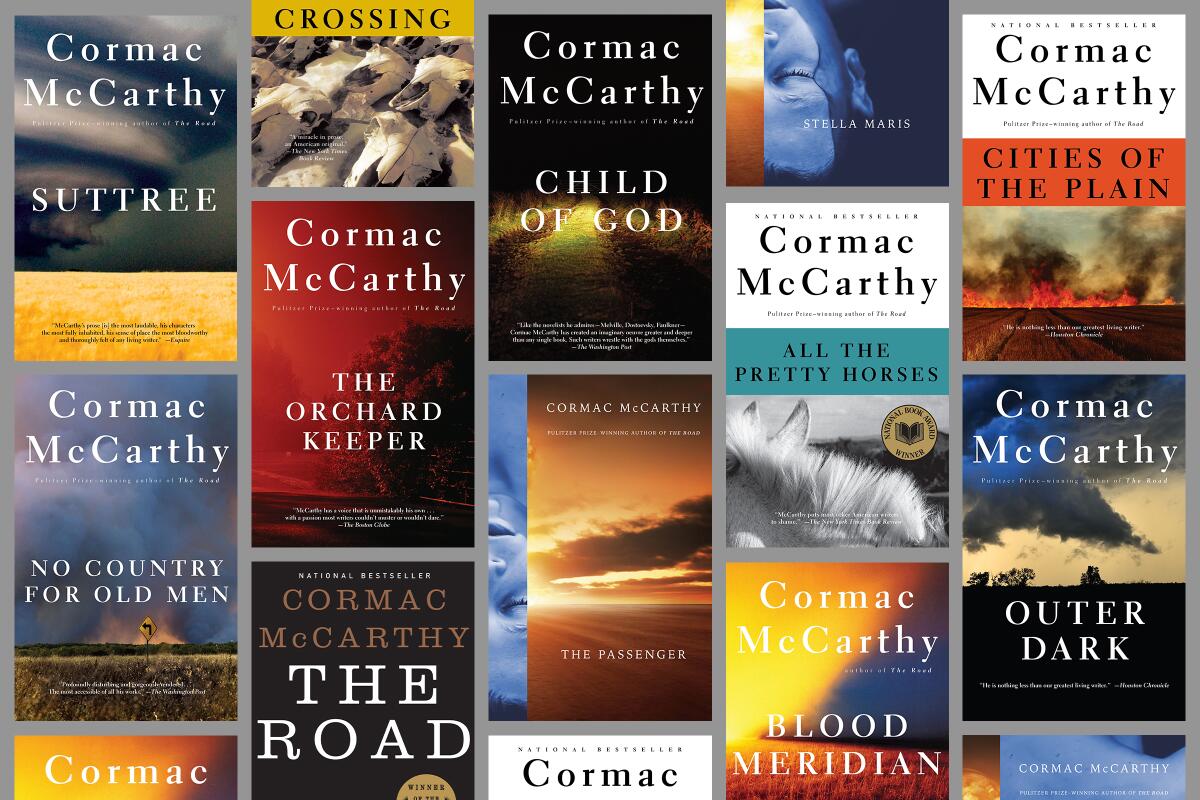

“The Orchard Keeper” (1965)

For a debut, the book is pretty solid. (It won the 1966 William Faulkner Foundation Award for first novel.) Set in Tennessee during the early part of the last century, it tells the story of a young man sworn to avenge his father’s murder, although as ever with McCarthy, the questions of guilt and redress are complicated by all the things we can never truly know. Though not his finest novel, it’s a vivid start.

“Outer Dark” (1968)

Bleak and unrelenting, McCarthy’s second novel may be the one I admire most. Biblical in its implications, it is a book in which a sister gives birth to her brother’s child and sets out in search of the baby after its father has abandoned it. Starkly amoral, with not a whisper of redemption, the novel contains the seeds of much the author would go on to write. Not least we see the roots of “The Road,” with its endless wandering across an apocalyptic landscape, and “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris,” which also deals with an incestuous dynamic that is deeply disquieting.

“Child of God” (1973)

On the heels of “Outer Dark,” McCarthy delivers another dark and pitiless work that recounts the story of a violent drifter: the titular “child of god.” McCarthy is firing on all cylinders here as he challenges our sense of faith and sanctity and even God’s benevolence, forcing us to face a world in which there is no real goodness or redemption, just one moment of death or pillage after another — suggesting that despair and degradation are the common lot of humankind.

“Suttree” (1979)

The last of the Southern novels offers a variation of a sort: longer and more linguistically ambitious, a rambling picaresque set in Knoxville during the 1950s, revolving around a man who has turned his back on his privileged upbringing to live among society’s forgotten. This may or may not be a moral stance, but like McCarthy’s earlier work, it addresses questions of fate and desolation — even as it meanders and sprawls. “From all old seam throats of elders, musty books,” he writes, “I’ve salvaged not a word.”

