Review: Bob Dylan’s new book is revealing, misogynistic and a special kind of bonkers

On the Shelf

The Philosophy of Modern Song

By Bob Dylan

Simon & Schuster: 352 pages, $45

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

What should we make of the title of Bob Dylan’s new book? “The Philosophy of Modern Song” is a mouthful, a phrase that puts on airs. It asserts that the book is an important work, a tome that merits a place on your loftiest library shelf, up in the thin air where you keep the leather-bound, gilt-edged stuff. It has a list price worthy of an opus, $45 — pretty steep for a volume that pads out more than one-third of its pages with, per the Simon & Schuster press release, “carefully curated photographs.”

But the title is also a wisecrack, too puffed up and self-important to be taken at face value. For decades, Dylan has been laying boobytraps for his devotees, the Dylanologists who rake through his songs and scraps, seeking clues to the Riddle of Bob. The book title feels like a joke at their expense, and, maybe, a jibe at the pointy-heads in Stockholm who awarded him the 2016 Nobel Prize in literature.

In any case, “philosophy” is a useful term, vague and baggy enough to accommodate the mix of music criticism, beat poetry, wolverine snarls and Lear-on-the-heath tirades that comprise the book’s 66 chapters about 66 songs. Readers of Dylan have encountered writing in this vein before. There is the meditation on the Brecht-Weill song “Pirate Jenny” in his 2004 memoir “Chronicles: Volume One,” and the music-themed reveries scattered through his mid-’60s prose-poetry experiment “Tarantula.” The closest model may be the monologues Dylan delivered on “Theme Time Radio Hour,” the Sirius XM show he hosted from 2006 to 2009. But “The Philosophy of Modern Song” has its own wild flavor. It is — for better and, alas, worse — a special kind of bonkers.

It isn’t a book that takes time to clear its throat. Dylan offers no introduction or contextualizing chit-chat, hot-rodding straight into an essay about “Detroit City,” a 1963 hit by country singer Bobby Bare. “In this song you’re the Prodigal Son,” he writes. That second person pronoun is noteworthy, a key to the author’s ideas — his philosophy, if you insist — about how songs work. “Knowing a singer’s life story doesn’t particularly help your understanding of a song,” Dylan writes. “It’s what a song makes you feel about your own life that’s important.”

Tuesday’s performance felt like a gift: a thoroughly engrossing outpouring of roots music and folk-soul balladry, with Dylan in richly expressive voice.

