Review: Chelsea Bieker’s Central Valley stories teem with awful people. You’ll love them anyway

On the Shelf

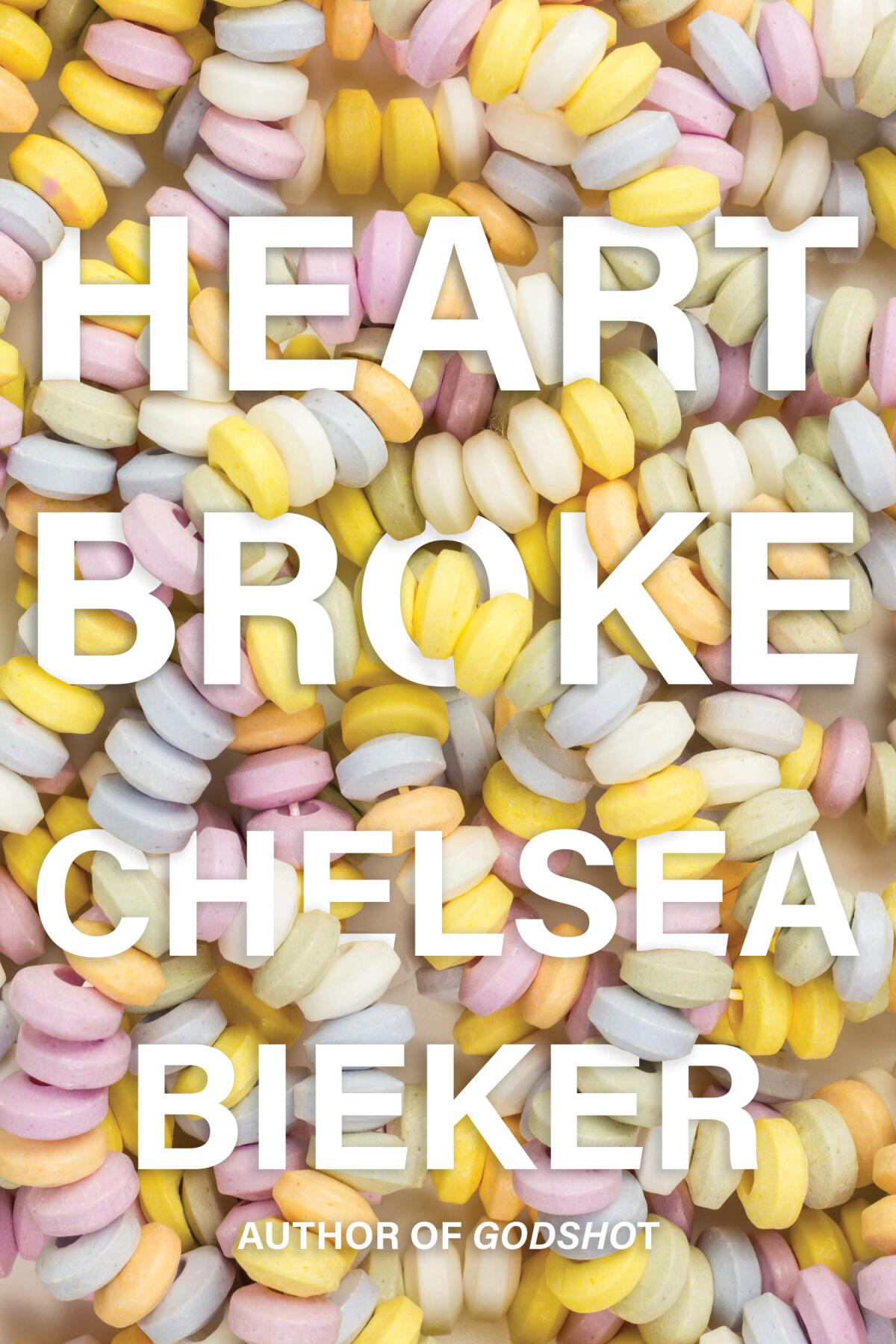

Heartbroke: Stories

By Chelsea Bieker

Catapult: 288 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The title of Chelsea Bieker’s first collection of short stories couldn’t be more apt. “Heartbroke” is full of cornered women, poisoned relationships, lonesome California landscapes and quiet violence.

