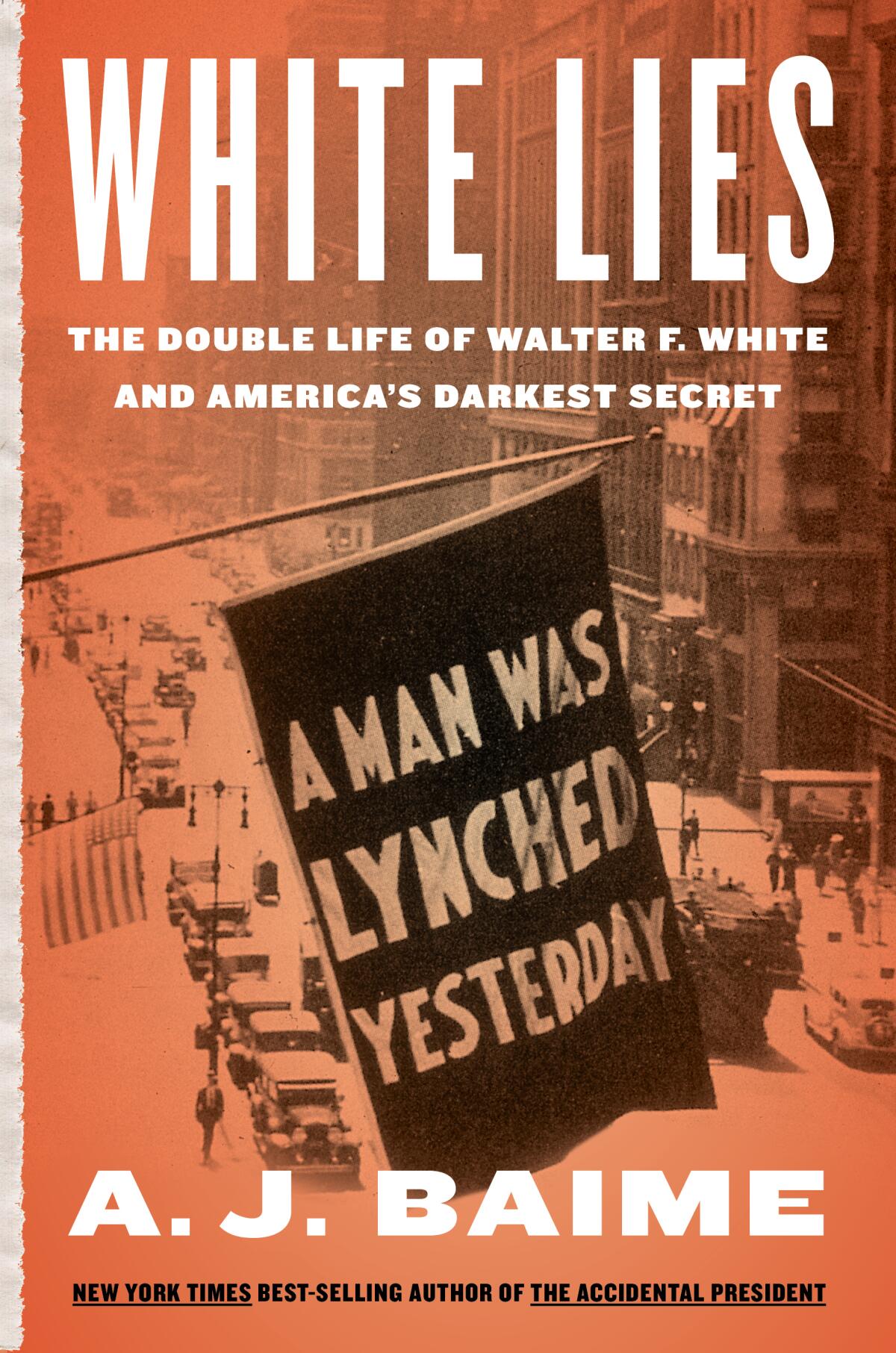

He risked his life to become a founding father of civil rights. Why was he forgotten?

On the Shelf

White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America's Darkest Secret

By A.J. Baime

Marine: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Mention Walter White and it will likely conjure an image of Bryan Cranston from “Breaking Bad,” playing the man who snarled, “I am the danger.”

But there’s a real-life Walter White who deserves to be a household name — a Black man who faced unfathomable danger in pursuit of truth and justice as he did battle with the American way. White should rank alongside Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X as a founding father of the civil rights era. Yet he is all but forgotten today.

