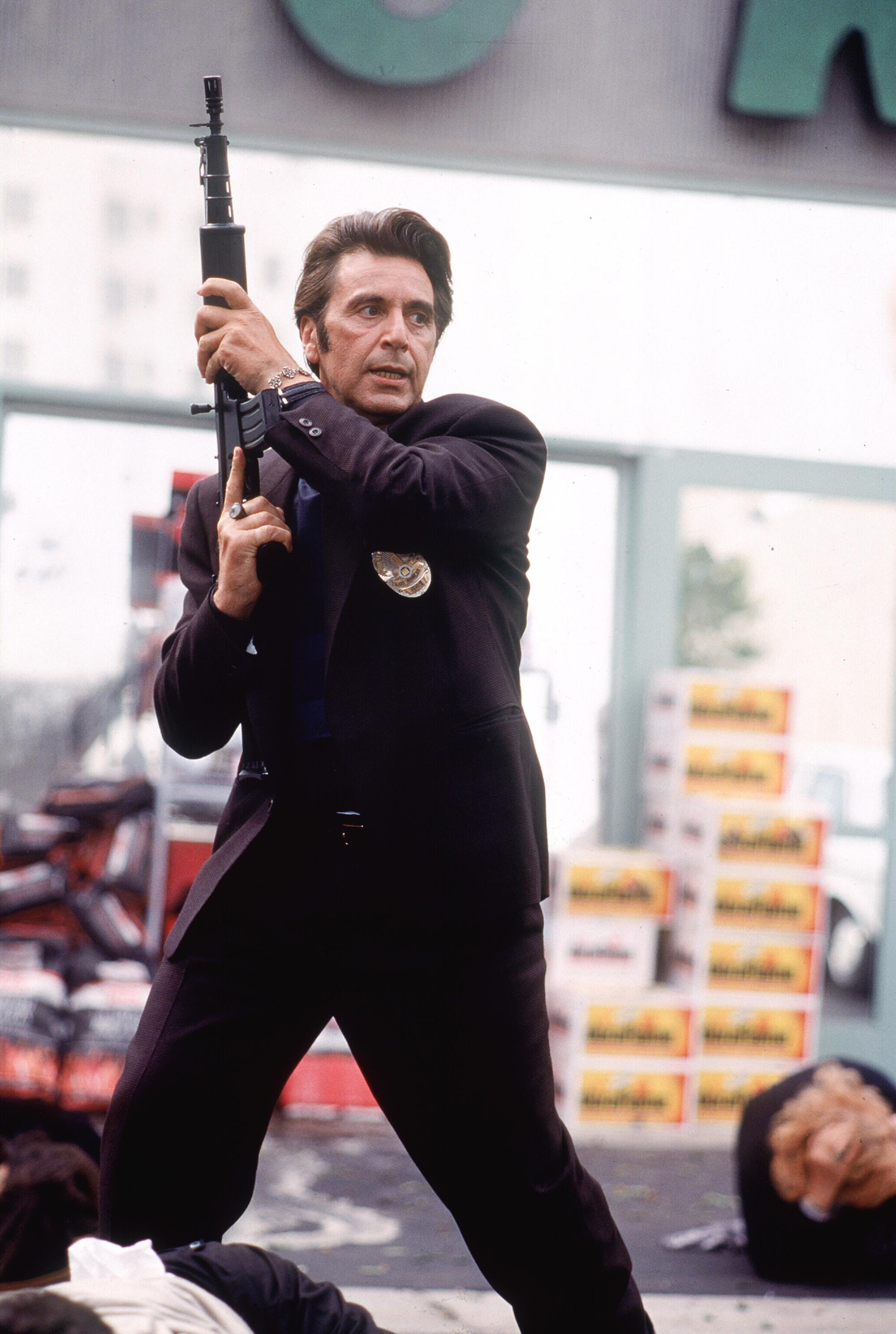

“Heat 2” is an odd sort of novel: a debut by filmmaker Michael Mann that happens to be a sequel to his 1995 film, “Heat.” But it does not, Mann insists, mark a return to the L.A. neo-noir classic that brought Al Pacino and Robert De Niro together onscreen for the first time. That’s because Mann never left it.

“Or it never left me,” he says on a Zoom call from Rome. “The material is so large, meaning what I knew and found fascinating about the origins and the potential futures of [De Niro’s criminal] Neil McCauley and [Pacino’s LAPD detective] Vincent Hanna is where they would go after the events of ‘Heat.’”

Chris Shiherlis, played by Val Kilmer in the movie, is the last man left alive the day after the film ends and the book begins. Wounded and desperate, he has to get out of L.A. “Heat 2” follows Shiherlis’ flight to Ciudad del Este in Paraguay. There he works security for the Taiwanese conglomerate behind a black-market software scheme. Employing a “The Godfather Part II”-like structure, the narrative intercuts his story with chapters set seven years earlier, in 1988, when McCauley’s crew attempts a daring takedown of a drug cartel in a Mexicali motel. Back in Chicago, Hanna is in pursuit of a home-invasion gang fond of rape and torture.

