How Barbara Kingsolver makes literature topical — from climate change to opioids

On the Shelf

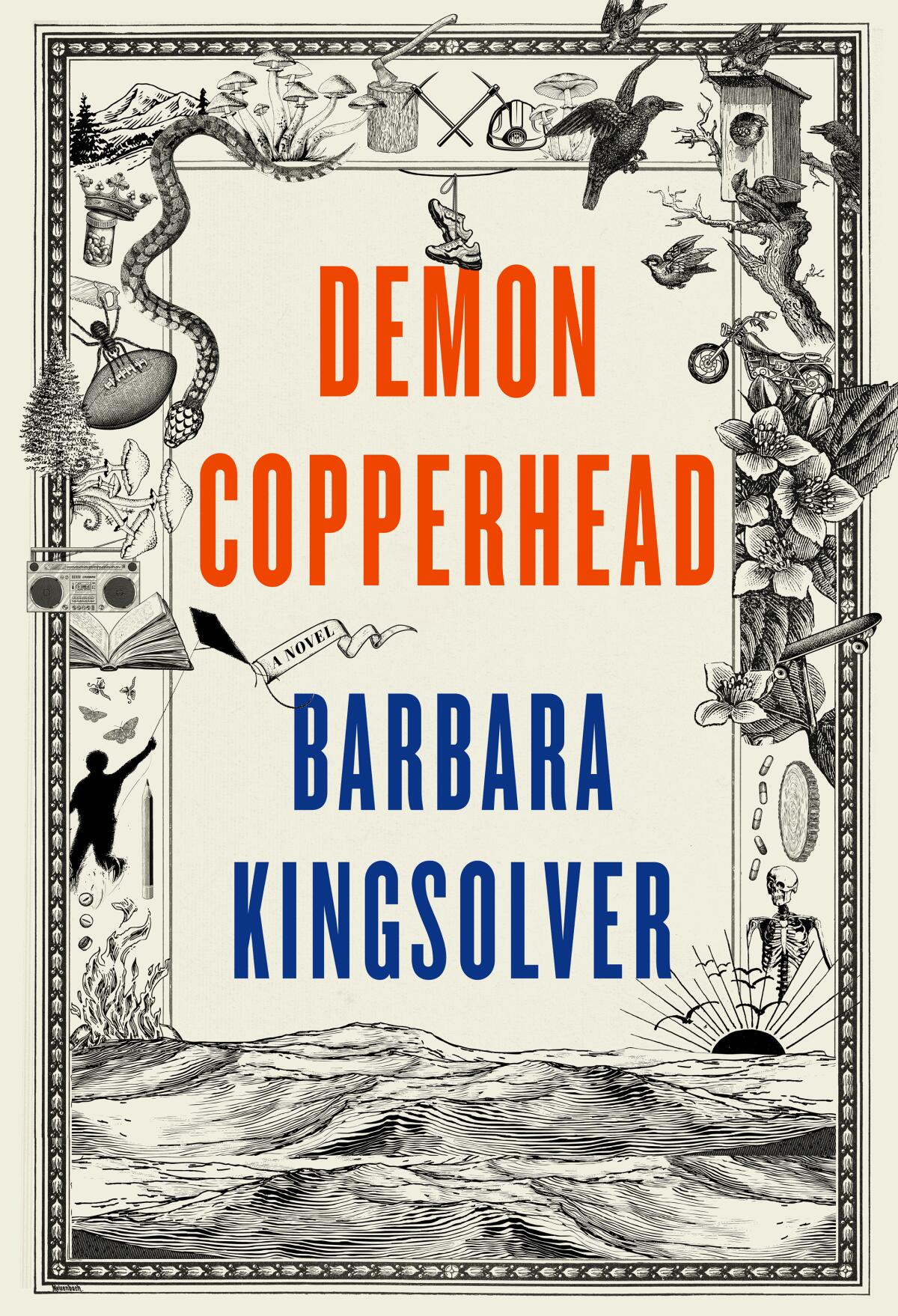

Demon Copperhead

By Barbara Kingsolver

Harper: 560 pages, $33

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In 1988, a friend passed me her tub-bubbled copy of Barbara Kingsolver’s first novel, “The Bean Trees.” The book had me at Line 1. “I have been afraid of putting air in a tire,” Kingsolver wrote, “ever since I saw a tractor tire blow up and throw Newt Hardbine’s father over the top of the Standard Oil sign.”

“The Bean Trees” was a surprise hit, clearing a path for its author, then 34, to spend the next three decades racking up bestsellers, melding elegantly crafted, straightforward prose with complex characters, politics and plots. Her 1998 novel “The Poisonwood Bible” was an Oprah Book Club pick and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. Founder and funder of the Bellwether Prize for Socially Engaged Fiction, Kingsolver has also authored two books each of essays and poetry and three nonfiction works.

A former biologist raised in Kentucky, Kingsolver tends to bind her writing to the dirt beneath her feet. During her years living in Tucson, her palette was the red Southwest soil. Since moving in 2004 to southern Virginia, she has set two books there: “ Animal, Vegetable, Miracle,” a polemical account of her family’s year as locavore farmers; and now, “ Demon Copperhead,” a contemporary reimagining of Dickens’ “David Copperfield.” On Tuesday it was made an Oprah pick as well.