That oversight gets an overdue correction in A.J. Baime’s engrossing new biography, “White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret.”

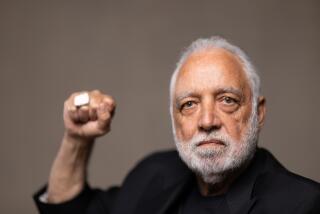

“Walter was the most powerful figure of America’s civil rights movement for this first half of the 20th century,” Baime says of White, who died at 61 in 1955, during a video interview from home outside Sacramento. “He was always going with the throttle fully down. That’s how he lived and why he died so young.”

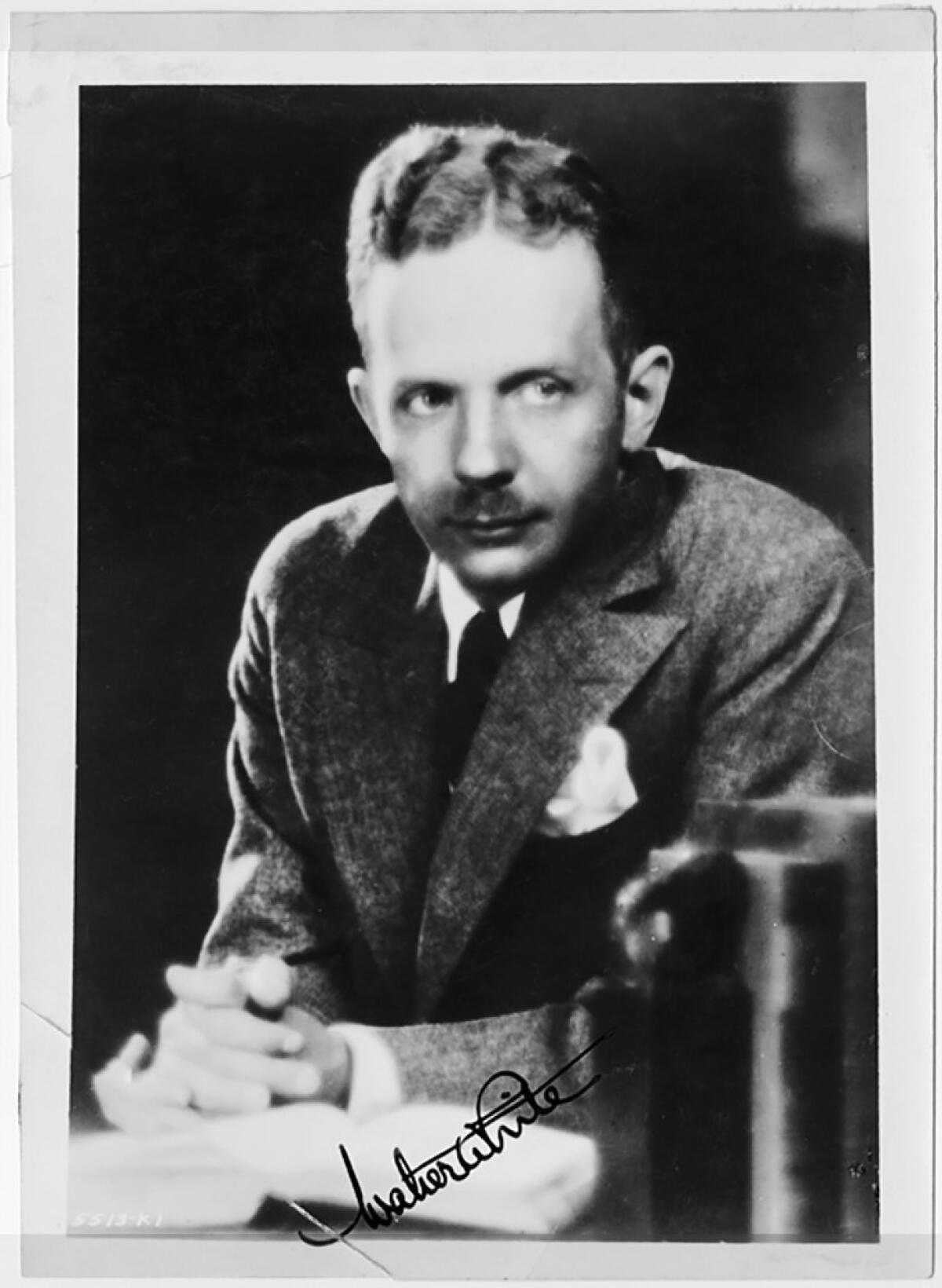

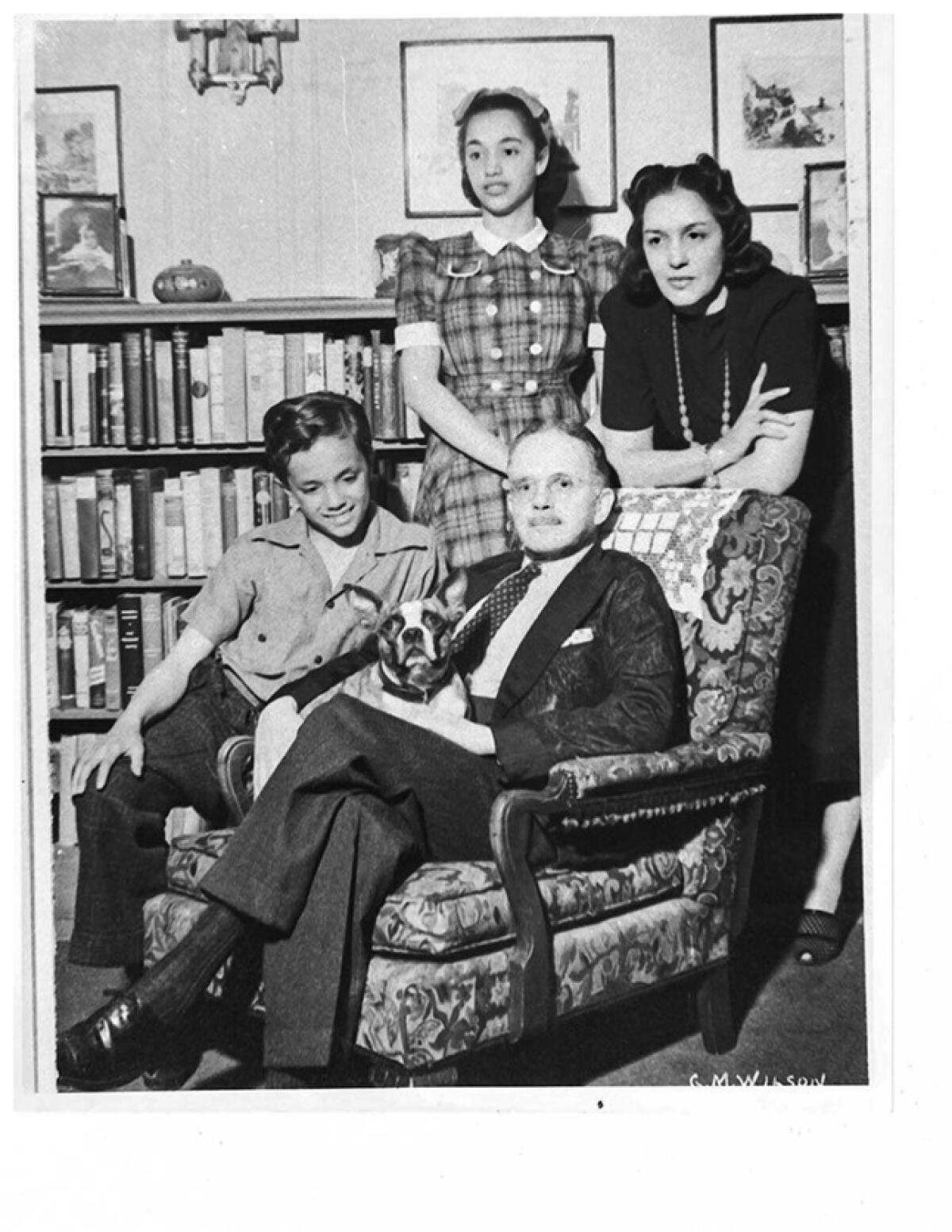

The double life of the title plays out several ways. Born in Atlanta in 1893, White was defined as Black by Southern laws and customs. Yet his enslaved forebears were raped by white owners, making him, according to family history, a great-grandson of William Henry Harrison. With fair skin, blue eyes and blond hair, he could easily have passed as white and ensured himself a better life.

