Review: What lawmakers should know about the first Federal Writers Project. (It was a glorious mess)

On the Shelf

Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover America

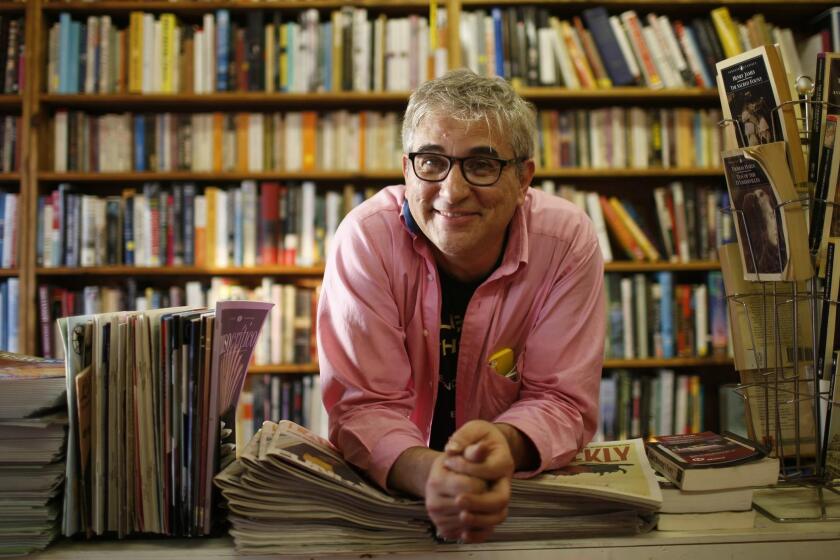

By Scott Borchert

FSG: 400 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

For a few years during the Great Depression, the federal government paid writers to write. Novelists, poets, journalists, teachers, librarians, ministers — pretty much anyone who could put a sentence together (and some who couldn’t) got a paycheck for producing hundreds of publications that captured the highways and folkways, history and zeitgeist of America.

Though it saved some of the country’s most talented authors from starvation, the Federal Writers Project had a short life. Targeted by anti-Communist crusaders and budget slashers, the FWP expired during World War II. But now it’s 2021, and after a year of Covid-19, many organizations that support writers are on life support. Could the writers project rise again? Rep. Ted Lieu, D-Torrance, thinks so, and has sponsored legislation that would revive a version of the FWP. He would do well to read Scott Borchert’s engaging new book, “Republic of Detours,” a lively chronicle of the rambunctious years of the FWP.

Borchert begins his story with Henry Alsberg, a writer, playwright, foreign correspondent and international relief worker with the looks of “a loveable Saint Bernard” who became the FWP’s first director. Alsberg helped shape the organization, which at its peak employed about 4,500 people and produced hundreds of publications, including a groundbreaking collection of oral histories from former slaves.

Congressman Ted Lieu introduced the 21st Century Federal Writers’ Project act on May 6. It all started with an article by David Kipen in the L.A. Times.

