On the Shelf

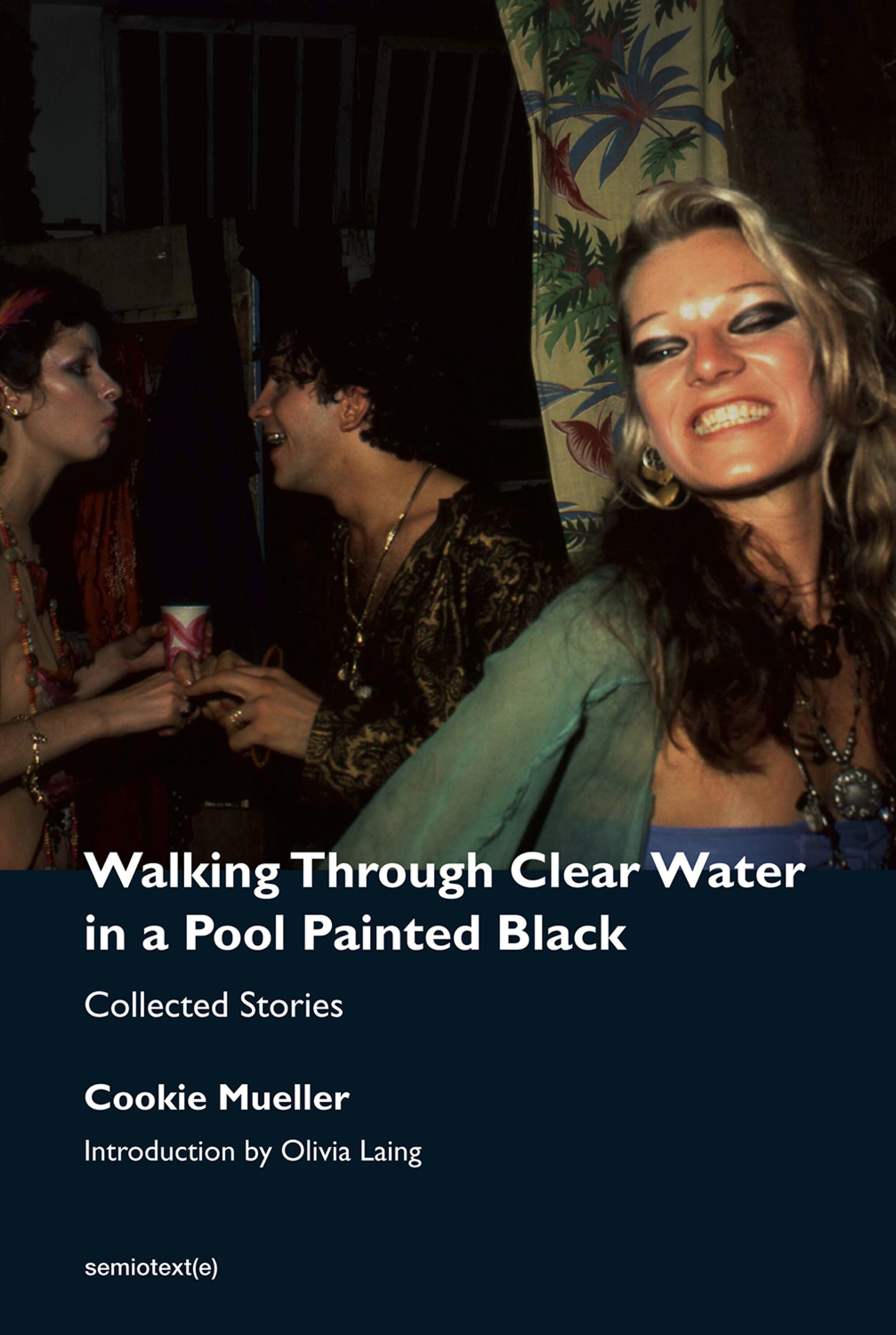

Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black, New Edition: Collected Stories

By Cookie Mueller

Semiotext(e): 432 pages, $18

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The first time I saw a photograph of Cookie Mueller, it was the portrait Nan Goldin had taken of her in her casket. Shimmering in gold, like a mosquito encased in amber, Mueller lay supine, arms crossed in front of her like an Egyptian pharaoh.

Mueller was an It Girl, discovered by John Waters for his film “Multiple Maniacs” in 1970. When Mueller met Waters, she writes, “I felt like I was meeting my new family.” After learning the cult filmmaker was born prematurely, “I envisioned him as an infant, compact like a pound cake, lying in a clear plastic preemie life support box ... already rococo and bursting his bunting wrapper with his dreams and plans of film scenarios.”

“Walking Through Clear Water in a Pool Painted Black,” a newly expanded collection of her complete stories (some true, some not, some in between), provides many opportunities to fall in love with Mueller. Burning her friends’ house down; being nearly sacrificed by Anton LaVey on Mt. Tamalpais; saving her friend from overdosing at his birthday party; describing the birth of her son, Max: “I was the grand martyr. Prometheus knew no pain like this. Lamaze had lied”; fleeing her would-be rapist in the dead of night; escaping a serial murderer in a G-string. “Why does everybody think I’m so wild?” she asks. “I’m not wild. I happen to stumble onto wildness. It gets in my path.”

