How a novelist cracked the real-life story of her Nazi-fighting ancestor

On the Shelf

All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days: The True Story of the American Woman at the Heart of the German Resistance to Hitler

By Rebecca Donner

Little, Brown: 576 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When author Rebecca Donner learned that a 89-year-old man named Donald Heath Jr. was alive in California, “I got on a plane immediately,” she says.

For the record:

11:20 a.m. Aug. 19, 2021This article has been updated to reflect the fact that Mildred Harnack passed information to an American diplomat for the COI, not the OSS; that Georgina was her mother; and that Egmont Zechlin, not Anneliese, memorialized Mildred’s arrest.

Heath, the son of an American intelligence operative, had been a courier for a German resistance group in Nazi Berlin. Donning a borrowed Hitler Youth uniform for a disguise, the 11-year-old boy would carry coded notes in his blue knapsack. If he suspected trouble, he would whistle a Nazi party anthem as a warning.

This gave him a personal connection to Donner — and gave Donner a way forward on a book she’d been hoping to write for decades. Heath had worked with Donner’s great-great-aunt, Mildred Harnack, a woman Donner never met but whose legacy she carries close to her heart.

“All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days” is Donner’s first work of history and a deeply moving act of recovery. After marrying German economist Arvid Harnack, Mildred moved from the Midwest to Berlin. When the Nazis took power, the Harnacks worked secretly against the regime until they were executed on Hitler’s direct order.

Novelist Donner (“Sunset Terrace” and the graphic novel “Burnout”) was determined to tell her ancestor’s story but stymied for years by a lack of source material — until she found Don Heath. “One of the first things Don said when we met was, ‘Oh, I remember your grandmother. She’s like family to me. So is Mildred. And so you’re my family.’”

Heath vowed to tell her as much as he could remember, Donner says, but he died soon afterward, a month shy of his 90th birthday. He didn’t leave her empty-handed, though. After his death, his family shared 12 steamer trunks of family archives, including his mother’s diary, “which helped me pinpoint the days when Don went to see Mildred for ‘tutoring’ and the days when the Heaths took their forest walks with the Harnacks. The story kept getting bigger and bigger.”

Philippe Sands’ ‘The Ratline’ is a Nazi-hunter novel with a unique premise: Sands tries to prove to the Nazi’s son that his father wasn’t a ‘good Nazi.’

Speaking via video from her home in Brooklyn, Donner — who grew up in Santa Monica — moves across her office, crowded with research materials, to retrieve a large white binder containing copies of Mildred’s letters.

Mildred’s sister Harriette, Donner’s great-grandmother, had had all her own papers burned. “She was no doubt terrified of a scandal,” says Donner. “Thank goodness her mother Georgina had a cache of the letters in her attic.”

The interviews, diary and other materials “allowed me to connect a lot of dots,” says Donner. She hadn’t wanted to write a memoir about trying to find Mildred; she wanted to actually find Mildred. The papers helped her expand outward from there, reconstructing the web of support and intrigue that constituted the German resistance. “I just thought, ‘This is not my story. It’s Mildred’s.’”

And what a story. Many accounts of Mildred and Arvid Harnack describe him as a scholar and her as “an English teacher” or “housewife,” but this is inaccurate. Arvid Harnack did have a PhD, but he essentially worked as a bureaucrat in the Reich Ministry of Economics. Meanwhile, Mildred taught American literature at the university level and eventually earned her PhD from the University of Giessen.

Mildred often appears in historical documents as one of the most visible and prominent American women in Berlin. Yet like her courier Don, she was playing a role, hiding in plain sight. At a time when the U.S. and Soviet secret services were wary collaborators, the Harnacks, both committed Communists, worked for them both; Arvid was an agent for the Soviet NKVD (precursor to the KGB), while Mildred passed information to a diplomat who would join America’s COI (which spawned the CIA).

It was hard to get their stories straight — very much by design. Arvid, the Soviet informer, joined the Nazi Party, using the “Heil Hitler!” salute as necessary. Mildred looked the part of the American, Nazi-sympathizing socialite. As Donner points out in the book, Mildred joined the Daughters of the American Revolution because she knew the Nazis would approve of its bloodline requirements.

Donner says she was careful not to speak for Mildred or presume to understand her motives. However, “In reading the letters she wrote to her mother, I have the sense that she was at times quite lonely as an American woman in Berlin,” especially once the American Embassy was cleared out and few fellow Americans were left in the city. “That’s when she turned to espionage for the Americans.”

Naomi Hirahara’s “Clark and Division,” set in Chicago, shines a light on the little-known aftermath of internment. It’s a crime novel only she could have written.

The author was so concerned about conveying the nuance in her research that she insisted on recording the audiobook herself. “An audiobook listener can’t see quotation marks,” Donner explained, “but the reader who records it can give subtle voice inflections to indicate emphasis — or you raise your voice a little to call out a headline.”

One subtle touch from a primary source still gives her goosebumps. In August 1942, knowing they would soon be arrested, the Harnacks fled to Lithuania, hoping to find safe passage to Sweden. Their hosts, Egmont and Anneliese Zechlin, were close friends, and Egmont wrote up an account of the moments after the Harnacks were captured by Nazi officers.

“Egmont mentions that there was a vase of flowers on the kitchen table Arvid had given to Mildred, and that just before they seized her, she stared at the flowers, smoothing the tablecloth beneath them,” Donner says. She swallows hard, imagining it. “We can’t know what she was thinking. I hope she was placing those flowers into her memory for the days ahead.”

Arvid was hanged in December 1942, Mildred executed by guillotine the following February. Before his death, Arvid wrote a two-page letter to Mildred that miraculously survived the war. But the only prison writing Donner has from Mildred are a few lines of Goethe that she translated in her cell:

“In all the frequent troubles of our days / A God gave compensation — more his praise / In looking sky- and heavenward as duty / In sunshine and in virtue and in beauty.”

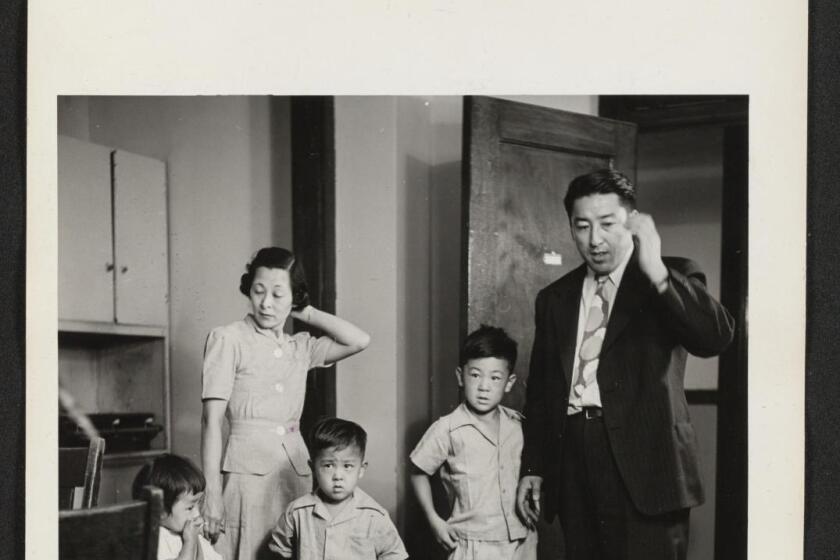

In a photo of those pages reproduced in the book, Mildred Harnack’s cramped yet careful handwriting crystallizes Donner’s goal: to write her heroic forebear back into history, to bring her back to life.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.