Has China gotten the upper hand on Hollywood? A new book makes the case

On the Shelf

Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy

By Erich Schwartzel

Penguin Press: 400 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Changes in China since the 1990s have created the largest middle class on the planet, a market hungry for material goods as well as Western movies and TV shows. That was true for a while, but as in Hollywood, consumer habits in China are rapidly shifting. These changes are meticulously chronicled by journalist Erich Schwartzel in his comprehensive new book, “Red Carpet: Hollywood, China, and the Global Battle for Cultural Supremacy.”

China’s emergence coincided with Hollywood’s move toward big-budget franchises and a focus on foreign markets. As Hollywood wooed China, China studied Hollywood, courting veteran filmmakers to produce homegrown titles and give “master classes” on writing, acting and technical aspects of the medium.

In 2017, a Chinese-made, jingoistic action movie titled “Wolf Warrior 2” became the biggest hit in Chinese history, grossing $874 million. While U.S. imports languished, it was followed by other homemade blockbusters like last year’s “The Battle at Lake Changjin.” In 2020, at the height of the pandemic, China surpassed the U.S. to become the world’s largest box office.

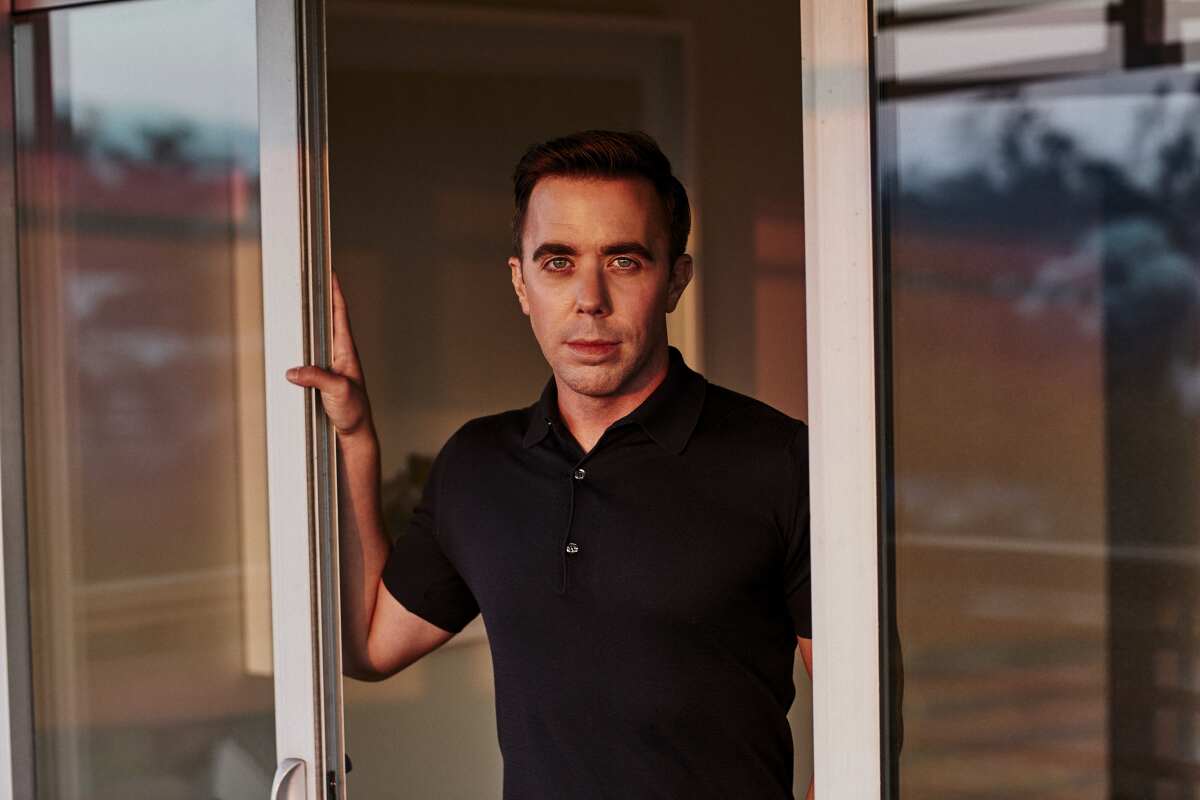

Hollywood producers have long struggled to navigate draconian and occasionally bizarre do’s and don’ts of conducting business in China, and in recent years have found fewer U.S. films are being admitted there. Schwartzel, a Wall Street Journal reporter, spoke with The Times about propaganda, censorship and the authoritarian playbook in a conversation that has been edited for length and clarity.

