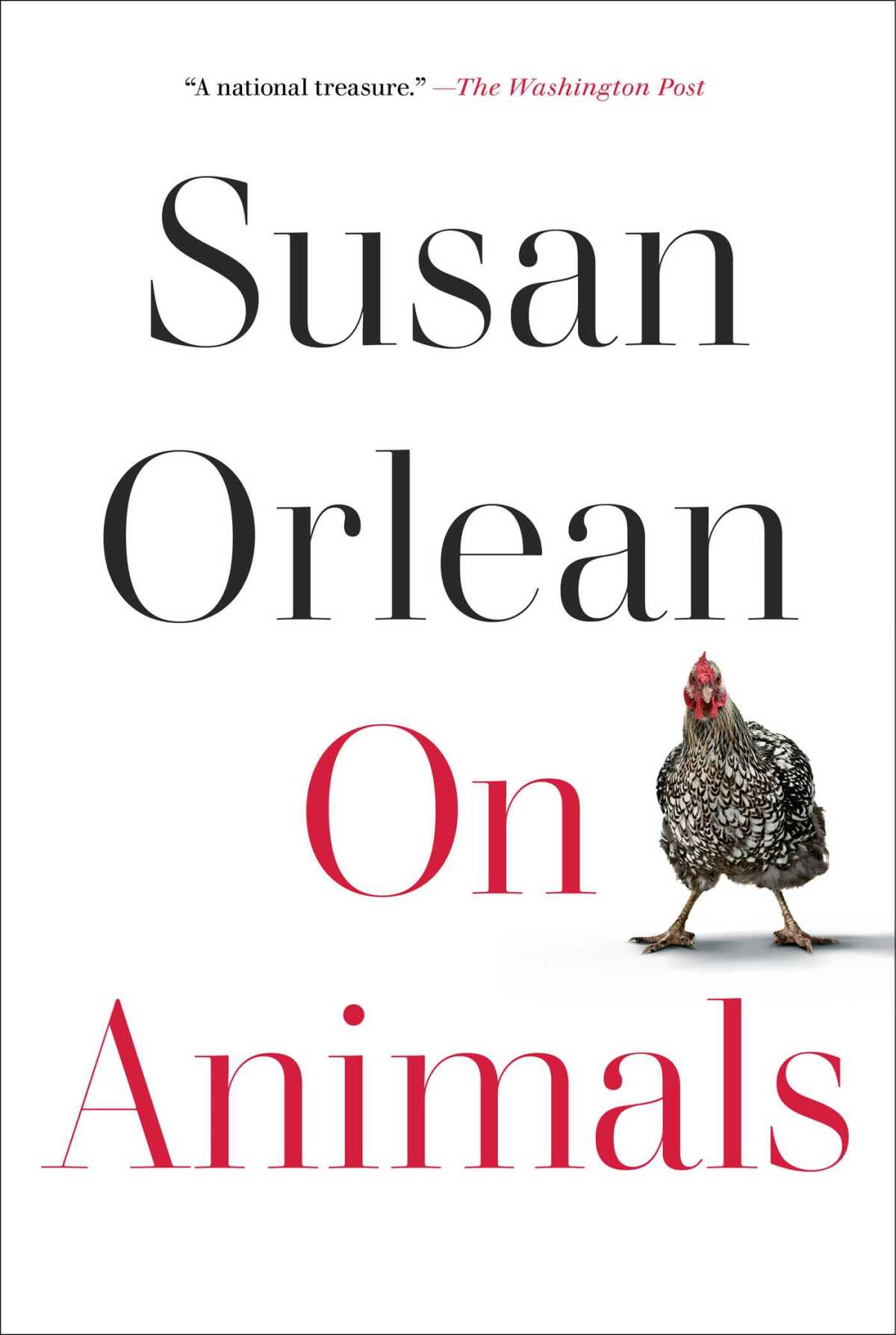

Susan Orlean’s new book explores our intense love of animals, especially donkeys

On the Shelf

On Animals

By Susan Orlean

Avid Reader: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

As a reporter, Susan Orlean doesn’t wear her love for animals on her sleeve. Who could afford to get overly attached in this cruel world? Baby tigers can be procured over the internet, the northern white rhino has been poached to extinction and a rabbit plague once wiped out 140 million bunnies in China. Orlean balances these hard truths with deep affection in “On Animals,” a companionable collection of her writing over the last two-decades-plus for the New Yorker, the Atlantic and other outlets on all manner of beasts.

No matter what else might divide us as readers and writers, the animal-human bond is one of the few relationships most of us hold sacred. Throughout the collection, Orlean meets some of the most devoted: An epidemiologist goes to great lengths to contact-trace her kidnapped dog; a Moroccan veterinary clinic treats every animal that comes to its door, including pack animals, for free. Sometimes reverence leads to folly. In “Where’s Willy?” about the famous orca (real name: Keiko) from the ’90s movie “Free Willy,” Orlean captures the absurd stunts humans will perpetrate to satisfy their notion of animal freedom. Absurdity aside, there’s no denying its beautiful ending: Keiko, swimming with his brethren, reimmersed in the wild waters near Iceland. (Cue Michael Jackson score.)