So why the novel? It took some persuasion from Mann’s wheeling-and-dealing agent, Shane Salerno of the Story Factory, to decide this was the best format for a sequel. One of the obvious logistical snags in the way of making a film: time. All the actors were older, no longer age-appropriate. A novel allows Mann to revisit the era and his characters unfettered by casting decisions — never mind the contortions and delays of the development process. Salerno negotiated an imprint for the filmmaker at HarperCollins, where two more books are under contract, perhaps including a second in the “Heat” universe.

Then it was time to find a co-writer. After a series of interviews, Mann selected Edgar Award-winning crime novelist Meg Gardiner, who shares his passion for the material and his dedication to research.

“Michael has amazing contacts everywhere in the world on all sides of law and order,” says Gardiner, whose novel “The Dark Corners of the Night” is being turned into an Amazon series. “It was an enlightening and extremely informative phone call we had for a couple of hours with a retired bank robber. Also an enlightening late night we did, riding out with two LAPD sergeants through some parts of Los Angeles to see what goes on after most businesses shut down.”

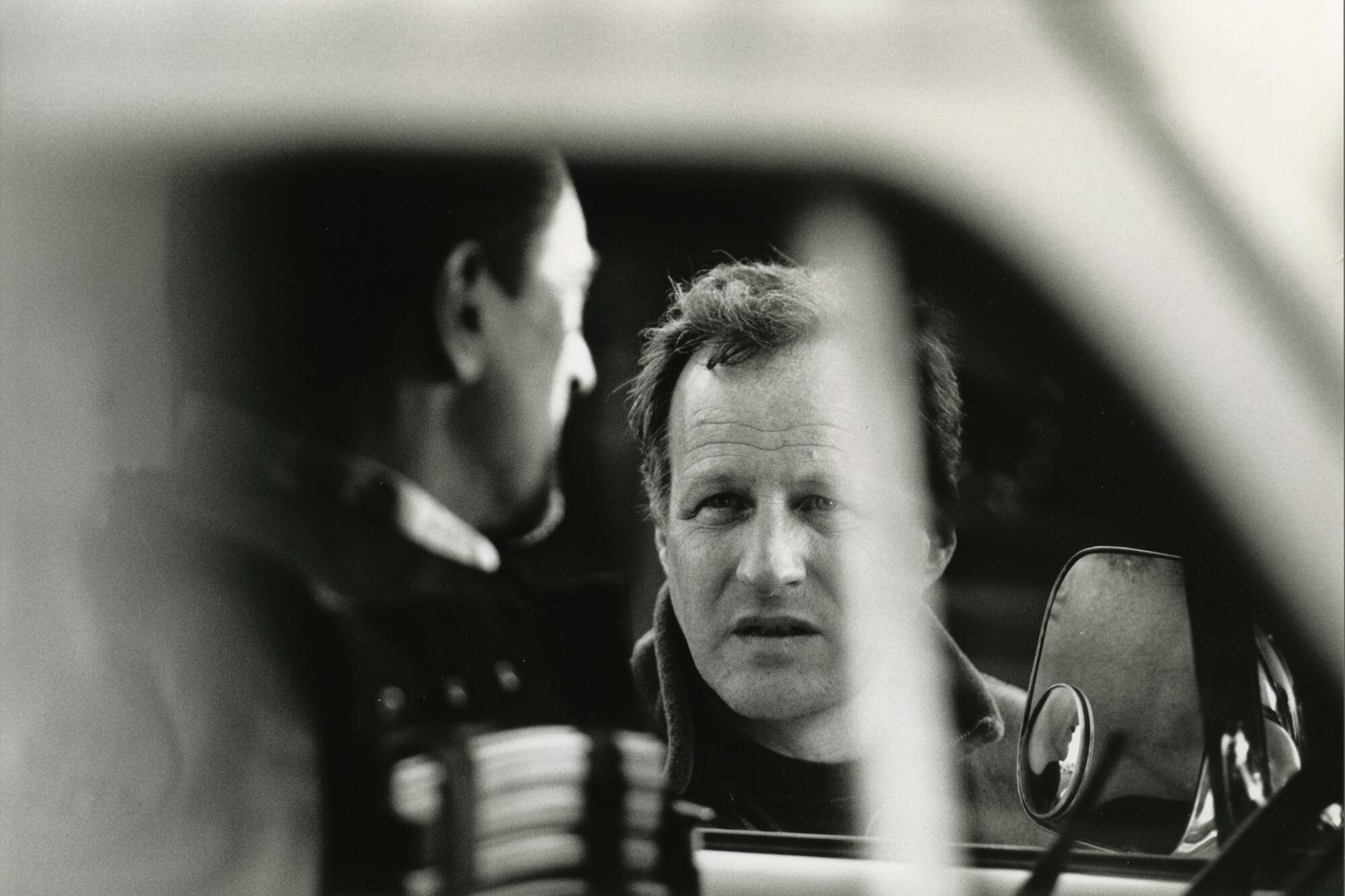

Michael Mann moves with purpose.