As usual, Kingsolver’s 10th novel gives voice to her political positions — in this case, Big Pharma’s opioid assault on Appalachians. “Copperhead” is a compelling exposé of the twisted cruelties that make Kingsolver’s real-life neighbors susceptible to addiction’s grip: abject poverty, the broken social services and public school systems, the agricultural-industrial complex, “hillbilly” stereotyping and the devaluation of human skills other than football (boys) and “putting out” (girls). Layered and multidimensional, her characters’ quirks and strivings shine a light on the wrongs that wound and thwart them.

The novel’s protagonist is the redheaded, artistically gifted, stunningly resilient Damon, a.k.a Demon, born in a trailer to a teenager whose addiction quickly overtakes her capacity to provide maternal care. From Kingsolver’s trademark gut-punch of a first sentence — “First, I got myself born” — we follow Damon through 560 pages of what “growing up” looks like for a kid whose external resources amount to less than zero.

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

Because she cares about a lot of things, Kingsolver knows about a lot of things. “Demon Copperhead” is a character-driven novel, its narrative arc convoluted by more ruts and potholes and switchbacks than a country road. Yet the book is also packed with so much information that Kingsolver could have shifted her lens from people to problems and called it journalism instead. Consumer warning: If you don’t want to trade in your beliefs for the truth about Appalachia and its people, avoid this book.

But if you agree with Kingsolver’s devoted fans, including me, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, which awarded Kingsolver our nation’s highest honor for service through the arts, our email conversation — edited for length and clarity — is for you.

There’s really nothing like being immersed in a Kingsolver novel. Do you have a secret method for sucking the reader into the vortex of your imagination?

My secret is boring: I spend thousands of hours with my hands on a keyboard. At the end of a first draft, I go back and write it all again, and again, with a better sense each time of where I’m headed. I read it all aloud to myself. Every sentence gets revised until it feels perfect to me, even if that takes 50 tries. The ridiculous thing is, I love every minute of this. I love the characters, the world-building and that huge, heady feeling of bringing home an ending as if I’m landing an aircraft. Maybe that’s the secret to any success: to chase a vocation you can embrace so hard, you’ll give it your absolute everything. And feel lucky to do it.

What comes first when you’re creating a novel? The social issues? The characters? The plot?

My novels always start the same way: with a question. It needs to be a big question — worrisome, complicated, relevant to our times — because look, I’m asking you to put down your life for a while and hear me out. I devise a plot that will make this question manifest and invent all the characters I need to serve my plot.

What was the big question behind “Demon Copperhead”?

Right now we need to talk about the opioid epidemic, a calculated exploit by Purdue Pharma that has left us with a generation of damaged and orphaned kids. How did this plague of prescription drug abuse come here, what made us vulnerable, how is it connected with history, how have Appalachian people been kept poor on purpose? Huge questions, no easy answers. My job is to make sure you enjoy the time we spend walking around in there, watching lives, listening to creative language, seeing things from fresh angles. That’s what literature can do.

At 80, the author of “The World According to Garp” and so much more talks about his longest and Irving-est book yet, “The Last Chairlift.”

How did you build your plot and characters to serve that driving question?

I spent years looking for a way into this story that could get past hillbilly-drug-user prejudices and dig into a deeper emotional landscape. The solution came to me via Charles Dickens. Orphaned kids and institutional poverty were totally his wheelhouse. “David Copperfield” is so grim. How did he pull it off? Through the urgent, unbearable truth-telling of the child himself. I decided to let that kid tell the story: David Copperfield, my version, nicknamed Copperhead because he’s a redhead and slightly dangerous. His funny, pissed-off voice came alive in my ear and refused to shut up until I gave him his due.

Damon strikes me as your bravest, most ambitious creation yet. How did your life in Appalachia impact his character?

This novel exists because I’m Appalachian and fed up with the way mainstream media portray us as dumb jokes or objects of pity. (If we show up at all.) I’m committed to honest representation of the beauty and complexity of this place.

Were you concerned that your characterization of the addicts in the novel might contribute to stereotypes about Appalachians?

The bedrock of Appalachia is community, and my portrait of it is a complex ecosystem of roles and personalities: Even the addicted teen mom is more nuanced than a stereotype, as I hope readers will see. This story has philosophers, narcissists, caretakers, opportunists, teachers and artists of many kinds. We’re some of everything in Appalachia. We have startling geniuses and sadly damaged brains. If I had to generalize, I would say we’re just shorter on resources than people in other regions — and longer on resourcefulness.

Violence: When our presidents and film heroes solve problems by killing people, what do we expect from our children?

Do you consider the marketability of a book as you’re conceiving it?

I don’t really worry about being marketable, but I think every minute about staying accessible. Characters have to be as vivid as your own friends. Scenes have to be visible to your mind’s eye. Plot has to be like gravity, a constant, pulling on you to turn every page. And since ebook readers can sample before they buy, I’ve got to get all this done in the first 30 pages. Now, even a novel has to elevator-pitch itself!

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.