On the Shelf

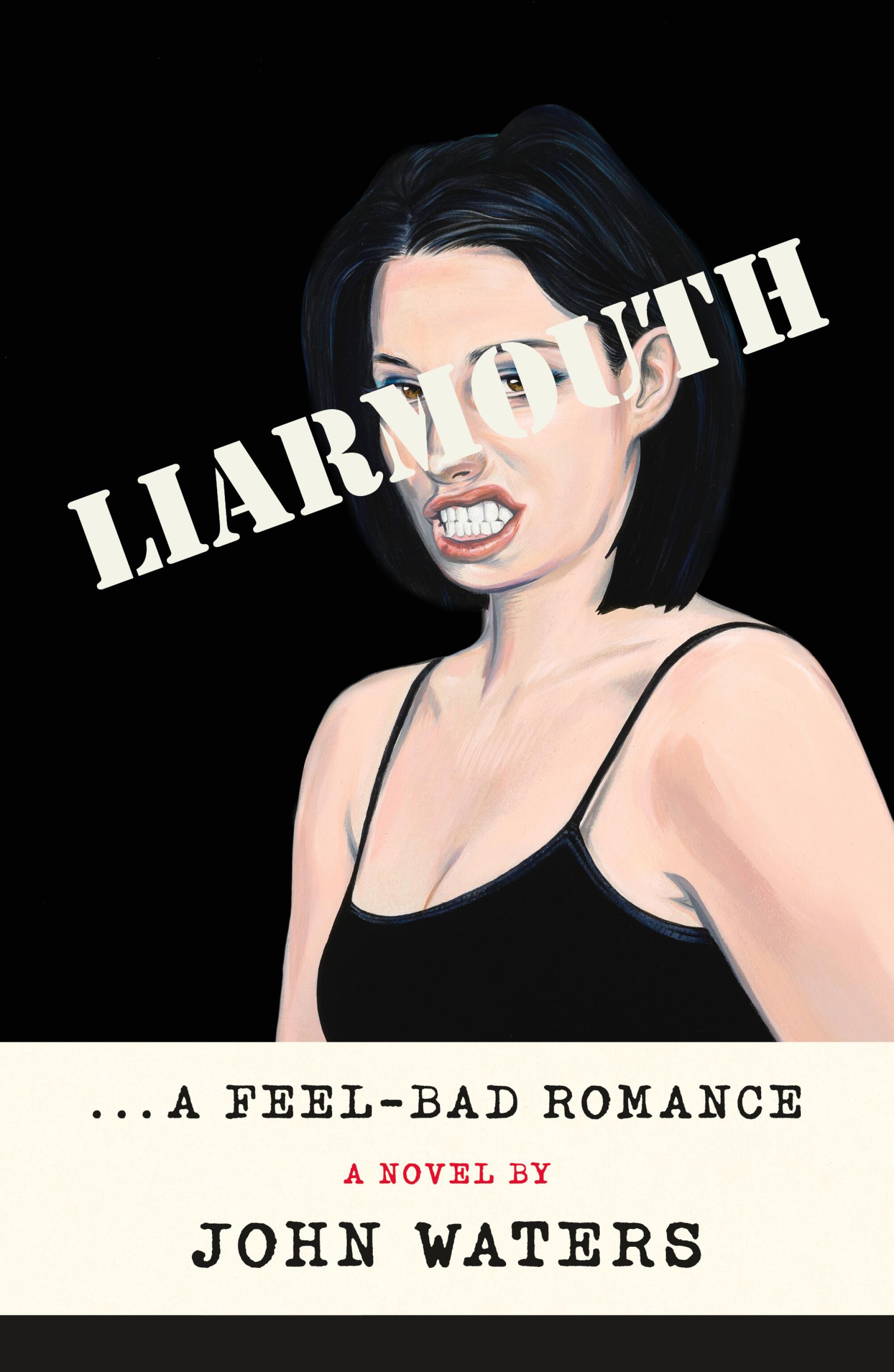

Liarmouth: A Feel-Bad Romance

By John Waters

FSG: 256 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When you get into a car with John Waters, the infamous filmmaker behind transgressive classics such as “Pink Flamingos,” “Hairspray” and “Serial Mom,” there’s a part of you that wonders if you’re being kidnapped, or at least conscripted into one of his anarchic characters’ outrageous crimes. If you too might be found guilty of “first-degree stupidity” in Divine’s kangaroo court or forced to star in a film by a “cinematic terrorist” like Cecil B. Demented.

