As bookstores struggled with COVID-19, this Culver City shop was just opening

Reaching for a metaphor to describe what it’s like to launch a bookstore during a pandemic, Jennifer Caspar alights on the parable of the frog in the pot of water — the one that doesn’t notice it’s being gradually boiled alive.

“In the beginning of the pandemic, I was like, ‘Oh it’s just going to be six weeks and then things will be back to normal,’” Caspar, 54, recounted on a gloomy afternoon outside her Culver City bookstore, Village Well Books & Coffee, which opened its doors in January, L.A.’s worst month of the pandemic. “I never really questioned it, I just kept moving forward.”

She had a bookstore to open. She never panicked.

After a brutal year of economic uncertainty, booksellers in L.A. are expecting a full recovery. But the June 15 reopening is reigniting safety concerns.

To use another waterlogged metaphor, she was swimming against the tide. For much of the past year, booksellers in Los Angeles and beyond have been contending not with startup logistics but instead a slew of economic hurdles and existential crises induced by the pandemic. Sales dropped 50% to 70% for many local bookstores. Some resorted to online fundraisers and public pleas for support. Many depended on the sales flood of the holiday season to get them out of the red, only to see it coincide with a massive surge in COVID-19 cases and a return to full shutdown. Some, such as Family Books on Fairfax Avenue, didn’t make it.

Caspar, in the meantime, was just getting started.

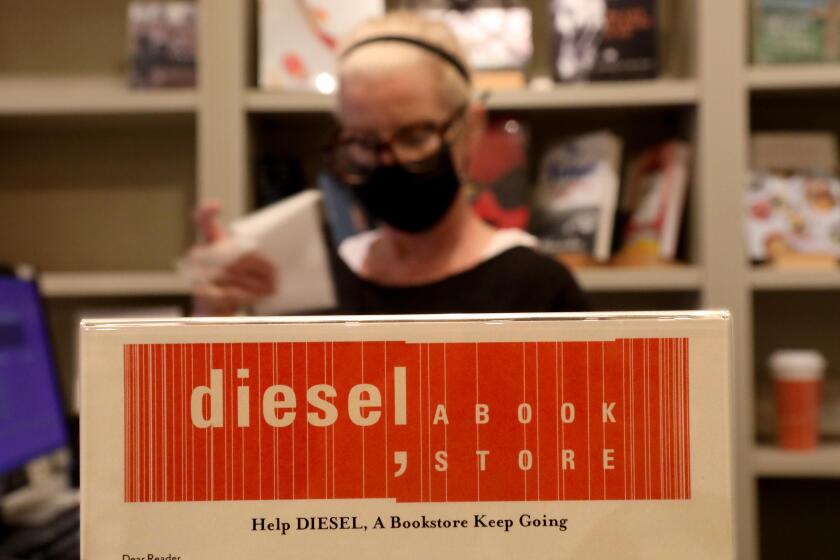

Beloved L.A. bookstores like Diesel are turning to fundraising platforms to survive the financial blows dealt by COVID-19.

After a years-long search for the perfect location, she found it in November 2019 on the star-crossed corner of Culver Boulevard and Duquesne Avenue, next to Culver City Hall. (The vegan joint Doomie’s struggled to attract customers and was forced to close — joining so many ill-fated predecessors that locals took to calling it the “doomed corner”).

Caspar signed a lease in February 2020. Conversations with architects were ongoing and city permits were in motion when the shutdown arrived, slowing an already drawn-out process. Having worked in community development real estate, Caspar knew that projects always take longer than you think, even in normal times.

After signing the lease, she projected a May or June opening, but in the back of her mind, she knew there was “an excellent chance” that wasn’t going to happen.

“It was frustrating because you’re always pushing for that sooner date… the [month] kept creeping back but it always felt OK,” she said.

But Caspar had a financial cushion — life insurance proceeds from her late husband — and the presence of mind to focus her efforts on a website. Even as many existing bookstore owners were ramping up online operations just to survive, Caspar was building one while her physical shop was still a construction site. Last summer, she posted banners around her store-in-progress, directing customers to the online shop. In May, she started selling books from her home.

