Salman Rushdie and the long shadow of ‘The Satanic Verses’

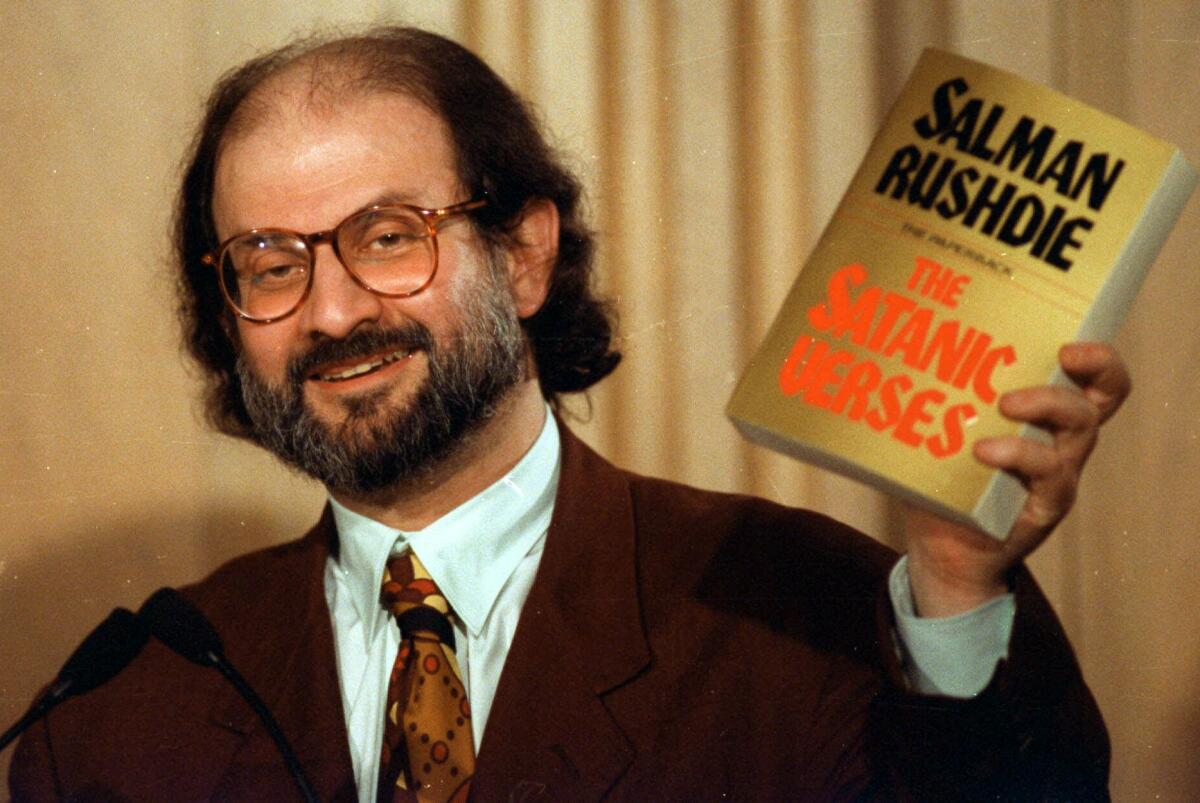

Salman Rushdie is the rare — the very rare — writer who is better known than his writing. Millions who know his name have never read his books — among them people who wanted to see him killed for writing one specific book, “The Satanic Verses.”

On Valentine’s Day 1989, the fundamentalist leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran delivered a fatwa, a religious decree, that called upon “all brave Muslims of the world” to “kill … without delay” the author of the 1988 novel, along with his editors and publishers, for the book’s “insult” to “the sacred beliefs of Muslims.”

Rushdie had anticipated some unpleasantness, and told an interviewer so years later: “I expected a few mullahs would be offended, call me names, and then I could defend myself in public.”

This, though, was a death decree, and Rushdie became a hunted man. The Japanese translator of his book was knifed to death. Another translator was attacked and wounded, as was the novel’s Norwegian publisher. Rushdie traveled with security protection, often under the name Joseph Anton, which he later used as the title of a book about that part of his life.

It was a life transformed, but it was still a life, magnified for his fellow writers and for the reading world by the knowledge that this was a man who might literally die for the words he had written.

