On the Shelf

Shaky Town

By Lou Mathews

Tiger Van: 240 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Every August for the last decade, Lou Mathews has vacuum-sealed chiles on his kitchen table. He will use them in recipes throughout the year, but the ritual has become something of a holiday: In the morning, he drives to Whittier and picks up bushels and bushels of peppers; by the afternoon, guests have arrived at his Beachwood Canyon home. They have followed meticulous directions Mathews has circulated over email, which include a history of the Hollywood sign, intricate alternative routes in case you miss a turn and a long excerpt from Nathanael West’s “The Day of the Locust.”

They all come, really, for what Mathews calls his “legendary toasted cheese sandos”: Between two pieces of soft white bread, he places a slice of Havarti on one side and Muenster on the other and packs the middle with chiles. He pairs the sandwiches with a rosé he seems to know intimately.

Mathews, 75, is a laborer who has always used his hands: in the kitchen, on a car engine, at his computer. A former street racer and mechanic, he is also a funny, generous and methodical person who, though praised as an almost mythical writer around Los Angeles, has not yet gotten his proper due.

He has written seven books, but until this year had published only two of them: “Just Like James,” a novella centered on a replica of James Dean’s crashed Porsche; and “L.A. Breakdown,” a lauded novel about street racing.

His third publication, “Shaky Town,” a novel of interconnected stories set in a fictional 1980s East L.A. neighborhood, arrived at the end of August, thanks in part to a mentee’s drive to cement his legacy. Jim Gavin, the creator of the critically acclaimed AMC series “Lodge 49” and a recurring guest at the annual chile celebration, said he owed a debt to Mathews “that has long needed to be repaid.”

The earthy eccentricities of AMC’s “Lodge 49” are inseparable from its success — or from the place, and people, it so memorably conjures.

In 2005, Gavin took a fiction-writing class with Mathews that he often references as a turning point in his life. Mathews encouraged him, Gavin says, to turn his gaze toward a place he knows best, the often-ignored pocket of Southern California where he grew up. After a short-story collection, “Middle Men,” Gavin shifted focus to TV.

When AMC canceled “Lodge 49” (in which Mathews made a cameo) after two seasons, Gavin was left with free time and money to spare. Partnering with Prospect Park Books and Turner Publishing, he launched the imprint Tiger Van Books. Its manifesto: “We believe in books. Our business model is failure. We plan to lose money and fold quickly.” “Shaky Town” is its first title.

It’s a story Mathews has been trying to sell for much of his adulthood. “I typically got two responses to the manuscript,” the author said at the August gathering, after he had finished making grilled cheese sandwiches for his family and friends. He sat in an armchair in his living room, sipping rosé. “They’d say, ‘This is good writing, but we don’t know what it is.’ Or they’d go, ‘This is good writing, but we can’t sell it.’ … In short, I was not giving them back the version of Los Angeles they prefer.”

That is a Los Angeles Mathews thinks New Yorkers want: a romanticized L.A. in which “one of their own” parachutes into town and explains the city to their pals on the East Coast. Mathews lives, instead, in the texture of the everyday, in the sounds and sights of the insular communities that make up most of his work: the granular process of cooking a tamale; the intricacies of betting on an illegal street race; the artistry of the men who constructed the highways. He writes for them, toward the outskirts.

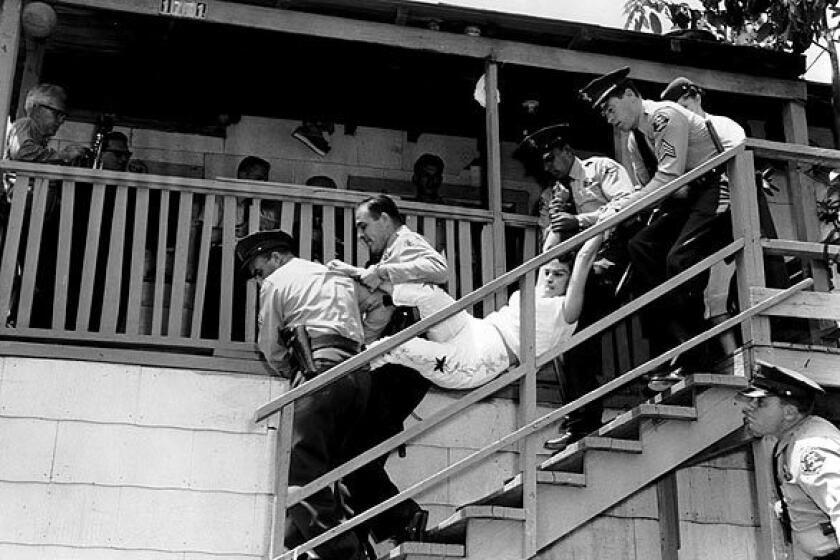

By way of example, he cited Tom Wolfe’s famous essay about a custom car show in Burbank, which appeared in Esquire in 1963. “I was there,” Mathews said. “He didn’t get everything right.”

