Review: A symphonic new story collection plays variations on New Orleans in all its masquerades

On the Shelf

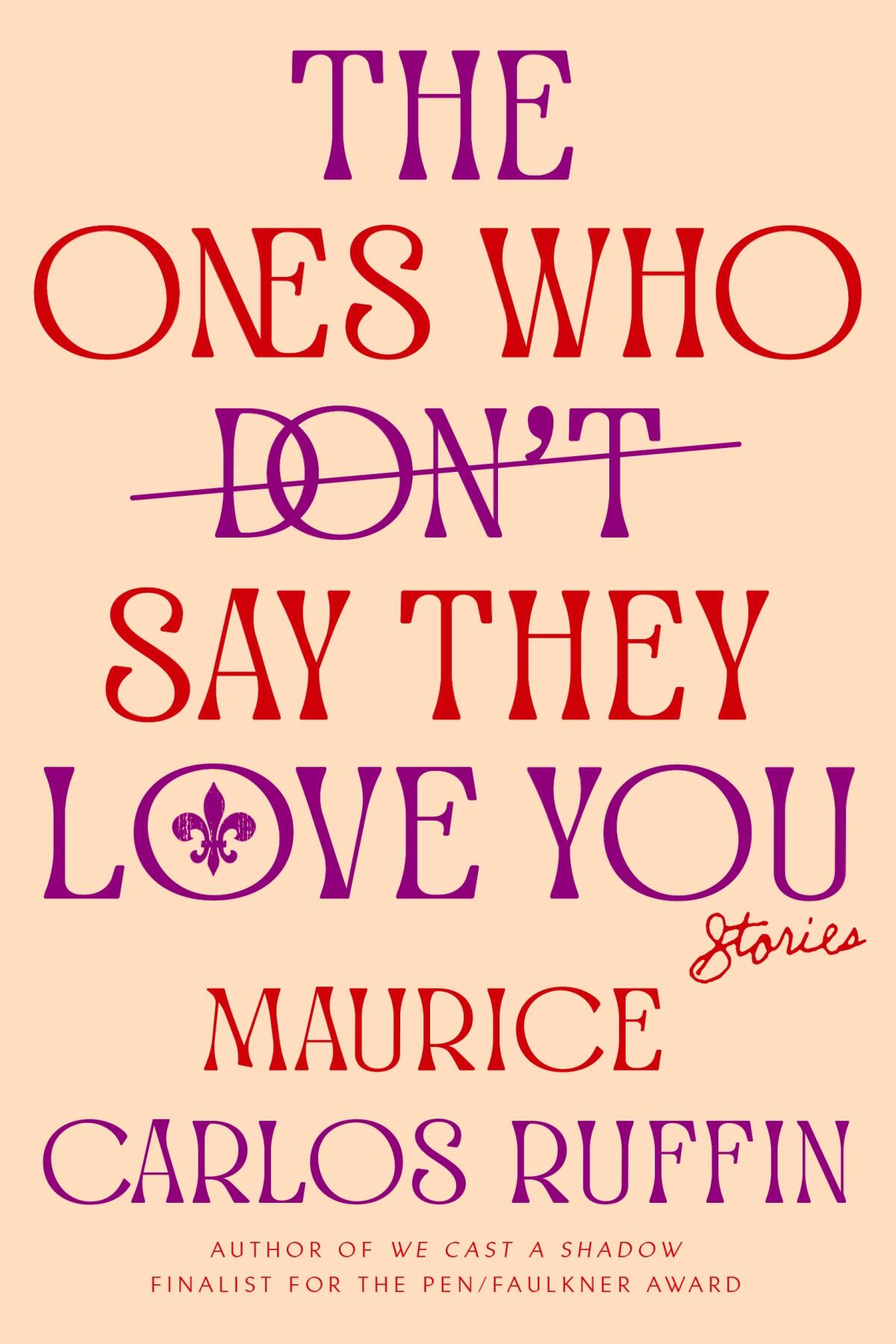

The Ones Who Don't Say They Love You: Stories

By Maurice Carlos Ruffin

One World: 192 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

If you’re looking to test the truism that writers choose fiction because no one would ever believe the truth, consider New Orleans. The fabulistic, near-mythical city presents a staggering challenge to those who would capture it in believable prose. This would explain why native son Maurice Carlos Ruffin chose to set his 2019 debut novel, “We Cast a Shadow,” in an unnamed Southern town.

In that speculative, satirical novel — dazzling and unsettling, channeling Vladimir Nabokov and Ralph Ellison — an unnamed Black lawyer aspires to give his biracial son the dubious gift of de-melaninization. Setting aside a specific location, Ruffin freed himself to rattle expectations of race and class without complicating his narrative with an exegesis of what he once called “the most unwieldy city in America.” By veiling the setting, he explained in an interview, “I was able to deploy all my best techniques and have a sense that they would actually work.”