Recent comments by Trump administration officials have drawn renewed attention to Hollywood’s moves to placate Chinese censors.

As demand flags and fewer films are allowed entry, is the door into China closing on Hollywood?

I don’t know if audiences don’t want Americans there but it seems like the officials don’t. Not only are American movies not doing well but the big ones are not getting in at all. And it’s left a big fat zero in the China column on a bunch of big releases. What’s frustrating for Hollywood executives is there’s really no recourse. Chinese movies are making so much money. I’d imagine that it’s a case where if you want to see a Chinese movie, you go to the theater. If you want to see a new American movie, you just pirate it.

How do you account for John Cena’s bizarre taped apology for calling Taiwan a country?

That was apropos of needing to get “Fast and Furious” movies in the market, needing to make sure that Universal’s theme parks continue apace, and making sure that Universal’s agreement to distribute the Olympics [via NBC] was safe. It seems like a hastily made, rather bizarre videotaped confession, but it actually was trying to hold the glue together on much larger corporate interests.

Have executives become paranoid about doing business there?

They have reason to be paranoid. Over the past two years we’ve seen an incredible amount of scrutiny toward comments made or turns of phrases the [Communist] Party has deemed problematic resulting in real retribution. Some executives are looking at themselves saying, “What am I doing here? Am I really bending over backward to do business with a country I have to take a burner phone to?”

China, the world’s largest box office, is using its market power to influence Hollywood and project the Communist Party’s voice.

Netflix doesn’t do business in China, yet it seems profitable. Why don’t the studios follow its example?

The studios have become, over the past decade, almost entirely reliant on these big-budget theatrical releases. The priority at the studios are movies that can cost $200 million and require a global release to turn a profit. When you’re greenlighting another movie that’s going to run you $200 million, to justify that expense in a greenlight meeting, an executive should say we’re expecting X amount of dollars out of China.

Since the takeover, is the Hong Kong film business done for?

It’s the end of what you knew it to be. The idea that it would remain this cutting-edge, globally recognized creative and often provocative force isn’t the case anymore. We’ve seen a steady absorption of the Hong Kong industry that has complemented the steady absorption of Hong Kong itself. A lot of Hong Kong directors are being hired to make much bigger films on the mainland.

You compare Beijing with the Nazis when it comes to demands put on the studios.

Beijing is following a very similar playbook as the Nazis did before the U.S. entered the war. Germany made it clear that it would punish studios for making [anti-Nazi] movies even if those movies didn’t play in Germany, as China did with “Kundun” and “Seven Years in Tibet.” Neither film was released with expectation of playing in China and nonetheless got those companies in hot water. The other thing is the effort to control moviemaking at the preproduction stage, making it clear that if a movie moves forward it will be a problem. Lastly is a method known in China as “killing the chicken to scare the monkeys,” which means making a very public example of something you disagree with as a way to show everyone what will happen if you step out of line.

Chinese billionaire Wang Jianlin arrived in Los Angeles in October to a reception befitting a true Hollywood mogul.

Actress Fan Bingbing, who was detained and had to be green-screened into her recent movie “355,” represents a cautionary tale.

Fan Bingbing was one, Jack Ma was out of the public eye for a while and Peng Shuai, the tennis star, is the most recent one. Fan Bingbing was busted for tax fraud and disappeared for several weeks. To put it in perspective, it’s like if Angelina Jolie or Jennifer Lawrence just disappeared off the face of the Earth, no one knowing where she was and being afraid to even ask. What it did was kick off a broader effort by [China’s President] Xi Jinping to bring the entertainment industry underfoot.

Can Chinese propaganda win hearts and minds outside China?

It doesn’t seem likely that we’re going to have a Chinese blockbuster in the U.S. anytime soon. But I spent some time in Africa, where there’s an audience that is replacing the U.S. with China as its most visible superpower. Does it look like a wholesale replacement campaign? No, but it looks like something of a coexistence.

Can you contrast these Winter Olympic Games with the 2008 Beijing Games?

The contrast is great. In 2008, China was filling the role that the U.S. had played a century earlier. It was this new player on the world stage ready to announce itself. There’s been a complete erosion since. Instead it’s shining a spotlight on issues that have emerged with regards to human rights, freedom of expression, authoritarian behavior. Peng Shuai is one example, but the Uyghur camps in Zhejiang is a big one. And we cannot underestimate the effects of COVID and this pandemic that has clearly hurt China’s reputation. These games, rather than being a sequel to the 2008 ceremony, are instead going to be a conversation about what China’s rise has meant to these very important issues.

Politics have once again have thrust themselves into the Olympics and athletes must walk the line between social protest and the right to compete.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.