Cormac McCarthy’s rugged road to respectability

The middle (or Western) period

“Blood Meridian” (1985)

Widely considered his masterpiece, “Blood Meridian” is a hinge book in its way. While it is set along the Texas-Mexico border during the 1850s, its concerns have more to do with the brutality of the Southern novels than with the more elegiac tone of the later Western books. Here McCarthy presents apocalypse as a peculiarly American state of being, following a 14-year-old known only as the kid as he travels with the Glanton gang, who roamed the region massacring Indigenous people. Along with “Outer Dark” and “Child of God,” it’s among his greatest works.

“All the Pretty Horses” (1992)

The book that made McCarthy famous, or something like that, this first volume of the “Border Trilogy” takes place a century after “Blood Meridian.” Two teenage boys, John Grady Cole and his friend Lacey Rawlins, make a long and looping pilgrimage from Texas into Mexico, where they find work at a ranch. This being McCarthy, the adventure is leavened with complications and tragedy. Yet unlike his earlier novels, “All the Pretty Horses” offers a whisper of redemption — or maybe deliverance is a better word. Winner of a National Book Award, it marks a return — and a largely successful one — to a stripped-down style.

“The Crossing” (1994)

The second volume of the trilogy is only thematically connected to the first. Gone (for the moment) are Cole and Rawlins, replaced by another pair of young cowboys: Billy Parham and his brother Boyd. The book is built around three crossings from New Mexico into Mexico, and as in “All the Pretty Horses,” the writing is spare, if not exactly minimalist. The key shift here is to a tone laden with longing, even regret. At the same time, it cycles and builds to a resolution, making this among the most accessible of the author’s works. And, yes, it can be read as a stand-alone.

“Cities of the Plain” (1998)

The final volume of the “Border Trilogy” brings Cole and Parham together for an odyssey that is both departure and return. Beginning in 1952 on a New Mexico cattle ranch, the novel recalls some of the violence and desperation of the Southern novels, revolving as it does around Cole’s doomed infatuation with a prostitute in Juarez. There is death here, a lot of death, and retribution, and also sacrifice. “Our decisions,” McCarthy writes, “do not have some alternative. We may contemplate a choice, but we pursue one path only.”

Bethanne Patrick’s December standout books include a Gen X caper, a wild adventure tale and surprising new novels from Jane Smiley and Cormac McCarthy.

The late period

“No Country for Old Men” (2005)

It may seem a stretch to separate this novel from the Western books of McCarthy’s mid-career; it too takes place in the border region. But it represents another shift — into more highly plotted narrative. This is a crime novel, or McCarthy’s version of one, but although I admire the language and some of the scenes, the narrative suffers from a lack of ambition. For all the bloodshed, there isn’t enough weight or meaning for this to register as one of McCarthy’s major works.

“The Road” (2006)

McCarthy won a Pulitzer Prize for this novel, which renders the author’s apocalyptic tendencies explicit in a story about a father and a son traversing a kind of “Mad Max” America after an environmental tragedy. It’s an unlikely turn for McCarthy, almost into the realm of science fiction, but even more unexpected are the book’s touches of tenderness. I go back and forth on this novel; in many places, it seems too simplistic, almost like a parable. But the whisper of hope (or at least continuity) on which it ends is as vivid as it is unforeseen.

“The Passenger” (2022)

McCarthy’s first novel in 16 years begins as a salvage diver named Bobby Western explores a private jet that crashed off the Gulf Coast, and from which a passenger has mysteriously disappeared. Quickly, however, McCarthy pivots from that mystery to those of quantum mechanics and the workings of the universe. This is a talky piece of fiction, featuring long narratives about Vietnam and the Kennedy assassination and theoretical physics; it is riveting in places, but it also has a lot of loose ends. And why not? In many ways it relies on its companion volume, “Stella Maris,” to resolve (or attempt to resolve) its narrative.

“Stella Maris” (2022)

Structured as a series of (Socratic?) dialogues between Bobby’s sister Alicia and a therapist at the institution she has checked herself into, this is a leaner work than “The Passenger,” a deep dive into psychological dysfunction and a further inquiry into the mechanics of existence — inasmuch as that can be understood. I found it thrilling, a novel in which almost nothing happens, or has to happen, since we know from “The Passenger” how everything will end.

…

If you want to know what I think, I lean toward the early McCarthy: the Southern novels, “Blood Meridian.” But there is something memorable in every book: ideas and sentences and odd plot turns, strange beings occupying a dark and inexplicable world. Does that world end in apocalypse? Most likely — for human beings, at any rate. The power of McCarthy’s fiction is that he has always understood this; he’s just waiting for us to come around.

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.