Review: The putrid waste of Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel, ‘Lapvona’

On the Shelf

Lapvona

By Ottessa Moshfegh

Penguin: 320 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

In Melissa Broder’s “The Pisces,” it’s “pink and slimy.” Ling Ma’s “Severance” has “an ugly sea cucumber.” In Ottessa Moshfegh’s “Lapvona,” the designated putrid penis is described as “greasy,” and though I know she didn’t start this daisy chain of repulsive anatomical description, I hold her most responsible for the sheer bounty of it. This is her territory.

“Greasy penis” is the ultimate Moshfegh-esque word pairing: sex-adjacent but unenticing. It doubly connotes glandular filth and manual labor, and it’s just banal enough to leave you annoyed with yourself for caring about how gross it is.

Moshfegh, in her fourth novel, thrives in the mire, a happy little worm sliding dirt down her gullet. When I read her work, I imagine Monty Python’s oppressed serf calling out, “there’s some lovely filth down here,” gleefully harvesting a great big pile of squelching sludge.

Unsurprising, then, that Moshfegh has ended up with a novel set in the Middle Ages. Lapvona is a medieval domain with Eastern European overtones — a Magda and a Grigor and a Dibra are wandering around. The backdrop: breeze-rustled forests and mountains, loamy smells and more sheep than a Scottish postcard (until Moshfegh gets her hands on the place and dries it out into a Sahara).

Celebrated for her novels, occasionally vilified for a persona she can’t control, the author of “Death in Her Hands” is our prophet of loneliness.

There is a gluttonous priest and a power structure so lopsided that this grotesque little fable somehow turns into a workplace satire, like quite a bit of Moshfegh’s earlier work. Except in this case the office is a fiefdom and instead of cubicle spats there are marauding bandits, a punishing drought and an unfortunate episode of cannibalism that ends with a “regurgitated pinky toe, small and roasted, its little nail sticking out.”

Having ratcheted her perversity up to an 11 in her fiction — in “Eileen,” the main character bare-hands her crotch in public and in “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” another character has her anus waxed in her sleep — Moshfegh cannot resist throwing everything she’s got at “Lapvona.” The main character soils himself 40 pages in. He sucks from his 100-year-old wet nurse’s papery nipples until “her pubis would pulsate and emanate a smell.” There is plenty more. Filth, famine, pillories, infection, crushed skulls, rape, hanging, self-flagellation, eyeballs detached, eyeballs replaced and a grape that makes its way from a rectum to another orifice. Also, murdered children all over the place. Yet somehow not an ounce of feeling.

Subtlety, in case you couldn’t tell, is not Moshfegh’s strong suit. Villiam, the lord of Lapvona, is named so closely to the word “villain” that auto-correct is fighting me on it as I type. And though “Lapvona’s” locus eventually moves up the hill to his stately manor, the story belongs more to Marek, a “deformed” 13-year-old boy with a “misshapen” head, “twisted” spine and “bowed” legs, the product of rape and a failed herbal abortion, cursed from the moment his lumpen ginger head spilled out of his wretched mother’s body onto his shepherd father’s dirt floor.

As for plot, there’s plenty. It’s sprinkled on top, however, like the crumb on a cake, added for some crunch but ultimately not baked in. Marek, who shares Moshfegh’s conviction that pain is good, that it brings him “closer to his father’s love and pity,” eventually sins too deeply for a mere beating as penance. He’s brought to Villiam’s manor house and left there, at which point Lapvona — both the town and the novel — spin off-kilter.

At its best moments, “Lapvona” follows the ancient wet nurse, Ina, from her days as a young maiden through the illness that blinded her and into the cave where she survived for decades on roots and grasses, cultivating her role as a mystic. What’s startling is how languidly Moshfegh can describe beauty when she wants to. The “silver bark” on apple trees “thick as armor and laced high with the scars from years and years of villagers etching their names with Xs.” The chamomile, cornflowers, ferns, irises and rustling grasses of the fields.

But the balance tips so far toward darkness that even if we read this as a fallen paradise — salvation is the hope and prayer of every character, even the dimwit Villiam — it’s hard to see what message this world has for us except that life is hell. “Lapvona” is an endurance test, as if Moshfegh wants to break the reader to see if the novel can stretch beyond its audience.

The poet, viral tweeter and author has a new novel, “Milk Fed,” imagining an explicit affair between a damaged Hollywood loner and a plus-size woman.

Characters in Moshfegh’s most successful work have always used the social contract to wipe their asses. The titular character in “Eileen” embraces filth (she keeps a dead mouse in her truck glove box and revels in her bowel movements) so she doesn’t need to care about not fitting in. The unnamed protagonist in “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” pushes back against the early-aughts upswing in self-branding and zealous workaholism by conking herself into a coma. That novel was also stealthily about Sept. 11 — both the costs of solipsism and the limits of disaffection. Its shock and awe carried some cultural weight. But with “Lapvona” I only feel dyspepsia.

I’m angry at the waste — not the ample human waste but the missed opportunities. Moshfegh is a brilliant chronicler of the absolute corruptibility of any small dose of power, and a medieval town on the brink of recognizing the violence inherent in the system (there are those Monty Python peasants again) is just the right place for her dispassionate wit.

