George Saunders’ saintly, disappointing new stories: A tender-hearted takedown

On the Shelf

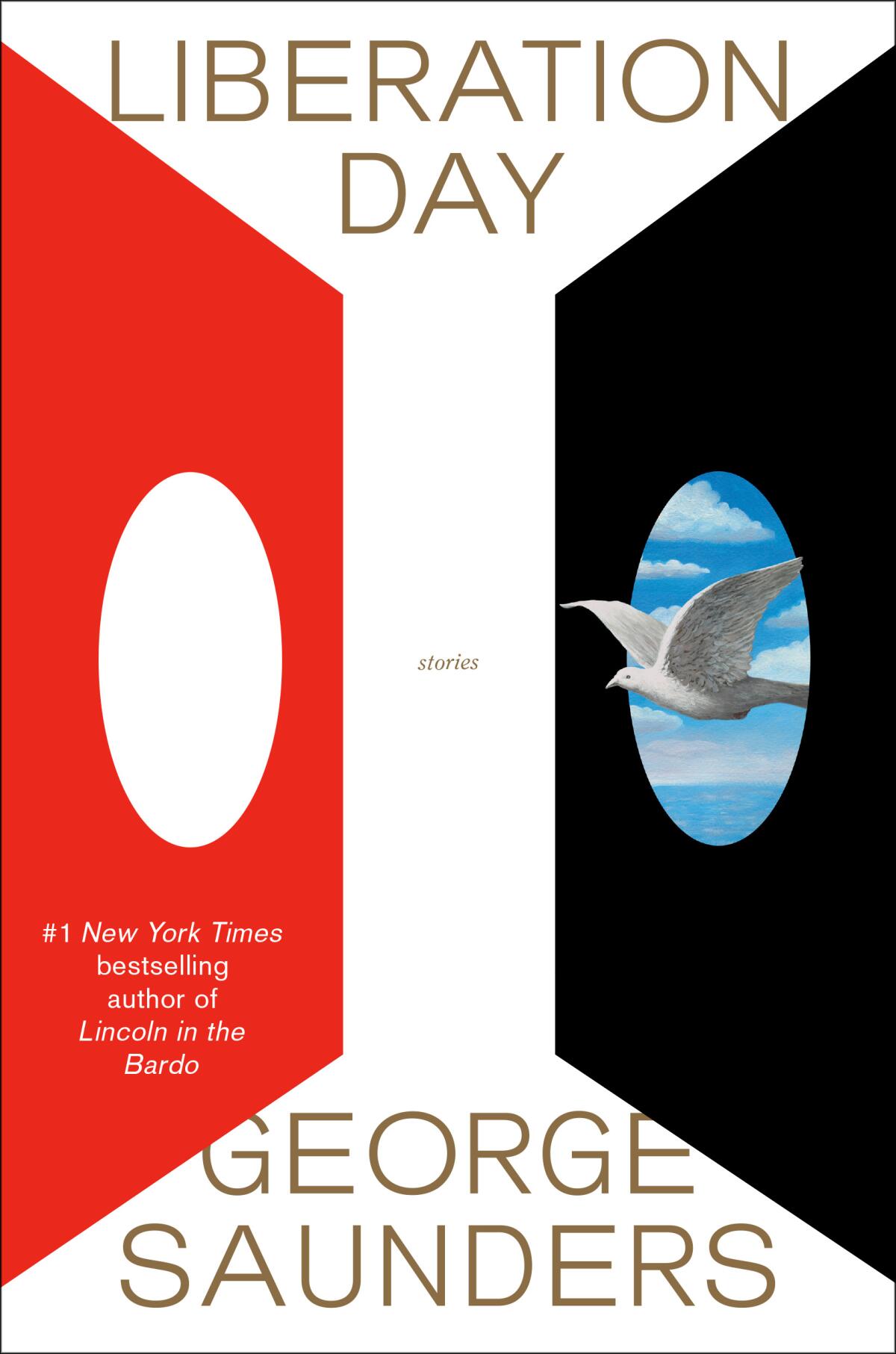

Liberation Day: Stories

By George Saunders

Random House: 256 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Every saint is guilty until proved innocent, George Orwell said. This is bad news for George Saunders, who’s probably as close to a living candidate for canonization as American literature has. Saunders is not just a major author in the eyes of both critics and readers — his sole novel, “Lincoln in the Bardo,” appeared at No.1 on the New York Times bestseller list, James Patterson territory — but a revered creative writing teacher at Syracuse University, the deliverer of a brilliant and slightly annoying viral commencement speech about kindness and a practicing Buddhist.

How to take up arms against this array of virtues! A scathing review would be the easiest way. Let’s see what we can do.