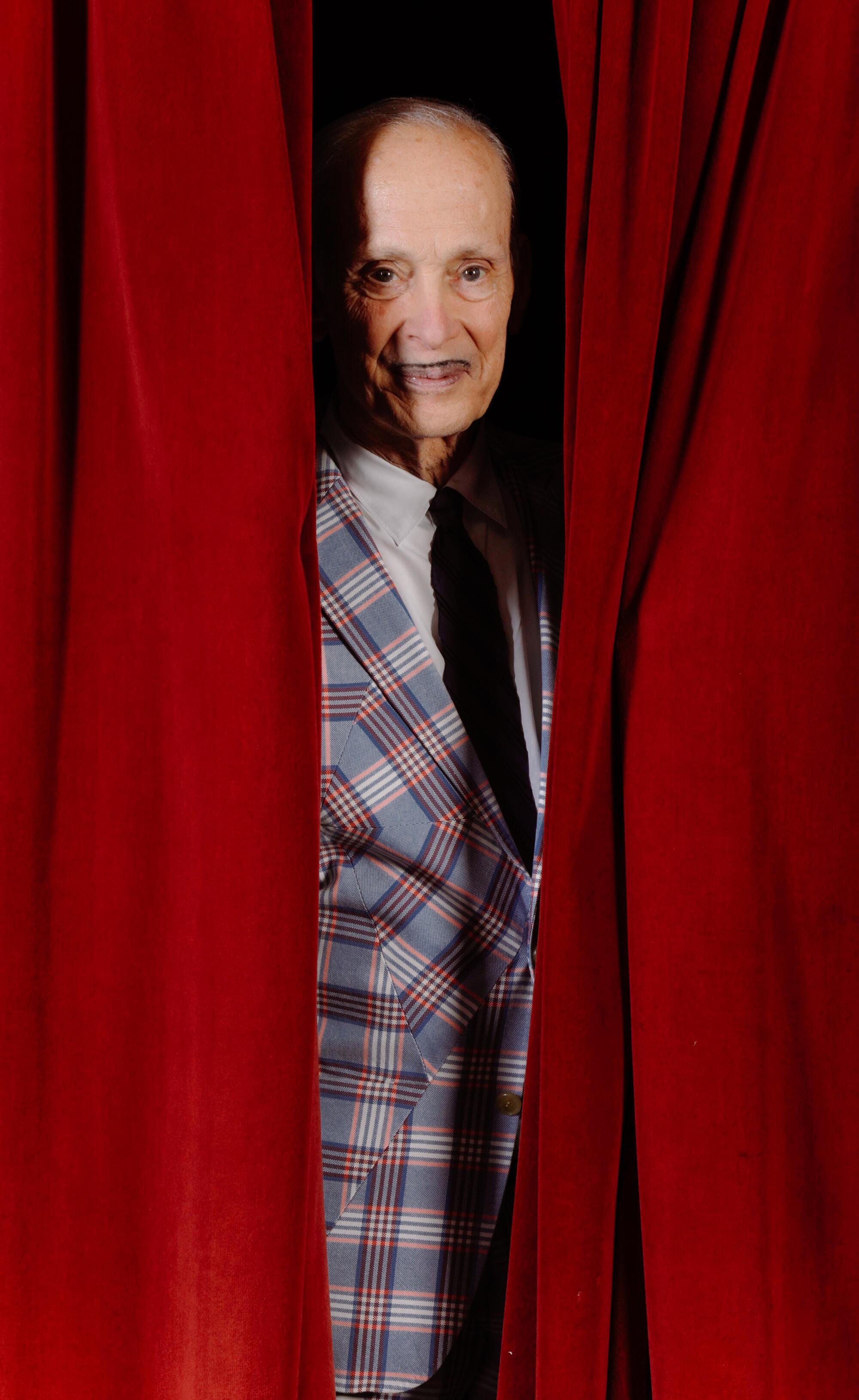

The reality is more mundane but entertaining nonetheless. On a crosstown drive from the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel to the Aratani Theatre in Little Tokyo, Waters’ stylish plaid suit of Easter pastels is the loudest thing in the vehicle, aside from my laughter at his witticisms. He’s a subversive and playful conversationalist, but — not to ruin his reputation — also sweet, gentle, almost subdued. Even when gleefully grabbing third rails like “cancel culture” and other topics prone to infuriate one end or the other of the political spectrum, he manages to sound gracious, measured and strangely wholesome.

Waters is on his way to speak onstage with Ginger Minj, a finalist on “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” on the last leg of his promotional tour for “Liarmouth: A Feel Bad Romance.” Though it is his debut novel, Waters, 76, has written almost as many books as he has films — including the national bestsellers “Role Models,” “Carsick” and “Mr. Know-It-All.” He says he’s always considered himself a writer first — and an avid reader too. Having collected books since he was 14, he has more than 11,000 dispersed across his homes in Baltimore, New York and San Francisco.

Our regularly updating 2022 Pride guide to culture will feature novels and memoirs from LGBTQ icons, must-see TV series, music, movies and much more.

Waters’ novel isn’t exactly a departure. It’s full of wild characters and shocking twists — pet face-lifts, trampoline cults, a talking phallus — but the first idea that came to him was a woman who stole luggage at airports. “High concept,” he tells me. “I’m used to the movie business, so I always need a title and a one-sentence description.”

The exploits of Marsha Sprinkle — suitcase thief, con artist, inveterate liar — could have been a film. She and the other dramatis personae of “Liarmouth” feel like they’ve just walked off a Waters set still in character; the narrative braids perspectives together across different locations in a way that resembles cinematic crosscutting.