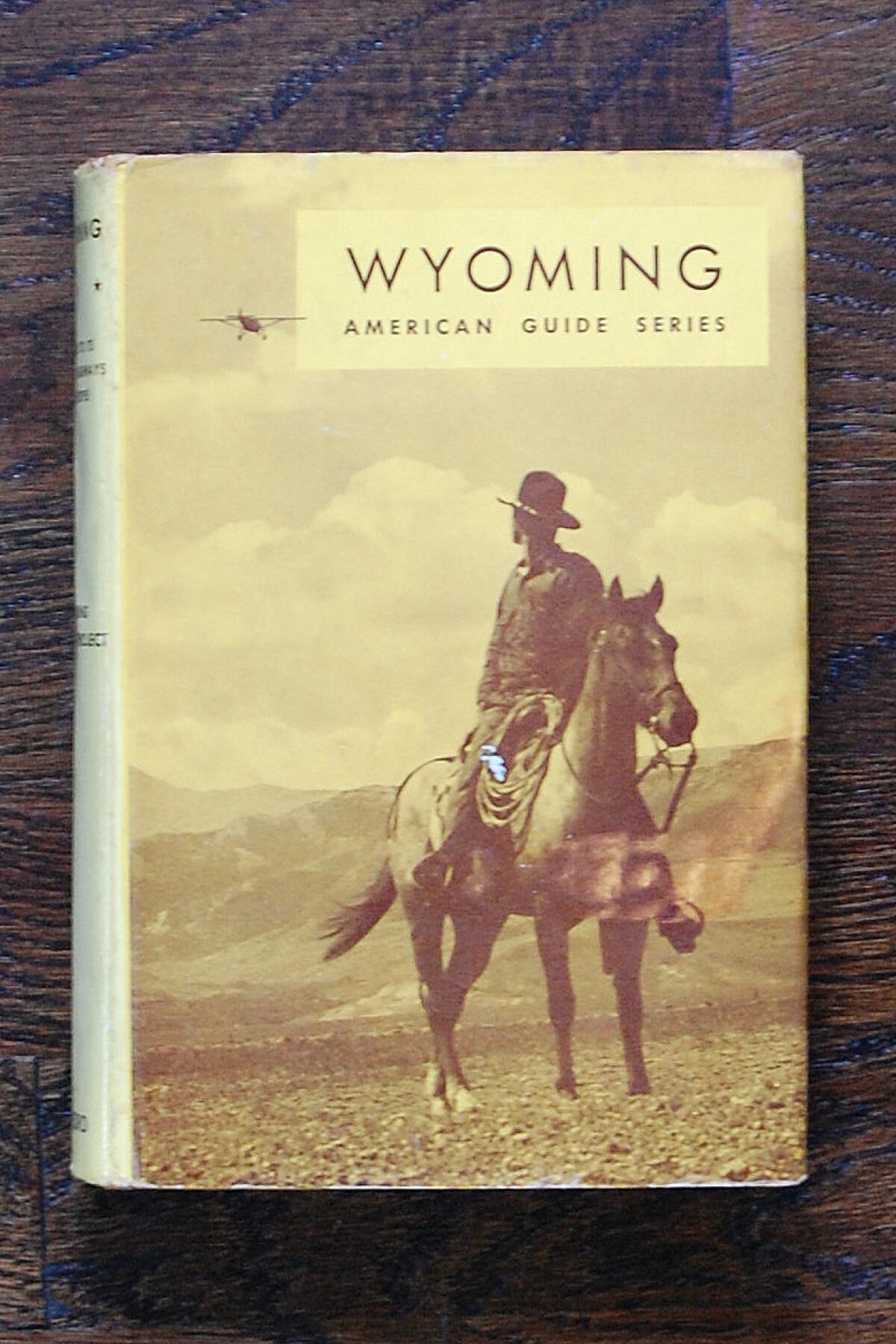

But its main brief was to produce a series of American Guides, one for each state. They were conceived as a way to document local history and promote travel, but morphed into “a mélange of essays, historical tidbits, folklore, anecdotes, photographs, and social analysis — along with an abundance of driving directions thickened by tall tales, strange sites and bygone characters.” In short, writers were given a very long leash. They mostly worked from state offices with patchy supervision, and the quality of their work vacillated from inspired to insipid to just plain awful.

Vardis Fisher personified the challenges of supervising a bunch of writers in an age before the internet. The son of Mormon homesteaders and the apotheosis of rugged Western individualism, Fisher was chosen to run the FWP’s Idaho office and instructed to hire local researchers and writers to chronicle the state’s history, folkways and superstitions. Fisher, convinced no one could do it as well as he could, wrote almost the entire guide . Editing him was an ordeal: “Alsberg wrote to Fisher to remind him that it was unacceptable for the guidebook to point out which towns were ugly, even if it was true.” Despite or because of Fisher’s bullheadedness, the Idaho guide, the first one published, received rave reviews from historians on the order of Bernard DeVoto.

Other writers used the FWP to launch their own work. Nelson Algren joined the Chicago office in a city reeling from the Depression. In later years, Algren would “credit the FWP for keeping the suicide rate down”; he went to work on an array of bread-and-butter assignments. But he was mostly a field worker, set loose to gather primary material. He “hung out around grimy boxing rings and gangsterish social clubs and the city night court; he observed inveterate gamblers and exhausted dance marathoners and denizens of the racetrack.” He wrote it all down, and this rich material helped form the core of Algren’s later novels, including “The Man with the Golden Arm” in 1950, which won a National Book Award.