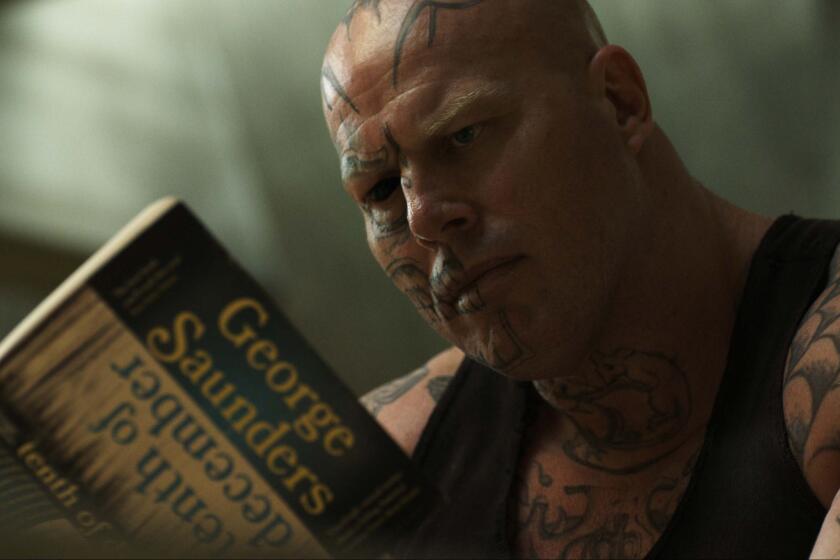

The book that vaulted Saunders to widespread fame was his marvelous 2013 story collection “Tenth of December.” In it, he seemed to shove fiction abruptly in the direction of the 21st century, describing humans as they muddled through overwhelming modernities. The stories were not just smart and wise but funny, that rarest quality in short fiction. He followed it with “Lincoln in the Bardo,” about Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the heaviest fighting of the Civil War, mourning his son in a graveyard full of antic, loudmouth ghosts. It won the Booker Prize. Now he’s published a new collection of stories, “Liberation Day.”

Saunders often begins in media res, disorienting us with strange language that resolves, eventually, into a rueful clarity. (My suspicion is that the technique derives from fantasy novels — whether that’s true or not, these confusions were another way in which “Tenth of December” so successfully mimicked the feeling of being alive after the turn of the millennium.)

If anyone can teach you writing, maybe George Saunders can?

And so it may actually feel familiar to Saunders readers when, a few lines into the new book’s title story and opener, the narrator blithely says, “One may be unPinioned before the eyes of the upset others and brought to a rather Penalty area. (Here at the Untermeyers’, a shed in the yard.)” That combination — baffling futuristic lingo punctuated by the prosaic fact of a backyard shed — is quintessential Saunders.

As the story, nearly a novella by length, continues, Saunders hits many of his old marks, invoking Custer, the ethics of AI, the shambling myopia of the adult children of the rich, the varieties of acting all of us perform. There’s surprising violence and, in the character of an unloved housewife who seeks comfort from one of the (“Pinioned”) creatures, unexpected pathos. There is also a close examination of two of the author’s most consistent themes: freedom vs. confinement and moral hazard. In other words, “Liberation Day” picks up where “Tenth of December” left us.

But the settings on the supercollider feel just off this time. The standard of Saunders’ writing remains astronomically high, but there are slippages suddenly. In the title story, for instance, the narrator combines the orotund diction of a robot with little comets of slang, “super nice,” “killing it,” in a way more manufactured than anything in “Tenth of December.” “What is great?” he asks later. “That is what my heart longs to ask. What is lush? What is bold, what is daring? In which direction lies maximum richness, abundance, delight?” It’s a fine piece of writing, but in context it seems detached from the narration, as if the author’s moral preoccupations have begun to precede his writerly concerns.

Perhaps Saunders is in part the victim of his own influence; all of the previously published stories here appeared in the New Yorker, and sometimes they feel like every New Yorker story does now: confident, current, sad. And it’s worth restating that even a bad Saunders story is good in so many ways: All nine in this ultra-readable book contain pulses of wit and beauty, superb unexpected lines, sudden laughs.

The new movie “Spiderhead,” starring Chris Hemsworth and Miles Teller, distorts a great George Saunders story into an empty good-versus-evil tale.

Indeed, in two of them, “Mother’s Day” and “A Thing At Work,” he reaches the heights of his previous fiction. The best in the collection is the former, about two terrible, self-justifying mothers mentally attacking each other from across the street (“Did she just get to live out her life, mean as all get-out?”) before a hailstorm offers them a chance at redemption. Like Roberto Bolaño and Alice Munro, two other masters of the form, Saunders loves the short story’s capacity to dilate time, to show the young bride as an old woman full of knowledge won by loss. What if your choices were wrong? What if you’re not exactly the victim you thought you were? He is unsurpassed at leaving these kinds of questions in the reader’s mind.

But the rest of “Liberation Day” is less powerful, as if the convulsive quality that makes art great has diminished. Instead, there are a great deal of tender and extremely well-written passages about how hard life is. And of course, life is hard, horrifying and hard, and Saunders is justified in continually pursuing that subject to its roots. It turns out, I think, that the saintliness is real. “I want to meet the heart that breaks halfway around the world,” as Simone de Beauvoir said of Simone Weil.

What’s fallen off a little is the stories freighting that message. The trouble is that morality and art famously have nothing to do with each other. As in his earlier work, Saunders’ relentlessly humane vision of life, always in comic search of our deepest negations of each other, is remarkably vivid. But his innovations as an artist have waned into repetitions; and genius is an erratic visitor.

Finch’s novels include the Charles Lenox mysteries.

The latest from Ling Ma, Yiyun Li, Russell Banks and Namwali Serpell as well as exciting newcomers round out our critics’ most anticipated fall books.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.