Working through the worst of the COVID-19 lockdowns, the pair traded chapters and notes for a year before finally meeting face to face. “Her powers of description are fantastic,” Mann says. “Before we started writing there was probably a 65-page narrative of what this novel would be. When people say story structure, that means work out every single beat of that story, and how all the parts are going to work together. ”

Like the movie, the book is concerned with cops and robbers functionally at the top of their game but existentially bottoming out. There’s a moment in the novel when Hanna, on his way home one night, his investigation floundering, suddenly finds himself on a highway headed south. On a deserted country road, he shuts off his headlights and floors it, suicidally hurtling through darkness. It’s a moment taken from Mann’s own youth.

“You just are driving through the city in the middle of the night. And you find yourself out in the black plains of Illinois heading down toward Kankakee, saying, ‘How long can I go if I turn off the light and I’m in the dark on this highway?’” he remembers asking himself. “I can’t see anything, and you just kind of dance with death, kind of a sick indulgence, but you do it. But I had no idea what I wanted to do and it was making me … crazy.”

Mann soon found some direction as an aspiring novelist at University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he earned his bachelor’s degree, followed by a master’s from London Film School. In Hollywood he found early success writing for TV shows before directing the TV prison movie “The Jericho Mile” in 1979. His feature debut came with 1981’s “Thief,” based on real-life criminal John Santucci — establishing a pattern of using real people as character inspiration.

“Santucci was a high-line pro jewel thief. He was a burglar. And I got very close to him. He never stopped being a thief, even when he was on camera,” says Mann, referring to Santucci’s brief career in film and TV. “Santucci was a sometime informant and a full-time professional thief.”

Portraying him was James Caan, who died last month at 82. “I loved him. He was outrageous,” Mann says, recalling the time Caan told a top film executive he should quit, “and then proceeded to list all the reasons why this particular executive ought to fire himself.”

From “Thief,” Mann moved on to classics like “Manhunter,” which introduced Hannibal Lecter to filmgoers, and “The Insider,” which earned him three Oscar nominations. “Thief,” “Heat” and 2004’s “Collateral” marked him out as a peerless chronicler of modern Los Angeles’ criminal underworld.

Michael Mann’s 1995 “Heat” has become the definitive L.A. crime film, but probably no one has done more lately to celebrate the epic tale of cops and robbers than a movie critic in Sydney, Australia.

The most indelible scene in “Heat” is a casual meeting between McCauley and Hanna. In their first scene together, De Niro and Pacino play deadly adversaries who share a grudging respect for each other’s drive and professionalism. The scene is based on a real-life encounter described to Mann by detective Charlie Adamson, former partner to Dennis Farina, who left the Chicago Police Department to pursue a successful career in Hollywood. Adamson, who was dropping off his cleaning, looked across the street and saw the real-life McCauley going into Belden Deli.

“There was about to be a shootout in the parking lot, and then Adamson said, ‘Come on, I’ll buy you a cup of coffee,’” Mann recalls. That single moment of enemies breaking bread “opened up a whole world to me — respecting and admiring the professionalism of McCauley” though Adamson would “blow him out of his socks at the drop of a hat. Both can be true. It’s not a contradiction.”

Adamson was part of a team that gunned down McCauley in 1964.

The sequel-as-novel is just the latest twist in the long cross-genre journey of a story that’s been Mann’s constant companion throughout his career. He began writing the script in the 1970s, eventually turning it into a 1989 TV movie, “L.A. Takedown,” before reworking it into the 1995 feature film. “I’ve met the real people that are in this book and have been in the milieus that are in this book,” he explains. “In the real world, this stuff is way more exciting than anything you can make up sitting in a room in L.A.”

That hard-earned authenticity, based on insider knowledge and a journalistic eye, is a prized commodity in crime fiction, from the thrillers of former cop Joseph Wambaugh to ex-reporter David Simon’s “The Wire.” Mann, who comes by his expertise via decades-long relationships with cops and criminals, has now brought it to both the screen and the page via the same narrative.

What the 27-year-gap has allowed Mann to do is mark the impact of time on both mortal men and the crimes they perpetrate. Toward the end of “Heat 2,” Shiherlis finds himself on the precipice of a new world in transnational crime — software systems that can penetrate any defense or shield offenders from crime solvers. He realizes bank jobs like the ones he pulled off with McCauley’s crew are going the way of the dinosaur.

Mann would like “Heat 2” to become a big-screen movie, and talks are in the works to make it the 79-year-old director’s next film after he wraps his current project, “Ferrari,” starring Adam Driver, Penelope Cruz and Shailene Woodley and shot in Italy (hence the Zoom from Rome). But time marches on in Hollywood too; the future of entertainment appears to be the small screen, which is what makes the novel, easily adaptable to film or streaming, the ideal form.

“I think what we’re doing evolves so rapidly it’s impossible to predict what’s going to be the best way to make a presentation 18 months from now,” says Mann, who most recently directed the pilot of “Tokyo Vice” for HBO Max. “I love streaming, we really are in a continuing golden age. The writing and content on television is fantastic.” He shrugs, glancing at his computer. “But of course I want this on the big screen.”

From Portugal, Spain and Scotland to Sedona, Ariz. The summer’s most anticipated thrillers will satisfy your wanderlust no matter your plans.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.