Review: The road to California’s energy disaster: A new history of PG&E paints a bleak picture

On the Shelf

California Burning: The Fall of Pacific Gas and Electric — and What It Means for America's Power Grid

By Katherine Blunt

Portfolio: 368 pages, $29

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When I read Pacific Gas and Electric’s mission statement aloud to my wife, her eyes narrowed.

“We are delivering for our hometowns, serving our planet and leading with love,” I recited.

Her response: “Forget the love. How about you try not to burn my house down?”

PG&E is trying. After decades of gross negligence, multiple wildfires, a neighborhood gas pipeline explosion, scores of guilty pleas to involuntary manslaughter and billions in property damage, the company appears at last to be taking safety seriously. Its efforts include a massive expansion of tree-trimming to protect power lines, plans to bury hundreds of miles of transmission and distribution lines underground and quick power shutoffs on the most dangerous hot and windy days.

None of it is enough to counter the company’s long-held reputation as an arrogant, sloppily managed corporation that cares more about stock price than safety.

Wall Street Journal reporter Katherine Blunt tells us how the company got that way in “California Burning: The Fall of Pacific Gas and Electric — and What It Means for America’s Power Grid.”

For years, PG&E produced returns for investors by cutting safety measures, increasing the risk of setting fires. That cost incentive still exists.

She begins with the spark that exploded into the Camp fire, the blaze that swept through the town of Paradise in 2018, the most destructive fire in California history — thus far. It killed at least 85 people, with damage estimated at more than $16 billion.

An ancient, worn hook on a century-old PG&E transmission tower broke off and dropped onto a high-voltage wire, setting off a brush fire that spread through dry woodland and foothill towns over 150,000 acres.

Long story short: PG&E tried to engineer a culpability coverup, failed, was charged with crimes and declared itself bankrupt.

After opening with this defining crisis, Blunt offers a fascinating chapter on PG&E’s surprisingly colorful 117-year history, featuring stories of admirable pluck, including a winter sled race for water rights to build a power dam. The victor was the first to post his claim to a tree.

The story briskly moves to modern times, sketching out the state’s incompetent attempt at electric market deregulation at the turn of the new millennium. Politicians and regulators were played for chumps by Wall Street sharpies, and PG&E customers suffered rolling blackouts as the not-quite-free market failed to provide a reliable supply of electricity. “It was arguably one of the most complicated heists ever undertaken in California,” Blunt writes.

In more recent years, an even graver self-inflicted crisis has come to the fore. Climate change is not only a consequence of energy consumption but also a major threat to its infrastructure. As climate change contributes to the severity of Western wildfires, intense heat waves and cold snaps in Texas and hurricanes along our Eastern coasts, we are also facing a disruptive future that’s likely to include big rate hikes, electric power instability and physical danger.

As wildfires become more extreme, some worry California will near a tipping point in which its forests emit more carbon dioxide than they absorb.

Throw in war and inflation, and you have a crisis that can no longer be ignored or compartmentalized. For decades, consumer interest in gas and electric utilities has been limited to rate hikes (for most customers) and pollution and climate change (for environmental activists). Recently, a succession of energy crises, the latest in Europe, have made it clear that the future of the power grid — and reliable, affordable energy — is a burning question for everyone on the planet.

Blunt’s book is not a technical tome but a drama, a human tragedy, loaded with fascinating characters and tales of death and destruction, incompetence and chicanery, malfeasance and greed. Any detail necessary to understand the electric grid and how it works is woven seamlessly and clearly through the narrative.

PG&E, the giant utility that covers most of Northern California, takes center stage, but the supporting cast includes members of the state Legislature and the California Public Utilities Commission, which deserve more scrutiny than they’ve received for the roles they’ve played in PG&E’s conflagrations.

The safety problem, Blunt makes clear, is systemic. California likes to paint itself as an innovative leader, but its late-’90s move toward electricity market deregulation was a disaster.

The mishandling of the climate crisis was only one of its disastrous effects, albeit a crucial one. Blunt paints a picture — while in no way downplaying the need to address climate change — of long-term thinking that was ironically, tragically, short-sighted. Lawmakers and regulators, laser-focused on an aggressive transformation to cleaner energy, gave climate-change mitigation — in this case, wildfire prevention — short shrift. The author makes a good case as to why: Green energy is glamorous. Basic safety is not.

The next two months will bring anxiety, but also a handful of books on the crisis of fire, ranging from history to journalism to children’s lit.

The state’s policymakers “treated the company as a tool in their quest to preempt the long-term effects of climate change with ambitious renewable energy mandates,” Blunt writes. “In doing so, they failed to recognize that a changing climate had made PG&E’s power lines an immediate threat to the state.”

One big lesson learned: Because modern life is utterly dependent on massive inputs of electricity and other forms of energy, a laissez-faire market in large-scale power generation won’t work.

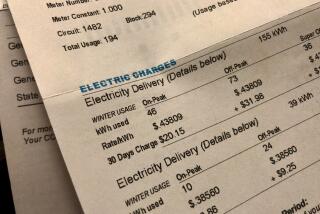

The biggest utilities in California will have to figure a way to earn a return for shareholders without compromising safety and reliability. This is true of the energy grid we have today, but especially urgent as the clean-energy transition accelerates (as often mandated by the government, which last week announced a full phaseout of gas-burning cars by 2035). While fixing today’s problems, PG&E and others will have to fix tomorrow’s — most foreseeably the challenge of keeping rates low enough to avoid a public backlash.

If past is prologue, it’s important to ask whether they’re up to the task. The residents of California might want to pay closer attention.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.