And he nearly did when he was repeatedly stabbed during an Aug. 14 lecture in western New York, leaving him with a damaged liver, severed nerves in an arm and the prospect of losing an eye.

After the fatwa, his renown became elevated at a time when literary fame in general was on the wane — such that, for some turns of the news cycle, ordinary people, asked to name a famous writer, might have said ‘’Rushdie” the way they would answer “Einstein” to the same question about a scientist, or “Picasso” about a painter.

Rushdie was taken by helicopter to a hospital. “The news is not good,” his agent said, adding that he had nerve and liver damage.

I have interviewed Rushdie three or four times over something like 25 years. The first time, in the 1990s, the fatwa was still very much in force, so I was led to a safe house in Los Angeles, which turned out to be the home of a mutual acquaintance of Rushdie’s and mine. We agreed that was kind of amusing, as were the Mickey Mouse socks he was wearing.

Mickey is an unmistakable Western icon, and if there’s such a thing as divination by dress, I concluded that those socks made Mickey an expression of Rushdie’s personal insouciance, perhaps even defiance, in even the small things.

A few years thereafter, in 2001, Rushdie was lined up as a guest on my book interview program. As I recall, he was on tour for his novel “Fury,” about New York City. But 9/11, the 2001 terrorist attack by Islamist extremists, collaterally and paradoxically grounded Rushdie. Even after commercial flights started up again, Rushdie was for a time considered too high-risk a passenger to allow to board. He was his own one-man “no-fly” list — not for what he might do but for what others might do to him.

Rushdie has acquired an almost dual job description: as the author of works of literary fiction, not all of them critically acclaimed, and as a to-the-barricades standard-bearer for freedom of expression. Just as no book has as much power as a banned book, or a burned one — and “The Satanic Verses” lighted up plenty of bonfires — no writer has the moral authority of a writer with a price on his head, or a sword hanging over it.

With that came a dual scrutiny too: Is he up to that role? And writers asked themselves, Would I be?

