How Charles Yu fights anti-Asian hate and Hollywood stereotypes in his award-winning novel

As Charles Yu wrote “Interior Chinatown,” he worried readers wouldn’t be interested in a satirical novel about how Hollywood and society trap Asian Americans in stereotypical roles.

They almost never get to be the leading man. Instead, they get to be “Generic Asian Man Number Three / Delivery Guy.”

“I wondered if I would run into people who would say, ‘What is the big deal? Is it really such a big problem?’” recalls Yu, who joins the Los Angeles Times Book Club on May 27. “I thought I’d get skepticism. Does this story really need to be told?”

The author’s self-doubt turned out to be off the mark. “Interior Chinatown” received rave reviews and won the 2020 National Book Award for Fiction in November. After the pandemic triggered increased anti-Asian harassment and violence, Yu’s witty but pointed indictment of prejudice has resonated with readers in a way he never envisioned.

“I feel like both within the AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] communities and in a more general sense, people seem to be coming to it because of the events,” said Yu, a Los Angeles native who is the son of Taiwanese immigrant parents. “I think they want to read something about a character who’s talking about these issues, for stories that have this kind of perspective.”

For Yu, a corporate attorney turned novelist and television writer, figuring out how to channel his perceptions of cultural bias into a book was a struggle. He started trying to write “Interior Chinatown” in 2012, but kept finding reasons to put it aside. “I had a bunch of false starts and dead ends,” he recalls.

“When I started, I had a very different conception of what the book would be,” Yu says. “I had a lot of ideas about it having something to do with magic, with magical realism. I didn’t know what I was doing.” He tried different ways of telling the story, from a conventional novel to “another stage where it was fairy tales.” But none of those permutations felt right.

“I went through a lot of versions of it,” Yu recalls. “Maybe one of them would have worked. Maybe not. I was showing them to my agent, and she was really encouraging and supportive and enthusiastic about some of the material. Still, I felt from the inside that there was something that wasn’t quite getting unlocked.”

Yu credits his wife, Michelle Jue, for urging him not to give up. “Whenever there was a hint of me losing faith in the project or in myself as a writer, she’d remind me, ‘This is what you love most, writing fiction. This is what you are.’”

Five years into the project, in 2017, Yu had an epiphany. He was walking his dog near his family’s Irvine home when he suddenly heard the novel’s opening lines in his head: “Ever since you were a boy, you’ve dreamt of being Kung Fu Guy. You are not Kung Fu Guy.”

He recalls thinking, “Now I can hear the voice of the character.”

Steph Cha shares a meal and some notes on performing identity with the “Interior Chinatown” author.

That character was Willis Wu, the novel’s protagonist. Along with his parents, Wu lives in Chinatown and is cast as a background character in “Black and White,” a fictional police procedural TV series that’s a thinly veiled parody of “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.”

“I’ve watched a lot of ‘SVU,’” Yu says. “I’m a fan of the show. It’s just so binge-able; when it’s on, you could just keep going, watching it. But I think the police procedural format is so compelling for me to use, because it’s one of our dominant forms, like the superhero movie and the medical show.”

In addition to mimicking the format of a teleplay, Yu made another unconventional stylistic choice by writing in the second person. That allowed him to create a narrative from Willis’ perspective and simultaneously depict him as a character in a story told by someone else. “It gives me some flexibility,” Yu says. “There is a kind of squishiness to it.”

Once Yu figured out the form for “Interior Chinatown,” he says, the hardest part to write was the back story of Wu’s parents. “Some of that is based on my own parents’ experience,” he says. “It’s been fictionalized substantially, of course. But there is a basis in fact for some of those stories. I had a connection to that.”

Conceptually, it also was a challenge to figure out the rules by which the reality in the book operated. “I was asked pretty explicitly by my editor and my agent,” he says. “I really had to try to figure out what I was doing, and at times I got confused. It ended up being that the answer is complicated. Willis and the other Asians are performers, and they’re not. This Chinatown is real, and it’s not. I’m not settling for some easy answer.”