Instead, White worked doggedly to force change. Baime depicts him as a superhero with a secret identity. In the 1920s he lived in Harlem as a Black man, taking on a crucial role in the fledgling NAACP while also fostering the Harlem Renaissance by nurturing Black artists like Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Zora Neale Hurston. He invited them to his high-profile parties, introduced them to white publishers like Mark Van Doren and Alfred Knopf. (His own books were also well received.)

That was only half the story, however. White also spent much of the decade traveling undercover in the South, passing as a white man so he could investigate lynching after lynching, gathering information to push for arrests (which rarely happened). If he’d been caught, he likely would have been lynched himself. “The investigations were making him famous, so every time he did it, it was even more dangerous,” Baime says.

In 2019, journalist Ben Raines helped find the Clotilda. He discusses his book, “The Last Slave Ship,” and the triumph and tragedy of its descendants.

In the 1930s, White shapeshifted from intrepid crimefighter to savvy political leader, spending more than two decades at the head of the NAACP. His fingerprints are on nearly every ladder-rung of political progress in that era. “He was clever, manipulative and very good at getting what he wanted,” Baime says.

White hired Marshall to lead the NAACP’s legal fights, helped arrange for Marian Anderson’s groundbreaking performance at the Lincoln Memorial. And, most notably, he orchestrated the shift of Black voters from the Republicans (the “Party of Lincoln”) to the Democrats by pressuring Roosevelt and Truman to take stands against the powerful Dixiecrats. Both presidents passed legislation against segregation and discrimination in the military and other fields.

“Black America was horrified when he first befriended FDR,” Baime says, “but he saw the shift happening before it happened. He was way ahead of the game.” Yet even while relentlessly pursuing a fairer, safer America, White still lived a bifurcated life. “He becomes the face of Black power,” Baime notes, “even though his skin is white, he is mingling in the white world’s high society, and he is secretly in love with a white woman.”

Baime, 50, came to White’s story gradually. After a small book about the history of liquor (“not particularly good,” he says) and one that was the basis for the film “Ford v Ferrari,” Baime turned his attention to presidents and politics, writing a book about Roosevelt and two about Truman.

White was a minor character in those books, but “I knew there was an amazing story that hadn’t been told in a mainstream way,” Baime says. (There have been two White biographies from small presses — one recent and one out of print.)

Baime admits to some ambivalence over being another white man telling a civil rights story, but he felt he could take it on because of White’s dual identity. “At the end he defines himself essentially as both [Black and white], which is what enabled me to do it,” he says.

Scott Ellsworth talks about ‘The Ground Breaking,’ a new follow-up to “Death in a Promised Land,” his pioneering 1982 exposé of atrocities in Tulsa.

Baime studied White’s papers at Yale University, then finished his research at New York Public Library and its Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, completing the work just before the pandemic shut down the world.

Given that White repeatedly risked his life in his battle to stop America’s sickening cycle of lynchings, his story felt particularly timely as the nation reckoned with the murders of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery.

White would know better than to buy the common refrain that “that’s not who we are as Americans”; he told us who we really were. Still, Baime believes he would be surprised and dismayed by the persistence of systemic racism: “He spent his career trying to turn America into a place where these kinds of things don’t happen. When he died he felt a lot of pride about the progress that was made during his lifetime.”

Baime also asks why White is forgotten today. His greatest fame preceded the ubiquity of television, for one thing. But he was also overtaken by the next generation. “Walter could see the movement splintering politically,” he says, adding that White opposed W.E.B. Du Bois’ Black nationalism and was “criticized by the far left for embracing the mainstream political system.”

It’s also undeniable, Baime adds, that followers of Malcolm X and the Black Panthers would never honor a man who looked white as “the foundation of their movement.” The last straw, he argues, was White’s divorce from his Black wife in order to marry his white mistress. “With all that, it wasn’t too hard for his story to disappear.”

Baime poured everything he had into remedying the erasure, researching horrific lynchings and wrestling with how much to include. “I cried every single day I wrote this book,” he says. “Not even my wife knows that. I run four or five miles every day, and I’d just stop and go, ‘Aagghh.’”

Even as a backlash brews over teaching America’s racist history, ‘Forget the Alamo’ and ‘How the Word Is Passed’ tell of the full, inglorious past,

He cried because of the horrors and the exhaustion. “But a big part of it was, his story moved me so much,” Baime says. “I don’t think there are many other people who could have accomplished what he did. That’s why it’s shocking people don’t know who he is.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.