Jacques-Louis David’s 1798 painting “Portrait of a Young Woman in White,” which was used for the cover of “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” has taken on a new cult status since the novel was published. (You can buy a cloth mask that features a cropped version with no face but a barely covered nipple front and center — a detail Moshfegh probably would enjoy.) I often visit the original on the second floor of Washington’s National Gallery, where the young lady appears alternately peeved, dismissive and bored, perhaps depending on my own mood.

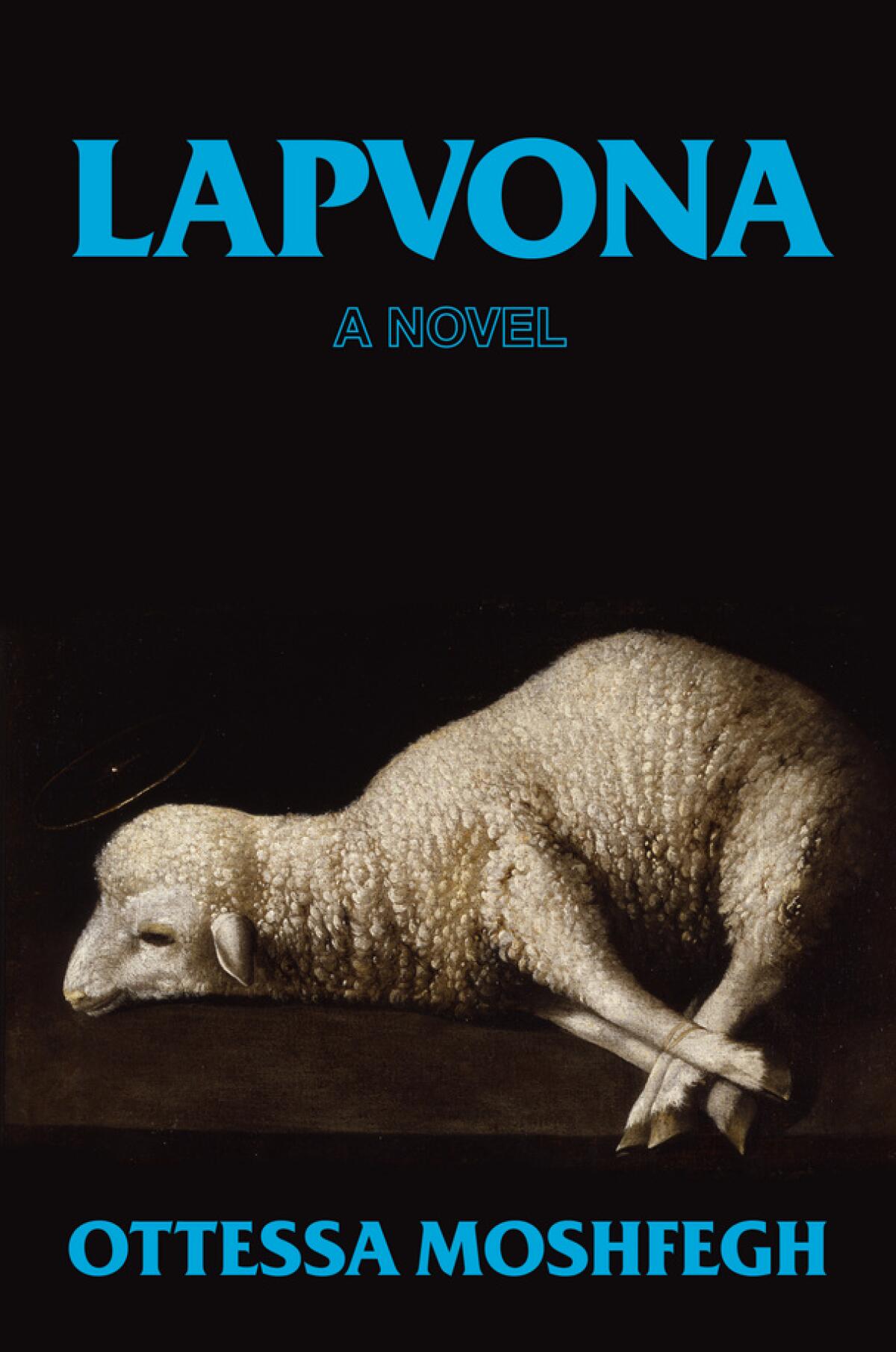

“Lapvona” tries a similar trick with Francisco de Zurbarán’s “Agnus Dei,” its subject matter a bound lamb presented for sacrifice. Where David’s painting captures the eternal exasperation of modern life inherent in “My Year,” the Zurbarán fools us into expecting a different novel altogether. Here’s this fleecy white creature, submissive and prepared for the bloodbath soon to come, a pure being, elevated far above the muck. Then again, maybe we are the lamb.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

Bethanne Patrick’s June highlights include Tom Perrotta’s ‘Election’ sequel, essential new war histories and a fresh look at females of all species.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.