How a book about abortion in 1960s France became the timeliest movie of the year

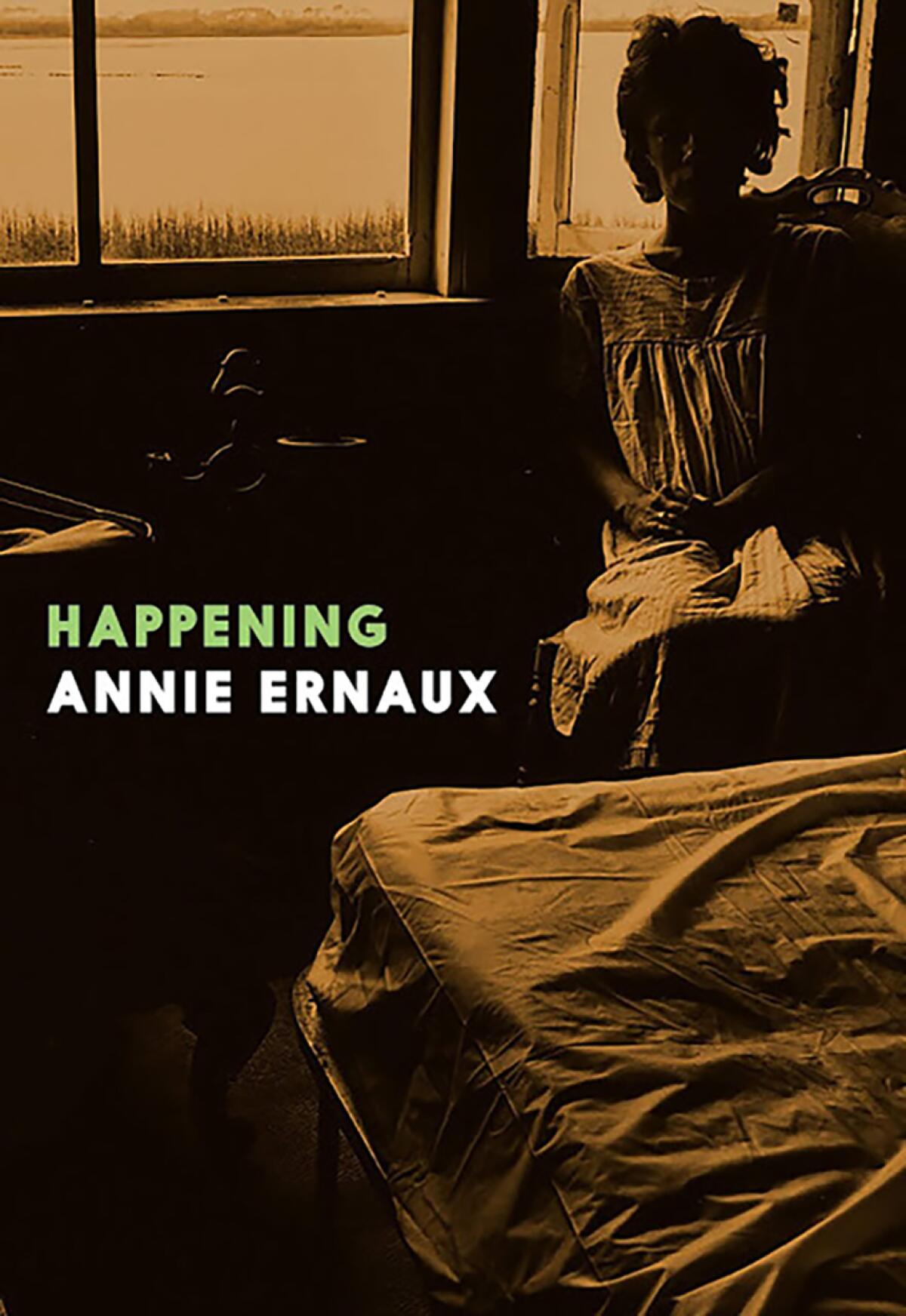

France in the 1960s is famous for its symbols of liberation: Bardot, Foucault, student rebellion (“under the pavement, the beach”). Yet nearly half the country lived with the ongoing threat of unwanted pregnancy, a looming dystopian nightmare. Contraceptives were illegal, as was abortion. In late 1963, Annie Ernaux, the first in her family to attend college, was months away from graduating when she learned she was pregnant. “Happening,” published in France in 2000 and in English a year later, is a memoir of her race to abort without dying or landing in prison.

Audrey Diwan’s movie adaptation, which won the top prize at the 2021 Venice Film Festival and opens in U.S. theaters this week, relates young Anne’s experience while omitting many of the author’s recollections and ruminations. But Diwan’s skillful interpretation couldn’t be more effective at transmitting Ernaux’s freshly urgent message in light of the ongoing rollback of women’s rights: Prohibiting abortion puts women in mortal danger.

Since the 1970s, Ernaux has published roughly two dozen compact, arresting memoirs of her life as a girl and a woman. Her 2008 capstone, “The Years,” furthered her project of “autosociobiography,” channeling a collective historical consciousness from which she views her own inner life as inseparable. With a signature blend of raw precision and spare lyricism, she’s turned a methodical lens on her adolescence, family relationships, illnesses and love affairs.

In her memoirs, Ernaux plunges us headfirst into her experiences, particularizing her recollections with cultural, commercial and personal artifacts — news stories, groceries, snapshots — and distilling insights from her present perspective. As Diwan jettisons the latter two components of “Happening,” the narrative loses some of what makes Ernaux’s work sui generis, but in so doing it takes on new universality. The result reminds viewers that this one specific happening, in all its peril and terror, stands in for millions of others.