“It was a movie idea in the beginning,” he admits, but it quickly became something else. Not only did the novel allow him to avoid some of the more difficult aspects of filmmaking — “I didn’t have to worry about budgets or the MPAA” — but it let him dive deeper into the debauched minds of his characters.

John Waters’ new collection of essays, “Mr.

Of course, novels too have their constraints, especially in the age of sensitivity readers. “We sent it to one, but she never called us back,” Waters quips. “So we don’t know what happened to her. Did she drop dead? Did she quit publishing?” But seriously: Waters says he vetted the manuscript with three generations of women, and he did make changes. Not that he thinks it’s the artist’s job to worry about causing offense.

“I worry they wouldn’t laugh, but I don’t worry about their sensibilities,” he says, “because if they’re buying a book by me, then they’re already wanting to be taken into a world that maybe makes people a little uncomfortable.”

Yet even in Waters’ filthy world, there may be something approaching an ethic. At the end of the novel, Waters thanks his editor, Jonathan Galassi — a giant in publishing who has translated Italian poets and edited everyone from Joseph Brodsky to Jonathan Franzen — for understanding “my perverse morality.”

When I press Waters on what his “perverse morality” might entail, he explains: “There are rules in my world. The right people win: the ones who believe in themselves, who exaggerate what others might think is wrong, embrace it and don’t really care what other people say, but aren’t judgmental or jealous. The other people are imitative, bitter, judge other people, try to act rich when the rich should hide it.”

One of the biggest sins in Waters’ world is taking yourself too seriously. With the advocates of “political correctness” he expresses mostly solidarity, “but then the self-righteousness is the one thing that I don’t agree with. We used humor to fight when I was young.”