Dozens of boxes of books, totaling some 1,500, spilled into the hallway and filled her daughter’s room and her guest bedroom. With her two daughters and some friends, Caspar drove as far as Burbank, Altadena and Torrance delivering books door-to-door.

Revenue grew every month and when the holiday season arrived, it skyrocketed. “In December, the orders were so crazy and exhausting,” Caspar said. “It was a lot of working nonstop, but it was enjoyable. It was great seeing it come together.” She started paying rent in November, had a soft opening on New Year’s Eve and officially opened Jan. 2 — with restricted capacity, of course.

Family Books is latest L.A. seller to fall victim to the pandemic

“Jen had the tenacity and foresight to stick with it,” said Joseph Miller, the owner of the building that houses Village Well. “She never wavered in her vision, and we worked together on rent so that it was financially feasible.”

Opening a bookstore during a pandemic turns out to have some upside. Without a physical site, there was no staff to pay or rent to worry about, and no partial reopenings, curbside pickups, emergency lockdowns or competition for loans and grants.

Still, even as cases surged in December, Caspar felt she couldn’t wait. And she knew how to adapt after watching other stores go through it. “I grew into it as all these new conditions were being revealed,” she said, “and then I opened my doors at a time when people are starving for in-person connections.”

Pandemic aside, she always knew that — “doomed corner” or not — opening a business was an ambitious pursuit. That’s why it took some 30 years to transform her entrepreneurial dream into reality.

Caspar and her husband, Eric Altshule, were in their 20s when they first fantasized about buying and running a public space — first an old movie theater, then a coffee shop that could function as a conversational salon.

Growing up in a small town in Connecticut, Caspar craved the opposite — a sense of bustle and community. She channeled her big-city aspirations into a career in urban planning and affordable housing. Altshule transitioned from Capitol Hill — serving on the staff of several Congress members — to working for his dad’s garment company. He died in 2010 of what was likely heart arrhythmia.

Caspar entered a period of grief and transition. Using the life insurance proceeds, she cut her hours to part-time, joined the board of the Skid Row Housing Trust and started a scholarship fund for children in her husband’s memory. The work she was doing “enabled me to really put thought into what this business would be,” she said.

Jane and Raymond Wurwand commit $1 million in grants to support small businesses in Los Angeles County struggling to survive COVID-19.

A year and a half later, Caspar went to a psychic.

“He’s saying you should do it,” Caspar remembered the psychic saying.

“He never wanted me to do it in real life,” she responded.

“But things are different now,” the psychic said, “and you have all the resources, you have everything you need, and once you start it everything will fall into place and you have people in your life and you know what to do.”

“From that minute on, I was like ‘I’m going to do it,’” Caspar said.

She did — and for all the tragedy in her life and in the city, she considers herself fortunate. “The timing has been very lucky for us. Just to be able to open slowly is such a gift... I’ve been able to figure it out step by step.”

Inside the bright and colorful 3,000-square-foot bookstore, art from local artists hangs on walls and shelves. A 20-foot mosaic mural showcasing Culver City landmarks sits in front of the coffee bar. The mural was designed and assembled by Piece by Piece, a nonprofit that provides low-income and formerly unhoused people with free art workshops. (Every month, the store highlights a different social cause with reading lists and links to supportive organizations.)

On a recent morning, Patrick Meighan sat cross-legged on an orange Adirondack chair in front of the bookstore, reading Michael Lewis’ “The Premonition.”

Meighan, a 48-year-old writer for “Family Guy,” was walking by the store late last year when he was shocked to see a “Coming Soon” sign at the “doomed” corner. “I just couldn’t believe that in 2021, in the middle of a pandemic, somebody was opening a local bookstore,” he said. “It just seemed like something from a forgotten era.”

It’s why he fell in love with the place. “To open an independent bookstore in the middle of a pandemic is just such an act of stupid optimism and such a vote of confidence against all odds in civil society that I was like, ‘I love that, I want to support that,’” he said.

He’s walked to the bookstore almost every morning since the opening; an unlikely pandemic discovery has become part of a happy post-reopening routine. Meighan reads and drinks coffee until he tells himself: “All right, time to go write some fart jokes.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.