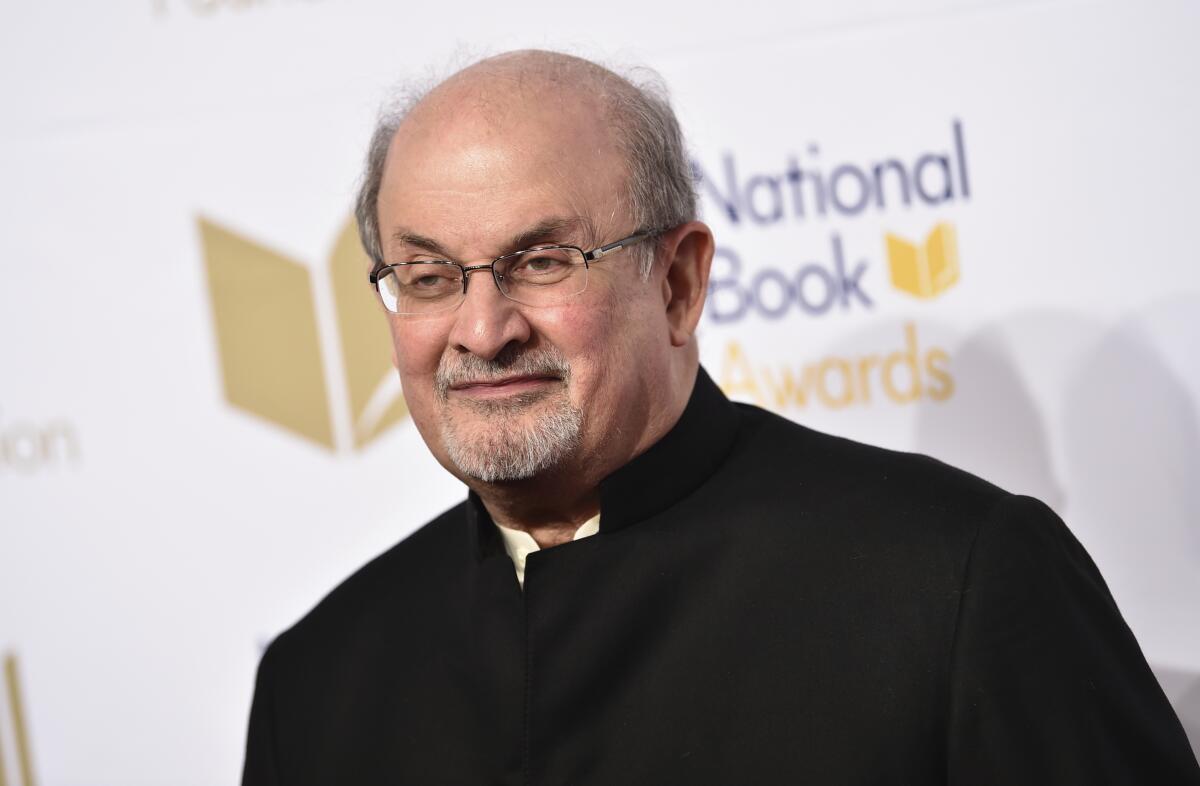

He acquired a résumé of distinction beyond book royalties and book reviews and the exalted Booker Prize: a past president of the writers’ group PEN America; a friend of Carrie Fisher; hanger-outer with Larry David; briefly husband to actress and author Padma Lakshmi; knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to literature.

Rushdie’s shining armor did not go undented. He and novelist John le Carré slung insults in print — Le Carré a “pompous ass,” Rushdie guilty of “self-canonization.” Both came to regret butting heads.

Rushdie was a celebrity even among celebrities, bringing the cachet of literature and heroics to the Vanity Fair Oscar party and other name-check events. There were snarky murmurings that he had caught “red-carpet fever,” relishing the acclaim that came with his stature as a writer under death sentence — a sentence we all seemed to be persuading ourselves had been commuted, though it wasn’t.

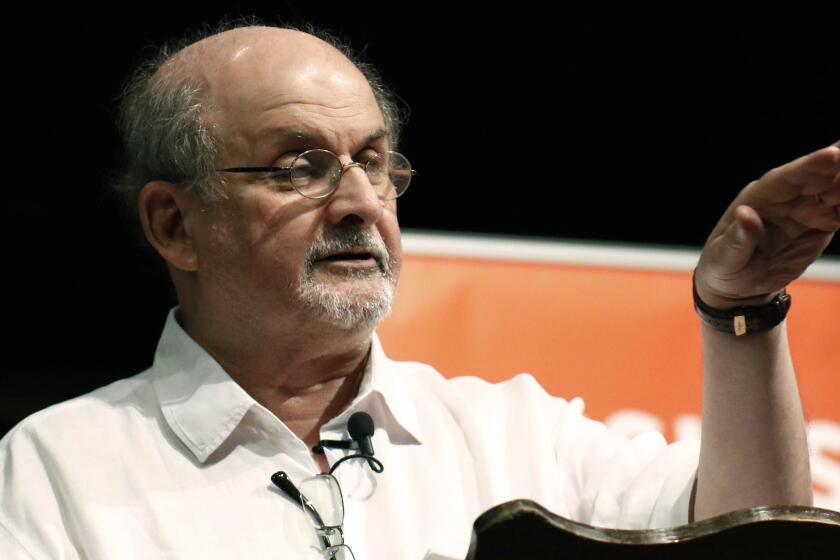

And then, a man leaped onstage at a literary gathering, knife furiously slashing, and reminded the world why Rushdie is more than an accomplished novelist. He epitomizes the very real relentlessness of tyranny. As forces of repression are determined to win debates by stopping debate, Rushdie — a bemused septuagenarian savaged by a knife and an equally vicious ideology — again makes us think, and not abstractly but in blood and pain, of all that is at stake in the world and in our own lives.

A fatwa was issued against Salman Rushdie in 1989 over his book ‘The Satanic Verses.’ But what is a fatwa and how has it affected his life and career?

President Joe Biden, whose White House may be trying to find a way back to a nuclear agreement with Iran, said a day later that Rushdie “stands for essential, universal ideals. Truth. Courage. Resilience. The ability to share ideas without fear. These are the building blocks of any free and open society.”

Over the weekend, “The Satanic Verses” hit No. 1 on Amazon, as people bought copies of the nearly 35-year-old novel to show solidarity with Rushdie and what he stands for.

What he stands for has always been clear, even when his critical reputation has been muddied. Rushdie was born into a nonpracticing Muslim family in India but is now an unswerving atheist. Asked at one point whether he is Muslim, he answered, “I am happy to say that I am not.”