The title story consists of letters from a mother to a son, repeated attempts to explain how the death of two children before his birth has made her the way she is. In the story “Women and Children,” an addict steals another addict’s baby and goes on the lam. “Fact of Body” follows a sex worker and her adolescent son living out of their car in a polluted beach town. Elsewhere, a girl locks her mother in a shed to keep her from running off with a mad pastor and a son does the unthinkable to protect his mother.

Bieker has some clear themes, to be sure: The ways mothers and fathers and children harm one another; how addiction weaves its way into everyday life, shredding the fabric that once held it together. Bonnie and Clyde-type couples delude themselves and each other; people are exposed to the world’s depravity much too soon, their half-formed soft parts calcifying. The urge to destroy, emotionally or physically, is quite often fulfilled — and without much remorse.

Please excuse me while I tell you about something someone said in my fiction MFA workshop: One student observed of another’s characters that they felt cared for, that they were rendered with palpable tenderness. As someone with disdainful tendencies in her writing, I’ve never forgotten this comment, which implies it is possible to look after people in fiction without lapsing into sentimentality. That characters can steal babies and catfish their best friends and still make your eyes well up, as they do in the short stories of Denis Johnson, Mary Gaitskill and darker shades of Ray Bradbury.

Chelsea Bieker’s ‘Godshot,’ a surreal debut novel set in the parched Central Valley, depicts a fundamentalist rain cult and sex worker resisters.

“Heartbroke” falls within this tradition of writers fixing their lenses on the underbelly of small-town and rural America, examining the dark things that happen there before they entrap you into empathizing with people you might never meet in life — or want to. Bieker’s characters do bad things, sometimes terrible things. You want to yell at them, “Don’t give that guy oral sex in a public restroom with a baby watching!” or “Don’t take up with that man who is clearly a sociopath and is going to beat you while spreading peanut butter across his belly and waving a gun!” But inevitably they do, and when they do, it is with tenderness and a weird kind of grace. It’s terrible to watch but also fascinating, because their terrible choices carry a whiff of the mundane, the ordinary, and when they survive — if they survive — you can’t help admiring them for it.

Bieker’s 2020 debut novel, “Godshot,” is a sister-wife to this collection. The story of a pregnant teenage girl whose mother runs off with a sex-trafficking cowboy, leaving her in the care of her bizarre widowed grandmother and a soda-drinking, rain-conjuring cult, it’s set in the same forlorn towns and sunburnt fields of Central California and peopled with similar kinds of characters — phone sex workers; raisin farmers; women abandoning women; women saving women; toxic, deluded men. Not only do these two books’ preoccupations overlap, but their story lines occasionally intersect.

“Heartbroke” isn’t the stuff of bedtime stories, but it is embroidered with the stuff of American myth. People named Pretty, Vangie, Beulah, Chilly Willie and Maple who wear blue suede shoes and go to bars called Cadillac Flats and Seashell’s and make declarations like “tarnation,” who work at feed stores and buy things at the Dollar Disco. They occupy an unspecified era, mostly before computers and cellphones and the metaverse. It could just as easily be 1952 or 1989.

‘Other Resort Cities’ by Tod Goldberg

At particular moments, Bieker’s vignettes have the quality of a postcard sent by a Quentin Tarantino character, if that character grew up in Del Rey reading Flannery O’Connor and Annie Proulx. They run brothels and date miners named Spider Dick at improbably young ages, say things like, “Me, I’d been out turning grapes as far back as I could remember but by then I was fixing to marry and I had long red hair down to my waist and I was one sunburn away from old age.”

“Heartbroke” is not quite our world, but it is very much of our world. It’s a place where the myth of the West is inseparable from the deflation of the American dream — a water-thirsty landscape in which we are all left to pull ourselves up by the straps of our turquoise boots and continue on as gracefully as we can.

Pariseau is a writer and editor in New Orleans.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.