His second book, a collection of short stories and flash fiction, drops the ruse. It begins with the title — “The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You” — which evokes New Orleans’ motto, “The city that care forgot.” The city’s trademark fleur-de-lis is even stamped on the book jacket. And rather than circumvent the facts and clichés of NOLA, Ruffin tackles them head on with a broad array of people and circumstances.

Several recent story collections (Bryan Washington’s “Lot” and Dantiel W. Moniz’s “Blood Milk Heat” spring to mind) present geographies as characters. While Ruffin’s stories can’t help but transport the reader to humid, sunken, decaying New Orleans, it’s too easy to say this book is merely a set of love songs to the city. What makes such collections ring true is the way they subvert conventional knowledge.

“Memorial,” Washington’s followup to his acclaimed story collection, “Lot,” pays homage to Houston, Osaka, and the bonds of unconventional family.

For too long, tourism has been a shorthand for worldliness. While mass and social media offer a superficially cosmopolitan perspective on global culture, writers like Ruffin reveal that travel is often less about cultural immersion than blithe escapism. What’s appealing and exotic about destinations like New Orleans masks a larger truth about the history and ongoing social problems that plague these places.

Fiction can reckon powerfully with such uncomfortable realities, but in different ways. Where novels offer an expansive canvas to flesh out injustice and unsung culture, stories are pressed to do more with less — to compress and layer and leave traces of what remains unwritten. Time and again, Ruffin constructs a life’s history in the space of a page or two. His skill as a writer and his birthright as a New Orleanian equip him for the task.

Masquerading is a way of life in the city, even outside Carnival season. If there’s a quintessential New Orleanian, it’s a chameleon, swapping one personality or persona for another. Distinctions between sinners and saints are muddled throughout Ruffin’s book, excusing him from casting judgment on his characters. In the title story, tap dancers scramble for tips but find better money in convention-attending johns. One street-corner hustler discovers unexpected concern and honesty from the one man who won’t say he loves him.

In “Ghetto University,” an unemployed professor of Russian poetry, facing eviction, trades teaching for mugging tourists in the French Quarter. With biting humor, the professor twists logic to justify his side hustle: He’s providing his “benefactors a valuable service. How so? Ever had a health scare? A near-fatal car accident? Knowledge that a plane crashed and you survived only because you missed your flight? Invariably, I imagine my supporters are much happier for having been graced by my presence. … Having not died together, perhaps they will live together. All thanks to moi.” His rationalizations fall short at a critical moment, shattering his brittle illusions.

Ruffin draws particular attention to ragged, flawed and unexpected relationships. There are parents and sons, thwarted lovers and marriages on the brink, gender-queer teens looking out for one another during the pandemic. And the task of rebuilding homes and lives in a city still scarred by Hurricane Katrina remains an urgent concern. Ruffin zeros in on haphazard, sometimes ad hoc families who have lost everything but their human ties.

In “The Yellow House,” Sarah Broom offers an intimate portrait of New Orleans East, ignored and neglected long before Hurricane Katrina.

In the story “The Pie Man,” 14-year-old Baby lives with his mother in the front half of a house damaged by Katrina’s floods. The Pie Man, a former Marine who may or may not be his father, espouses wisdom such as “A man has got to grab his own future for his own self.” Though he’s talking about disaster cleanup, his advice later spares Baby from a horrifying brush with brutality and mob behavior.

The story shares DNA with William Faulkner’s “Dry September,” in which a lynch mob attacks a Black man. Here, a group of young Black men bent on revenge wrongly target a Latino mechanic. It’s a chilling morality tale about many unintended effects of justice diverted and displaced anger gone awry.

Ruffin’s first career as a lawyer offers some insights into the role justice plays in his work. His analytical mind has revealed itself in nonfiction pieces published in literary journals, on gentrification, white nationalism and other threats to the communities he loves. But as with any true New Orleans artist, the message transcends Ruffin’s various mediums; up-tempo or blues, the song remains the same.

Indeed, for all of Ruffin’s clear literary homages and influences, there are also, I sense, musical structures embedded in these intimate, often playful stories. The pieces function as movements on a theme, each touching different notes and neighborhoods. A sense of controlled improvisation allows him to lay claim to his city without resorting to either satire or pseudonym. It makes his book achingly truthful and incredibly accessible.

In “Glamour Work,” a piece of flash fiction just over a page long, a young man on juvenile probation finds himself assigned catering work. After catching a glimpse of New Orleans royalty, he remarks, “I wish I could have told my boys the truth about everything I’d seen at that gala, all those people just living, but I knew they wouldn’t get it.” Ruffin knows that sometimes simply telling the truth isn’t enough to make a world familiar. It takes a chorus of stories, chaotic and loving, to bring a city to life. In this penetrating and energetic collection, as in the city it honors, the rhythm is as important as the details.

In travel writer Richard Grant’s “The Deepest South of All,” Natchez, Miss., is full of characters, stubborn racist traditions and lots of contradictions.

Born and raised in New Orleans, LeBlanc is a writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, N.C.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.