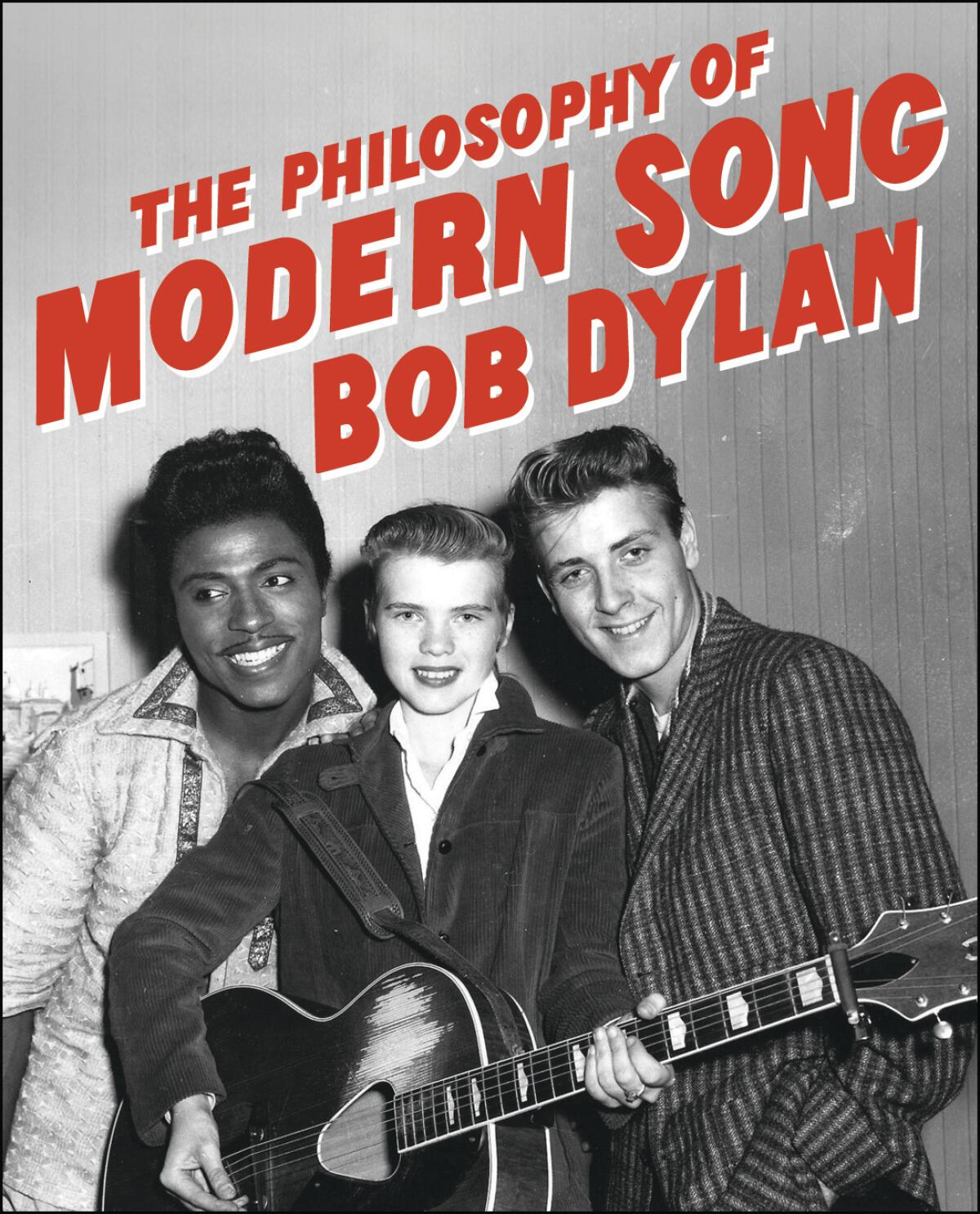

That formulation could be turned in a different direction: If you know a guy’s favorite songs, you gain understanding of his life. Dylan’s playlist in “The Philosophy of Modern Song” isn’t exactly surprising, but it is revealing. There is a lot of blues and country. There’s some soul — Ray Charles, Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes — and several songs by the titans of early rock & roll, including Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins and Little Richard, Dylan’s hero in his teenage years. Most of us fall hard for pop music as adolescents and never quite shake the stranglehold those formative hits have on our consciousness. Dylan is no different. Twenty-eight songs in the book date from the 1950s. Nine were released in 1956, the year Dylan turned 15.

He also writes about ‘60s and ‘70s rock anthems — the Who’s “My Generation,” the Clash’s “London Calling” — and makes a couple of excursions into the ‘80s catalog of Willie Nelson. But it’s clear that Dylan’s definition of “modern song” does not extend into the hip-hop era. He mentions Run-DMC, the Notorious B.I.G. and Jay-Z but doesn’t delve into the music. The most recent recording he considers, from 2004, is a rendition of a Stephen Foster song that was composed in 1849.

Some of the book’s most passionate passages concern the songbook of Dylan’s parents’ generation, hits crooned by the vocal stars of the pre-rock era. Dylan did as much as anybody to dislodge that music from the center of American life, but in the last two decades he has reclaimed and recontextualized it. On albums like “Love and Theft” (2001), “Modern Times” (2006) and his recent sequence of Sinatra tribute records, Dylan sounds like a grizzled version of a ‘30s balladeer. Those recordings make a case against folk purism, arguing that the old pop standards are as powerful and mysterious any as any field holler or singer-songwriter’s confession. In a chapter about Perry Como’s 1951 recording of the Tin Pan Alley warhorse “Without a Song,” Dylan hails Como, often dismissed as milquetoast, and champions musical interpretation over auteurism: “Perry Como lived in every moment of every song he sang. He didn’t have to write a song to do it. … What more could you want from an artist?”

As a work of prose, “The Philosophy of Modern Song” is relentless. It rip-snorts along, charging from song to song, idea to idea. Dylan can write what journalists call a great lede: a first sentence that detonates like a hand grenade. “This song speaks New Speak.” “This song is the grinning skull.” “In this song the fire’s gone out and your life is missing.” Sometimes, he renders straightforward judgments, weighing the beauty of “Blue Moon” with its “melody right out of Debussy” or exulting in Hank Williams’ “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” a song that is “perfectly played and sung … with the exact correct intensity.” Hints of professional rivalry and one-upmanship creep in. In a chapter on Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up,” Dylan correctly notes the song’s debt to his own “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and delivers a sly double-diss, aimed at Costello and another rock star: “At the point of ‘Pump It Up,’ [Costello] obviously had been listening to Springsteen too much.”