The part of Orlean who, as a child, wheedled her pet-averse mother into adopting a dog is never too distant from the scrutinizing reporter. “On Animals” is bookended by two diaristic essays that showcase the author’s animal-lover bona fides. She wrote a book on ’50s canine star Rin Tin Tin and long maintained a fowl-centric menagerie in the Hudson Valley. (And though it goes unmentioned, who can forget her demand for snuggles from her cat, Leo, her “drunk comfort animal,” on Twitter last year?)

Orlean’s deft handling of facts and her lived experience as an animal softy create a pleasing friction. It turns out that Orlean the pet owner is sentimental — supposedly a reporter’s bane — until reality intervenes. The first time one of her pet chickens is picked off by a predator, she reports crying for hours. By the fifth time, “I sighed deeply and went out and bought a new chicken.”

If you want to get Susan Orlean riled up, just ask her about the economist who suggested the government could eliminate public libraries and “save taxpayers lots of money” now that we have Amazon for books and Starbucks as a gathering place.

We need this kind of romantic-realist hybrid to guide us on this literary safari, which doubles as a travelogue. An incomplete list of locations: the panda forests of China, a wealthy Atlanta suburb, the oxen-tilled Cuban countryside, a taxidermy championship in Springfield, Ill., the plains of South Africa filled with frolicking lion cubs. In Orlean’s hands, no location indulges the fantasy of “nature.” She is a clear-eyed witness to how “almost all of the ‘wild’ spaces are managed in one fashion or another, and in South Africa, in particular, everything is fenced, and all animal populations are metered.”

Interestingly, of all places, it’s Los Angeles, where she moves in 2011, that impresses her with its multitude of free-range animals. In addition to spotting hawks, coyotes and bobcats, Orlean is taken with one of the city’s most famous residents: “That first winter, the lion known as P-22 took time off from managing his busy social media accounts and set up camp in the crawl space under a house not far from us. … We were in the second-largest city in America, and yet it felt like we’d moved into a natural history diorama.”

The animal kingdom may be as corralled as we are, but it’s also “alien, unknowable, familiar but mysterious.” Orlean acknowledges the mystery but doesn’t explore it. Instead, she relies on her powers of observation, conveyed with unflappable curiosity. Her rich storytelling is almost soothing, even when it’s about something as disturbing as South African hunting facilities sedating animals so they can be more easily shot. Sometimes I wished for more countenance with that unknowability — and perhaps our reluctance to think of ourselves as two-legged animals — but philosophical rumination is not included on this tour. Orlean is committed to investigating the dizzying multiplicity of roles animals serve — employee, best friend, harbinger of climate change — and the places where those functions intersect.

Susan Orlean went on a drunken Twitter whirlwind Friday night — or was it real? Here’s what the author tells us about her Twitter escapade.

One of the finest essays to probe that fuzzy middle ground is “The Lady and the Tigers,” from 2002. When a tiger saunters through Jackson, N.J., two entities are blamed for the escapee — a local Six Flags and the permitted, private operation known as Tigers Only Preservation Society, run by reclusive Joan Byron-Marasek. She claims the big cat wasn’t hers, but the publicity from the case exposes her operation as an alleged front for her illegal ownership of a dozen-plus tigers. As Orlean chases the twists and turns of the legal case, she tracks Jackson’s evolution from rural outpost to a full-blown suburb whose condo-dwelling residents don’t want roaring, deer-carcass-chewing neighbors.

“On Animals” is at its best when all Orlean’s strengths work in tandem — and it’s her adoration of the lowliest worker that elevates it most of all. In “Where Donkeys Deliver,” she marvels over the beasts that ferry all manner of supplies in the medina, the walled city within Fez, Morocco, whose narrow alleys cannot accommodate cars or motor bikes. Watching a donkey haul six color televisions strapped to its back, she writes, “I caught only a glimpse of the animal’s face as he passed, but it was, like all donkey faces, utterly endearing, managing to be at once serene and weary and determined.” It’s not long before she’s “fallen in love.”

Later, a donkey vendor at a market tries to pressure Orlean into buying one. She explains that she doesn’t live there, so a purchase would be impractical, but he presses on until a crowd forms around them. Most of us would try to extract ourselves from this situation as soon as possible, but Orlean just patiently explains her predicament. It’s one of the few times when practicality seems to win out over love, if only for a moment. Otherwise, Orlean is like the rest of us, devoted to creatures who are ornery, slobbery, aloof or just plain mortal when we don’t want them to be. As she writes in her final essay, regarding a death in the family, “even though dogs break your heart, they fill it up, even when they’re gone.” Orlean is still thinking about that donkey. Next time, she might make the leap.

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.