The pioneering Black writer Zora Neale Hurston worked out of the project’s Florida unit, in a rigidly segregated state hostile to President Roosevelt’s New Deal. Hurston had made a name for herself as an anthropologist, folklorist, dramatist and author, and she resisted joining the FWP because of a required “pauper’s oath” certifying that applicants were indigent. But she needed the money. Easily the best-known author in the Florida office, Hurston was given the lowly title of “junior interviewer” and assigned to one of the project’s “Negro Units.” But Hurston had a talent for turning racial roadblocks to her advantage. As she worked on a new novel she would disappear for weeks at a time; her superiors would fire off a letter seeking an update and eventually a thick manila envelope would arrive, “stuffed with material on Florida folkways.” Much of it was material gathered for other projects, but it was gold no one else could have mined.

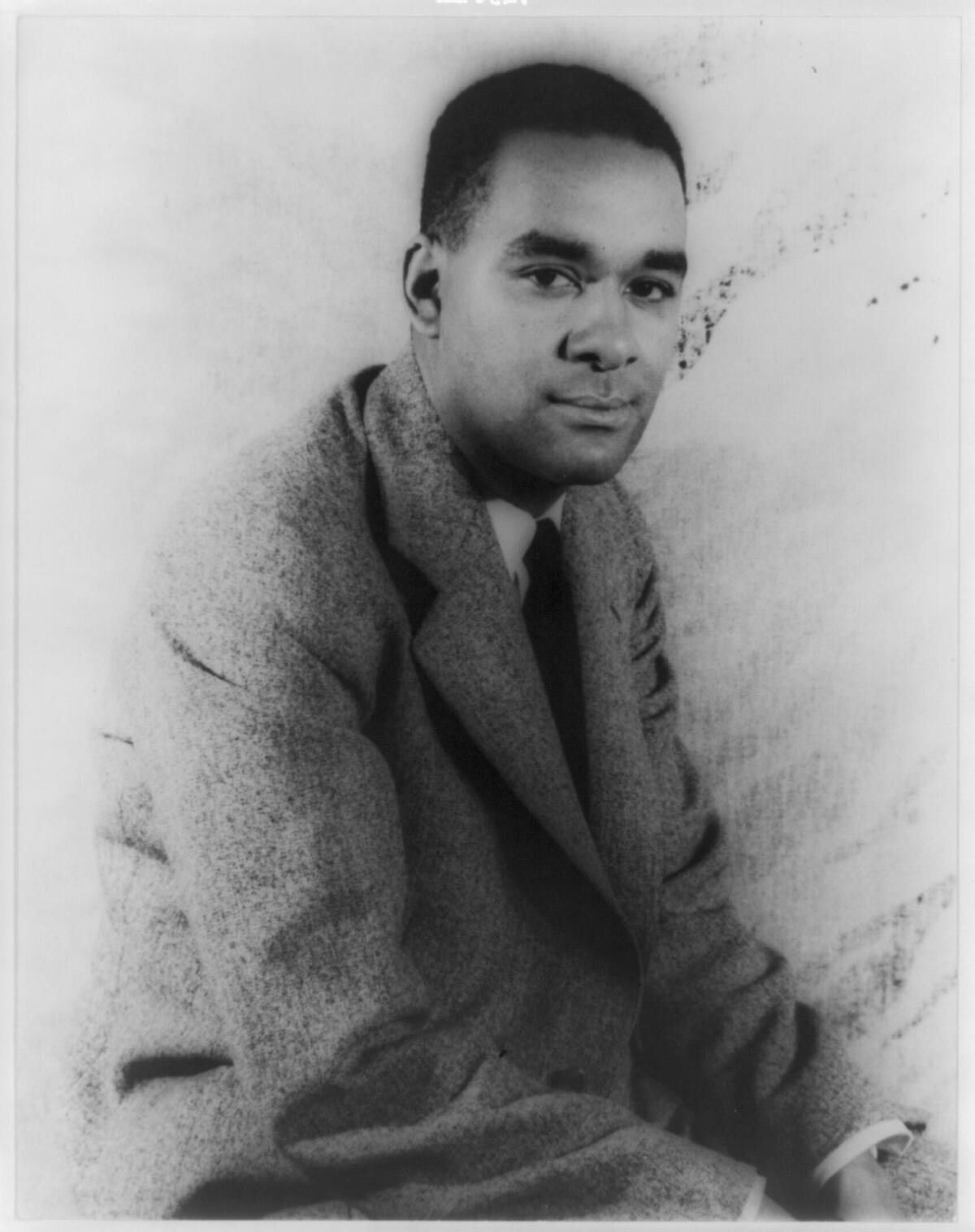

‘The Man Who Lived Underground,’ newly expanded from a story into a novel by the Library of America, may revise the seminal Black author’s reputation.

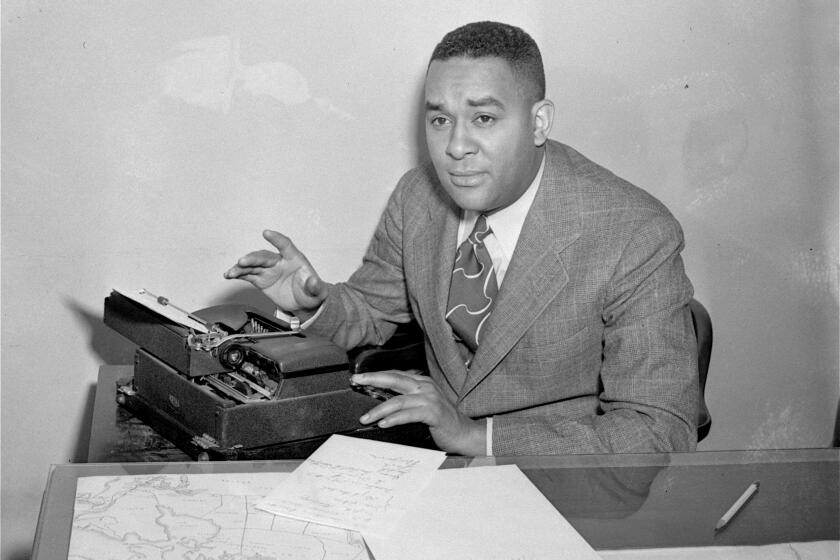

Hurston was a “keen strategist of racial deference,” and her views on America’s racial travail clashed with those of another project writer and seminal Black author, Richard Wright. But like Hurston, Wright turned work at the FWP to his advantage. Eventually, he got a grant to work on his own writing and produced one of the most searing indictments of American racism written, “The Ethics of Living Jim Crow,” his chronicle of growing up terrorized in segregationist Mississippi. Wright’s essay, collected in an FWP publication, fueled the animus of politicians aiming to kill the program.