Bob Dylan opened the doors of what was possible in popular music with his 1965 single “Like a Rolling Stone,” a 6-minute epic built on four poetically surrealistic verses linked by the emotionally liberating “How does it feel?”

More often, though, Dylan is in a different dimension altogether, cruising the space-scape of his imagination. For Dylan, songs aren’t just artworks to be analyzed and explicated; they’re visions that beget visions, prompts for his own madcap and macabre yarn-spinning. His essay on the Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion” paints scenes of societal collapse: “Blood running in the streets, earthquakes on the next block, women getting raped on the corner, spaceships taking off. Nothing fastened down.” The entry on Uncle Dave Macon’s “Keep My Skillet Good and Greasy” (1924) is an extended culinary riff, a metaphor that keeps mutating until it’s ordered everything on the menu:

“You’re Long John Silver and you’ve got snakes in your boots, fortune cookies and glazed donuts, and you’re drinking iced coffee — eating dried beef and picnic ham, swallowing whole mouthfuls of Boston cream pie. … This song melts everything down, browns it up and deep fries it — it’ll milk the cow till it gives blood.”

What does all this add up to? Not quite a philosophy of modern song, or at least not a coherent one. But coherence isn’t what you want from Bob Dylan. What you want is to watch songs ping-pong around his brain; you want a close encounter with his mind. Unfortunately, that same mind is the storehouse for some extremely dark and disturbing ideas about — to use the retrograde term that Dylan himself employs — the opposite sex.

You have to plow through 46 chapters before encountering a song by a female artist. (Cher’s “Gypsies, Tramps & Thieves.”) There are only four songs by women in the book. That’s Dylan’s prerogative, of course; he’s writing about his record collection, not mine or yours. Yet women loom large in his consciousness and are omnipresent in his pages — appearing in such monstrous form, evoked in language so marinated in misogyny, that, reading “The Philosophy of Modern Song,” I began to feel like a therapist, sneaking glances at my watch while the crackpot on the couch blurts one creepy fantasy after another.

The women we meet in Dylan’s essays include a “she goat,” a “crazy bitch,” a “gold digging showgirl, full skirted in a cocktail dress” and a “hot-blooded sex starved wench.” Dylan describes women as “pug-nosed, grim faced and short on looks,” “bare breasted, blue veined — short, powerful, and ugly” and “foul-tasting.” Sometimes Dylan sounds like a garden-variety sexist jerk. (“Her voice gets on your nerves — the low drone, the squeaking sounds.”) But he also spews bile from the murkiest depths of the male id. He refers to the labia majora as a “steel trap.” He writes of a woman who “feeds on the entrails of your victims, and if you pull back her skin, you’ll see the head of an animal.”

Well, Shakespeare, he’s in the alley Speaking to some French girl Who says she knows me well He was the kid on the coffee house stage growling out songs from behind a guitar that seemed to weigh more than he did.

Dylan’s essay on the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman” occasions a rant about “The woman from the global village of nowhere — destroyer of cultures, traditions, identities, and deities.” Elsewhere he gives voice to what can only be called a psychosexual murder fantasy: “You want to maim and mangle her. You want to see her in agony, and you want to blow this whole thing up until it’s swollen, where you’ll run your hands all over and squeeze it till it collapses.”

Then there’s the chapter on Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her,” a funny soul-blues song about divorce that sends Dylan into a diatribe about polygamy: “It’s nobody’s business how many wives a man has. … But the screws already get tightened from all sides — women’s rights crusaders and women’s lib lobbyists take turns putting man back on his heels until he is pinned behind the eight ball dodging the shrapnel from the glass ceiling. … What downtrodden woman with no future, battered around by the whims of a cruel society, wouldn’t be better off as one of a rich man’s wives — taken care of properly, rather than friendless on the street depending on government stamps?”

It’s a bummer, to put it mildly, to find a Nobel laureate — and, more to the point, the writer of “Tangled up in Blue” — mixing metaphors and spouting nonsense like an elderly uncle who bulk-emails links to Fox News segments. In one of “The Philosophy of Modern Song’s” pithier moments, Dylan makes the obvious but important point that pop lyrics, which may “seem so slight” when read, are “written for the ear and not for the eye.” It’s when those words are set to music and dramatized by a singer of skill and sympathy that the magical transmutation occurs.

Dylan is a brilliant songwriter, of course; the truth is, he’s a better singer, a master vocal stylist whose performances speak to the deeps of human emotion even when they carry unseemly attitudes and ideas. But when his words just sit there, between hardcovers on a stark white page, their discordant notes are hard to bear.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.