Review: The world that made and unmade the Notorious B.I.G.

On the Shelf

'It Was All a Dream: Biggie and the World That Made Him'

By Justin Tinsley

Abrams: 352 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

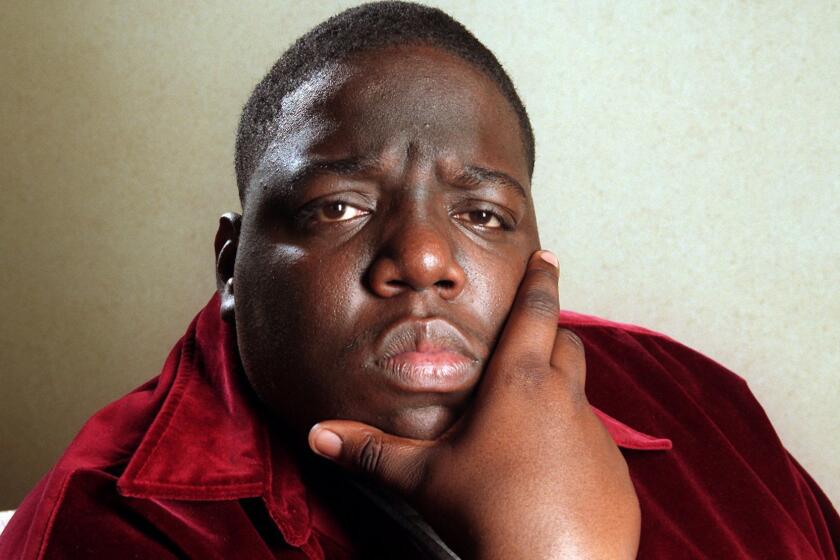

If you rob me, I’ll kill you. There are countless ways to express this idea, but probably none more clever than this: “There’s gonna be a lot of slow singing and flower bringing if my burglar alarm starts ringing.” That’s the Notorious B.I.G., born Christopher Wallace, on his aptly titled 1994 song “Warning.” Biggie plays two characters on the track, one calling the other to warn him of a plot against his life and his riches. Hip-hop doesn’t get much more creative.

At its best, Justin Tinsley’s new biography, “It Was All a Dream: Biggie and the World That Made Him,” pays tribute to that creativity — and to the short life and blinding talent of the rapper who loved it when you called him Big Poppa. (Biggie was shot dead in Los Angeles in 1997 at age 24.) The book excels at big-picture analysis, taking the mission in its subtitle seriously. In lesser moments, it piles up malformed sentences and typos at an alarming clip, but if you can get past those, it serves as a solid and incisive if rarely revelatory summary of a hip-hop legend’s life and art.

Tinsley starts with the early life of Biggie’s mother, Voletta Wallace — in her native Jamaica and her passage to New York. She saw America as a land of opportunity, much as her son would one day rap about the marvel of upward mobility in his hit single “Juicy.” Voletta settled in Brooklyn, where young Christopher would sit on their apartment stoop and watch the world go by: the hustlers, the working people, the schoolkids whom he would sometimes join in class, where he showed aptitude if not interest.

Biggie’s real school was the street; his goal was to make enough cash to ease his and his mother’s financial burden. He figured out early what the local crack dealers were up to. He liked their nice clothes and fancy cars. This would be Biggie’s first career, and it would one day inform the crime stories that gave his best work its lived-in authenticity. As Tinsley writes, “For a teenager making thousands of dollars just off hand-to-hand transactions, school was never going to be able to compete.”

Tinsley is wise to the two-way street connecting drug dealing and hip-hop — each a means of moving up in the world, one much more dangerous than the other. As Biggie himself rapped on the haunting “Things Done Changed,” “If I wasn’t in the rap game, I’d probably have a key, knee-deep in the crack game.”

Emmett Malloy’s documentary movie ‘Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell’ aims to show a different side of the late Notorious B.I.G.

But Biggie was no dummy. He knew there was no such thing as a career selling crack. He also had friends who could hear his raw talent — his wordplay, his wicked sense of humor, his gift for vivid, cinematic storytelling. Those friends eventually led him to a young, headstrong music executive named Sean “Puffy“ Combs, whose vision for Biggie went beyond street tales and tapped into his unlikely but considerable sex appeal. Combs is a big reason we have songs like “Juicy” and “Big Poppa,” pop-savvy cuts that allow the listener to luxuriate in Biggie’s charm.

“In the history of rap,” Tinsley writes, “it’s hard to think of many songs – if any exist – that serve as a more powerful introduction to an artist than ‘Juicy.’ In less than five minutes, Big managed to paint his life story in a way that, a quarter century later, the BBC would dub rap’s ‘quintessential Cinderella tale.’”

Unfortunately, rap didn’t prove to be a long-term career either. Tinsley doesn’t break any new news on the double-barreled tragedy of Biggie and Tupac Shakur. Their unsolved drive-by murders — Shakur’s in 1996, Biggie’s just six months later — will always be connected in the public mind, as they have been through multiple investigations and theories involving police corruption, retribution and the storied beef between West and East Coast rappers.

The author isn’t an investigative reporter, nor does he claim to be, and the subject has been examined about as intensively as any celebrity murder mystery of the past 30 years. Tinsley does provide context into the pair’s burgeoning friendship, which effectively ended with the 1994 shooting of Shakur at New York’s Quad Studios, for which the West Coast rapper blamed Biggie.

Notorious B.I.G. was leaving a music industry party at the Petersen Automotive Museum, sitting in the front passenger seat of a Chevrolet Suburban, when his killer pulled up alongside in a dark Chevy Impala.

One of the new biography’s problems is that this has all been covered elsewhere, including in other biographies (Cheo Hodari Coker’s “Unbelievable”) and documentaries (“Biggie: I Got a Story to Tell”). Then there’s the error-prone syntax — infelicities in editing and writing that add up quickly. “Such was the layout of was Christopher Wallace’s trap house,” reads one typo among many. Tinsley has George H.W. Bush winning a “whooping” 426 electoral votes in the 1988 presidential election, suggesting a cough rather than a blowout. Sometimes the same phrases are repeated in the space of a single page. In small doses, such errors don’t matter much. Here they appear over and over again, taking the reader’s head out of the story. These are the kinds of things editors should catch. For some reason, they didn’t.

The book is stronger on the macro level, filling in the context of Biggie’s life with sharp sketches of the people, events and social currents that accompanied Biggie’s rise. Tinsley is particularly insightful on Combs, who at the time was struggling for redemption after a charity event he promoted at the City College of New York led to a stampede and the deaths of nine people — and also on Shakur, depicted as a socially conscious dynamo whose acute sensitivity came with violent outbursts and paranoia.

Tinsley also knows his ‘80s and ‘90s hip-hop. The easy story pits the East Coast against the West, but the fandom never split that neatly. Many New Yorkers were blown away by Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” (1992) and Snoop Dogg’s “Doggystyle” (1993), seminal L.A. albums that inspired Biggie, among others, to raise his game. Tinsley explains this less obvious dynamic with knowledge and perspective.

“It Was All a Dream” makes a fine starting point for those looking to discover what all the fuss was about and why Biggie still matters. No other artist since has quite combined the tools that made him unique — the mixture of hardness and vulnerability, the humor and the hardcore, all topped off by pure skill. There’s no telling where he would have gone, but this book does a fine job of tracing how far he managed to go.

Vognar is a freelance writer based in Houston.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.