As a management challenge, the FWP’s Manhattan office was the worst of the worst, a pot stirred by 31 different unions and splinters of unions including an active cell of the American Communist Party. One director, Orrick Johns, was beaten senseless by a spurned job seeker, who then “poured liquor all over John’s wooden leg and set it on fire.” When Rep. Martin Dies Jr. of Texas held hearings to investigate alleged Communist infiltration of the Works Progress Administration (the FWP was a division of the WPA), his committee homed in on the labor unrest as well as Wright’s essay, which one witness railed against as “so vile that it is unfit for youth to read.”

The Dies report put the FWP on life support. But by any commercial or literary measure, it was a raging success: By 1941 there were 268,967 American Guides in print, with nearly as many city and town guides. The FWP circulated more than 3.5 million items, and its liberal hiring philosophy kept thousands of people off the bread lines and engaged in meaningful work.

Today, with systemic unemployment worsened by the pandemic and many arts organizations decimated, Lieu’s legislation would seek to replicate this success in a 21st century version of the project. California legislators are considering a similar bill. Borchert has produced an essential road map for their efforts: “Republic of Detours” is a lively history of the project and its writers, but it offers something even more valuable: a lesson in the organizational challenges and poisonous politics that eventually doomed the FWP not in spite of its best intentions, but because of them.

On the anniversary of the birth of the Works Progress Administration, it’s worth asking what a post-COVID Federal Writers Project might look like.

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.