Mathews has always been exhaustively busy. It wasn’t until he was 39 that he finally gave up — as he puts it — “twisting wrenches” for a paycheck. (He still fixes engines, sometimes as barter for artists’ paintings.) And it was only a few years later that he’d transform into a full-time writer, freelancing for local outlets like LA Weekly and the defunct L.A. Reader and then, at last, becoming an instructor at the UCLA Extension school.

He has taught there since 1989, guiding many of his students to a level of success that has eluded him. He has thus fostered an entire community — a neighborhood, like Shaky Town, of his own making. You cannot discuss the literary world in L.A. without mentioning Lou. To name but a few of his pupils: J. Ryan Stradal, Eric Nusbaum, Dana Johnson and, of course, Gavin. (The novelist Aimee Bender applied for Mathew’s class more than once.) All the while, Mathews has been quietly publishing fiction in some of the most esteemed literary journals in the country, such as the New England Review.

Eric Nusbaum’s “Stealing Home” follows a family displaced from Chavez Ravine, where Dodger Stadium was built.

“Lou was the first person to ever pull me aside and say that I had talent,” said Johnson, an award-winning author (“Elsewhere, California”) and USC professor who met Mathews nearly 30 years ago. He encouraged her to get a master’s in creative writing, a degree she wasn’t even familiar with. “I had never been told any of that before,” Johnson added. “He was very direct. It was very inspiring.”

Like his characters, Mathews remains a genuine, working-class man. He said he picked up golf, a notoriously nonworking-class pursuit, because he was “sedentary” and did not comprehend exercise without a somewhat practical purpose. (He plays only on municipal courses.)

In summary, Gavin said, “Lou’s work represents a kind of authentic working-class realism that is no longer in style, if it ever was.”

Mathews has spent much of his life in Los Angeles, with the exception of about 10 years up north — during and after college at UC Santa Cruz — and some low-residency graduate work at Vermont College. The people of Shaky Town, though, belong to Mathews’ adolescence in and around southern Glendale: A Korean store owner, Mr. Kim, buys a gun to ward off the local drug users who assaulted his wife; an art professor commutes home from his community college job, repeatedly stopping to pound tall boys as he reflects on his dying mother; a young woman tries to get her boyfriend out of jail, posing as his wife. (She channels the voice of an ex-girlfriend from the author’s youth.)

Mathews is most adept, perhaps, at capturing the mood and movements of a city in some ways as overlooked as he has been. “At sunset, with the orange light behind it, and with the speeding cars and huge trucks changing its shape on the millisecond, the interchange becomes monumental art, more complex and visionary than the earth art documented in museums,” the art professor narrates. “I always think they should let the architects sign the pillars.”

If there is a human through-line in the novel, it is Emiliano, the self-proclaimed mayor of Shaky Town, who gets four parts. In the opening chapter, he tells his life story and the history of the neighborhood to an unsuspecting man at a bus stop. He lost his son to polio, started drinking and then, intoxicated while on a carpentry job for the film industry, cut off three fingers with a table saw. “Whenever you see John Wayne break a chair over someone’s head?” he says to the stranger. “I built that chair.” It is the tale of a man telling stories — his stories, his truth — to whoever will hear them.

In one of the final stories in “Shaky Town,” “Last Dance,” a woman named Anita Espinosa throws herself a birthday party at the Community Center, “what they call the gymnasium at Coma Park now.” She has been Emiliano’s neighbor for more than 50 years. He had minor tiffs with Anita in the past that have evolved into major slights, but his neighbors badger him into going. He relents, in no small part because of the food he’ll be able to eat there. When the priest fails to show up, Emiliano acts as the host, giving an impromptu speech about his old friend. The music starts playing and the two of them waltz. Anita starts to cry into Emiliano’s shoulder, and you cannot quite tell if they are tears of joy or sadness.

It’s a lovely moment: You make sacrifices for your neighbors. And then they, in time, pay you back.

Norcia is a writer living in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.