His 1981 novel, “Midnight’s Children,” won the prestigious Booker Prize and sold a million copies in the United Kingdom alone. Wrought in the magical realism that infuses so many of Rushdie books, it takes as its inspiration the independence of India from Great Britain at the stroke of midnight, Aug. 15, 1947 — 75 years ago this week. The event also set in motion the partition of the subcontinent along religious borders dividing Pakistan and India.

From atop his dangerous platform, Rushdie has been consistent in demanding that we not flinch from critiquing and satirizing religion just to avoid offending believers. This, he believes, holds true for everyone, not just writers. Among his more famous remarks about religions in general: “‘Respect for religion’ has become a code phrase meaning ‘fear of religion.’ Religions, like all other ideas, deserve criticism, satire, and, yes, our fearless disrespect.”

The book title “The Satanic Verses” comes from a very old religious debate over historical suggestions that the prophet Muhammad was fallible — supposedly briefly tricked by Satan into endorsing some female pagan influences as part of his theology. This interpretation has been largely rejected as heresy by Muslim scholars for centuries, hence the furious reaction when Rushdie revived it as a literary device — in a manner one scholar called a “desacralizing treatment of the Koran.”

Novelist Salman Rushdie, who was attacked Friday, is the target of a decades-old fatwa by the late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Less than a year after the original fatwa, Rushdie tried to get some of the heat off himself. He publicly disavowed parts of “The Satanic Verses,” specifically statements “uttered by any of the characters who insults the prophet Muhammad, or casts aspersions upon Islam, or upon the authenticity of the holy Koran.” Islamic extremists didn’t buy into his walk-back; as recently as 2010 his name was reported to be on an Al Qaeda hit list.

In later years Rushdie called this recantation the “biggest mistake of my life.”

Thereafter, Rushdie spoke freely, and was about to speak for the umpteenth time when after 30 years the sword finally came down — an attack allegedly by a 24-year-old man who hadn’t even been born when the fatwa was decreed.

It happened at Chautauqua, an American institution that was founded as a college under canvas, a traveling tent roadshow taking an eclectic curriculum of learning, moralizing, culture and humor to heartland Americans as part of the better-citizens movement of the late 19th century.

Rushdie became a U.S. citizen in 2016, right ahead of the presidential election. I asked him about it in 2019, when we talked for my Times podcast and at Writers Bloc in Santa Monica. “I voted in it,” he said sardonically. “That went well.” We were discussing his latest book, “Quichotte,” starring a Quixote-in-a-Chevy Cruze — an American picaresque novel that spans opioids, reality TV and father-son relationships.

“I think there’s something of me in Quichotte,” he mused, “this kind of refusal to abandon hope, a refusal to give up on optimism.”

He never quite brought his Quichotte to the Los Angeles city line. The trouble with writing about L.A., he told me, is that big black-hole vortex known as the movies. “Everybody writes about movies, and everybody writes the same book about the movies. Years ago, there was a period I spent quite a lot of time here, and what I thought was that if you forget about Hollywood, this is a really interesting city.”

Yet there is something pop about Rushdie’s work, a gloss that completes the portrait of this modern Quixote whose battles with immovable objects can seem both reckless and fundamentally heroic. As dark as his novels can sometimes be, there is a silver thread of whimsy running through them, one that is brighter and broader in Rushdie the conversationalist. His sense of comic timing when he speaks to a live audience can be onstage-grade.

Patt Morrison talks with Salman Rushdie, the British Indian novelist and essayist.

When he speaks about censorship and menaces to unfettered expression, though, Rushdie delivers with deep-jawed bites like this one: “Free societies ... are societies in motion, and with motion comes tension, dissent, friction. Free people strike sparks, and those sparks are the best evidence of freedom’s existence.”

Nothing from his immense and resonant body of writing will likely be as often quoted, now or hereafter, as some of his remarks about freedom of expression, like this one:

“Nobody has the right to not be offended. That right doesn’t exist in any declaration I have ever read. If you are offended it is your problem, and frankly lots of things offend lots of people. I can walk into a bookshop and point out a number of books that I find very unattractive in what they say. But it doesn’t occur to me to burn the bookshop down. If you don’t like a book, read another book.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.