Later, backstage at the theater, he adds, “We rioted for freedom of speech!” He still stands by it as an absolute principle even when it puts him in the crosshairs of his compatriots on the left. He seems legitimately worried about Americans becoming more and more siloed — increasingly speaking only to people with whom they already agree. This is why he reads conservative papers, why he recently went on Greg Gutfeld’s Fox News show, why he befriended — of all people — Andrew Breitbart, the late right-wing provocateur.

“I thought it would be a perfect show to have at Oscar time,” the gleefully perverse filmmaker says of his gallery exhibition, ‘Hollywood’s Greatest Hits.’

Breitbart, after a taping of “Real Time With Bill Maher,” told Waters, “I’m the same as you; we learned everything from Abbie Hoffman. We’re just on different sides. It’s all showbiz.” Waters enjoys entering what he calls “enemy territory” because he thinks it’s important to “make each other laugh, which is the way to make each other listen.”

On the table in front of us are more than 500 “Liarmouth” hardbacks, which he signs without complaint, joking, “My handwriting looks like a good Cy Twombly painting.” To pass the time, I ask his opinion of the defamation trial involving Johnny Depp and Amber Heard. He compares it to a Douglas Sirk film. All he’ll say directly is: “I only know Johnny from when he was with Winona Ryder, Kate Moss and Vanessa Paradis, and they all broke up, and they all say fine things about him now. I never ever saw him be horrible to a woman.”

OK then, what about working with Woody Allen? “It was great. And I haven’t given the money back. I spent it.” Would he work with the filmmaker again? “I don’t know, but I paid to see his last two movies.” Waters doesn’t believe in “canceling” people because “most artists would be canceled.” He adds: “I’ve forgiven people that have committed murder, so I’m not judging other people.” Waters means it: He is friends with former Manson “family” member Leslie Van Houten, and he laments what he considers the “unlawful” re-imprisonment of “Cry-Baby” leading lady Amy Locane over a drunk-driving death.

Waters even agrees with Elon Musk regarding Trump’s banishment from social media — though he is unambiguous about his “hate” for the ex-president who “ruined bad taste,” among other sins. (He’ll get the biggest laugh onstage tonight with the line, “There’s no such thing as karma: Divine’s dead, Trump’s alive.”) He is fine so far with the Biden administration, though Obama is his favorite. “Even though Michelle Obama beat me at the Grammys for best spoken word album. All that lobbying she did!”

The shock of the evening, though — a twist as strange as anything Marsha Sprinkle ever got mixed up in — is that the only White House he ever saw the inside of was Ronald Reagan’s, and the staff member who invited him was Lee Atwater.

In video testimony, Raquel ‘Rocky’ Pennington, Amber Heard’s best friend during her marriage, backs up allegations of violence by Johnny Depp.

“He was a huge fan of exploitation films,” Waters explains of the Republican strategist who spearheaded the racist ad campaign against George H.W. Bush opponent Michael Dukakis. “I took my boyfriend, who was terrified and never said one word the entire time we were there. I didn’t know all the horrible stuff Atwater had done at the time. I was just amazed that a Republican invited me. Later, I found out about Willie Horton and all that.”

At one point, Waters leans in close as if to share a secret: He is “down-low patriotic.” He confesses: “I think America’s the greatest country; I just don’t say that. But how else could I have this career? I couldn’t have it in a lot of places.”

It makes a lot of sense, when you think about it. In a weird way, Waters has become a piece of Americana — so inextricable from the national culture that his work can cross party lines as smoothly as Dolly Parton’s. “Pink Flamingos” is getting a Criterion rerelease for its 50th anniversary. Last year, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. Waters has somehow become not just mainstream, but respectable.

He’s about to go on stage, so I ask one final question: “When you were in your mid-20s making underground movies that shocked and offended so many, did you ever imagine you’d be so accepted by the culture 50 years later?”

“No,” he says. “But I never imagined not, either. I always thought things were possible.”

He talks with The Times about his novel “Truly Like Lightning,” Mormonism, the patriarchy, sex, political correctness and, of course, Harold Bloom.

Malone is a writer based in Southern California.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.