A draft opinion circulated among Supreme Court justices suggests that earlier this year a majority of them had thrown support behind overturning the 1973 case Roe v. Wade that legalized abortion nationwide, according to a report in Politico.

At age 23, Anne is at the top of her class at her Normandy university. Her parents run a small-town café (the incomparable Sandrine Bonnaire plays Anne’s mother on-screen). But Anne is determined to teach and write. Finding herself pregnant, she embarks on an odyssey to obtain an abortion. Doctors and classmates are loath to discuss it for fear of prosecution. Anne’s lover makes clear that it’s her problem to deal with. Even in medical textbooks, information is scarce.

Increasingly panicked, Anne is unable to concentrate on school. She makes an unsuccessful attempt with knitting needles at home. Finally, an acquaintance refers her to a Paris abortionist off a literal back alley, where she has the procedure at 12 weeks. It’s costly and excruciating, with no medication or follow-up care. It takes three days for Anne to miscarry in the bathroom back at her dorm; then, she begins to hemorrhage. The on-call campus doctor sends her to the ER, where she’s lucky the event is not ruled to be an abortion — and lucky to get out alive.

The abortion allowed the author — once she recovered — to finish school, start her career and have children when she was ready. Ernaux’s first published book, the autobiographical novel “Cleaned Out” (1974), dealt with the incident as the ultimate step in her coming of age. She turned to memoir shortly thereafter, but she always felt compelled to recount her three-month ordeal in full; after 35 years, she set out to excavate it. Using her diary and still-vivid memories, she reconstructs the crisis, mentally and physically retracing her steps. At times, she’s unsure she’ll be able to persist. Rather than include the adult narrator in the film, Diwan transfers Ernaux’s anguish directly to viewers through a visceral identification with Anne.

Diwan, originally a novelist, co-wrote the policiers “The Connection” (2014) and “The Stronghold” (2020) and made her directorial debut with the domestic drama “Losing It” (2019). Ernaux advised her on “Happening,” giving notes on several drafts of the script. The film’s star, Anamaria Vartolomei, executes the role with laser-beam intensity. As Anne, she embodies alarm, agony and determination all at once in a performance Ernaux called “overwhelmingly true and spot-on.”

The camera work, intimate and unrelenting, moves us through her predicament with her. With Anne’s rising despair, her surroundings grow blurry, the ambient sound increasingly unintelligible. In the film’s press materials, Vartolomei reveals that for the climactic labor scene, Diwan put a metronomic device in the actor’s ear, then steadily turned up its volume. When Anne returns to class at the movie’s end, we share her overwhelming sense of deliverance.

Many have failed to adapt Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel ‘The Power of the Dog.’ Jane Campion was perfect for it; both author and director deserve adulation.

What makes Ernaux’s voice essential on the page — the textural immersion in her memories and the way she plumbs them for epiphanies — also makes it hard to bring her work to the screen. Diwan forgoes these aspects of the book but serves the author’s intent by re-creating the emergency itself. It was important to the filmmaker that “Happening” not feel distractingly like a period movie; hence the paucity of contextual details.

By contrast, Ernaux recalls material specifics as integral to her experience: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, a ubiquitous song by a closeted nun, a screening of “Battleship Potemkin” where she underwent contractions. These points of contact with the outside world formed tenuous toeholds for the young Ernaux, and they personalize her narrative in a way the film deliberately avoids.

Diwan also elides a piece of the story between the protagonist’s hospital stay and her exams, a tender telling of how Anne savored her reprieve with something like spiritual ecstasy. But including these moments would make it a different movie, perhaps one with slightly more time to spare. Although Diwan takes care not to shock for effect (in fact, omitting a few of the text’s darkest passages), she prioritizes immediacy— a choice Ernaux affirmed. The effect is a version of the story that calls in contemporary viewers, reminding us what the stakes are today, when women in a growing number of U.S. states are faced with enduring what Ernaux did almost 60 years ago.

An experience as common as abortion ought to be too mundane, so many years later, for dramatic storytelling. Regrettably, the abortion quest remains the engine of a reliably high-stakes narrative arc. Where a hero might journey into the future, a heroine journeys just to have one.

As a genre, abortion-quest films are almost always two-handers, enlisting a female friend or family member, whether the result is a grim tale of compromise (“Never Rarely Sometimes Always,” “4 Months, 3 Weeks, 2 Days,” last year’s “Lingui”); an unlikely occasion for comedy (“Grandma,” “Plan B,” “Unpregnant”); or something in between (“One Sings, the Other Doesn’t”). But amid all of the coat hangers, mustard baths and pennyroyal potions on-screen, “Happening” is most striking for Anne’s isolation. As in Ernaux’s life, the protagonist is on her own, a reality more common than movies let on.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

In “The Years,” Ernaux alludes to later involvement with a Jane Collective-like clandestine network facilitating safe abortions. She writes of her participation in the movement to decriminalize the procedure: “It was up to us to stop, for the very first time, thousands of years of blood-soaked deaths of women.” Six decades later, the U.S. Supreme Court is poised to return us to those dark days. For many, “Happening” is brutally relevant — and may be well into the future.

Johnson’s work has appeared in the Guardian, the New York Times, the Los Angeles Review of Books, the Believer and elsewhere. She lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.