“I thought it would be a perfect show to have at Oscar time,” the gleefully perverse filmmaker says of his gallery exhibition, ‘Hollywood’s Greatest Hits.’

Semiotext(e) first published Mueller in a collection of stories from her life under the same title in 1993. Those are expanded and grouped by location: Baltimore, Provincetown and New York. Also included are Mueller’s columns, “Ask Dr. Mueller” and “Art and About.”

New is a series of disarming fables. In “Valerie Losing 2,” a woman wakes up to discover one of her toes is missing, and also: “In the last fifteen years she had lost a lot, beginning with her virginity. She had lost two husbands, countless girlfriends, passports. ... She had lost so much it was just something else to mourn over for a bit. She took it in stride.”

The title of the collection comes from the story “Route 95 South — Baltimore to Orlando,” in which Mueller and her friend Lee get picked up by a man named Cleo who is robbing empty houses along the expressway. When Mueller spies a small gold statue of Pan, she puts it in her bag. Though he has his back to her in the car, he tells her to take it. She apologizes, shocked that he caught her. “You can’t hoodwink a hoodwinker.”

After getting dropped off in Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp, she writes: “There was no moon. The sky was like black cotton batting that enveloped us in a way that felt like walking through clear water in a pool painted black. ... We kept walking and walking, blindly in the dark, along the deserted road that we couldn’t see underfoot. There were no points of horizon, no beginning, no end to the highway.”

Many have stumbled onto wildness and never written anything of consequence. But Mueller was always writing, putting one foot in front of the other toward a horizon with no beginning and no end.

Catherine McCormack, a course director at Sotheby’s, talks about her new book, “Women in the Picture: What Culture Does With Female Bodies.”

The evidence of her talent and wit bubbles off the page. Mueller writes with all the charm and warmth of Eve Babitz. When her mother gets a hold of the script for “Pink Flamingos” and reads that Mueller’s character has sex with a chicken, the result is explosive. “ART?!?!?! ART!?!?! THIS ISN’T ART!!” ... “Mom, hold on. Sit down.” Waters pulls up in the driveway. “IS THAT MANIAC OUT THERE?!? I’M GOING TO GIVE HIM A PIECE OF MY MIND.” “Did she read the script or something?” Waters asks. “She was brought up in the Deep South as a Southern Baptist. That was high drama,” Mueller says. “She’s an actress.” Waters responds with a laugh: “Maybe I ought to give her a part in the film.”

After several trips to Italy, Mueller fell in love with an artist named Vittorio Scarpati. The two were married in New York in 1986. At the time, she was writing “Ask Dr. Mueller” for the East Village Eye, offering health advice without any professional qualifications. The column begins with queries about cellulite and apple cider vinegar. Then, in a response to one correspondent who complains of a small penis, Mueller abruptly writes, “I’m not going to talk about AIDS ... I’ve had too many beloved friends die lately from diseases contracted when the immune system breaks down. I’m tired of going to wakes. I miss these people.”

When Scarpati’s lungs collapsed, many blamed the particles (and the many cigarettes) he had inhaled as a sculptor and restorative artist. But it was AIDS. In one of her last columns for Details magazine, Mueller wrote that Scarpati had been finally driven to create his own art when he was in the hospital. “Did he need to be physically tied down to finally do his important work?” she asks. “Vittorio has learned that like a flood of sunlight, hope can vanquish gloom ... I hope he comes home soon.”

Mueller was living on borrowed time too. While Scarpati was in the hospital, she and her friend, artist Scott Covert, went to Provincetown, Mass. “She had this card that I found,” Covert remembers in Chloe Griffin’s oral biography of Mueller, “Edgewise.” “It had something she would repeat to herself, for some kind of visualization, like a mantra: ‘I will live long enough to write my novel — one year, two years ... .’ I don’t know what the novel was about; maybe her life. She wanted to dedicate it to her son.”

Goldin photographed Mueller standing in front of Vittorio’s casket. “I’d always believed that if I photographed anything or anyone enough, I would never lose them,” Goldin wrote in her 1998 book “Couples and Loneliness.” “With the death of seven or eight of my closest friends and dozens and dozens of my acquaintances, I realize there is so much the photograph doesn’t preserve. ... It doesn’t preserve a life.”

Mueller never got to finish her novel. She died of AIDS on Nov. 10, 1989, at 40, just three months after Scarpati. “Walking Through Clear Water” is an important recovery of the work she did manage to get down. “I started writing when I was six and have never stopped completely,” Mueller writes. “I wrote a novel when I was twelve and put it in cardboard and Saran Wrap, took it to the library and put it on the shelves in the correct alphabetical order.”

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

The water might be clear but the pool is painted black. The newly collected writings — including the gut-wrenching “Last Letter,” which closes out the collection with the directive “Courage, Bread, and Roses” — bolster the evidence Mueller is much more than an It Girl. She is a writer. Though most of the people who knew her (or knew of her) focus on her vibrant, untameable energy, when that energy dissipates it leaves a yawning black hole. Mueller’s writing, and struggle to write, can’t be separated from her experience of living.

In that sense, paradoxically, Mueller lives. To quote the writer Kathy Acker, who died from breast cancer at the age of 50, “I’m not superstar s— and will never be. If anything, I’m what happens after death, which is writing.”

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.