Yu says his willingness to experiment and take creative risks is partly a function of his unschooled, DIY background as a writer. A lawyer by training, he started writing in his spare time and endured scores of rejections before breaking through in 2006 with a collection of short stories, “Third Class Superhero.”

“I don’t have the tools you would get, getting honed by an MFA program, going through that rigorous workshopping with peers and teachers,” he says. “And I probably don’t have some of the confidence that comes from having that level of craft and awareness of it.

Former President Barack Obama and filmmaker Ava DuVernay discuss “A Promised Land” at the L.A. Times Community Book Club.

“But the flip side for me, at least, is that I don’t even know what I don’t know,” he continues. “I’m embarrassed by that, probably not having read a lot of things that other people have read. But I’m not bound by many rules because I don’t know many of them. It can be dangerous and scary, and it also has its own limitations. Every time I write something, I have to figure out what I’m doing.”

Yu also has an unorthodox writing process. When he’s writing a novel, he doesn’t bother with an outline. “I usually start with an idea or a sentence,” he says. Initially he’ll work on a laptop, but he switches to paper when he feels stuck, scribbling in journals at home or in coffee shops.

“Seeing my ideas all kind of randomly scribbled instead of typed in a uniform font down the page, that disrupts or frees up some kind of pattern,” he says.

“I’ve learned to be more comfortable just being in the mess,” he says. “I have no idea of where I’m going with this. That’s how I work.”

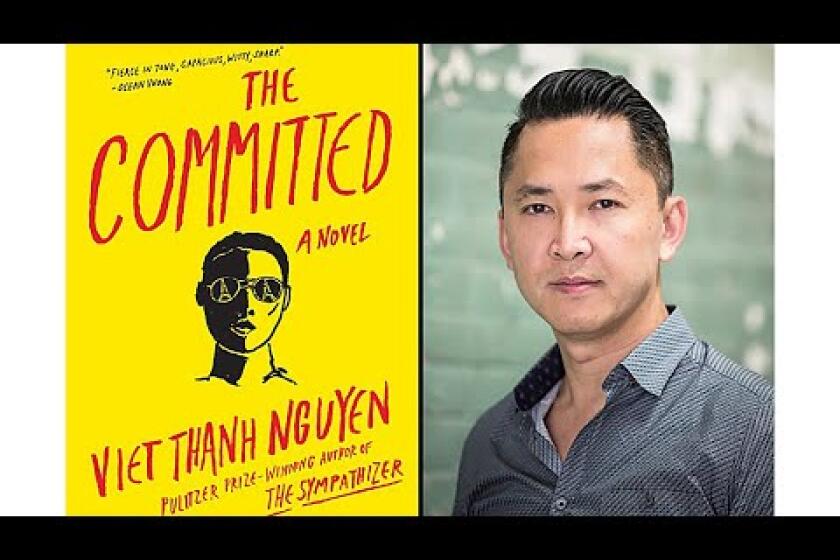

Watch author Viet Thanh Nguyen talk about “The Committed” at the L.A. Times Book Club.

Though Yu’s novel deftly skewers ethnic stereotypes and lack of depth in the depiction of Asian American characters in television dramas, he says he’s encouraged by some of what he sees onscreen these days.

“There are limitations to a medium, and there’s a limit to how fast progress really happens,” he says. Nevertheless, “TV is completely different from what it was 10 years ago, and even more so than it was 30 years ago. I see hope. Not to be complacent, but there’s more room for different types of stories and storytellers.”

Yu may get a chance to speed that evolution a bit. He’s writing a pilot episode for an adaptation of “Interior Chinatown” for Hulu. He acknowledges that it’s an odd twist to be writing a TV version of a novel that parodies a teleplay.

“It’s hard to wrap my head around the layers of meta,” Yu says, laughing. He expresses admiration for the intricate cleverness of “Adaptation,” the 2002 film written by Charlie Kaufman, about a fictional version of Kaufman struggling to adapt Susan Orlean’s book “The Orchid Thief.”

“I have to be willing to think really in a different way about this,” Yu says, “to figure out something that’s fresh and new.”

Book Club: Join us

Novelist Charles Yu, the author of “Interior Chinatown,” will be in conversation with Times film critic Justin Chang at the Los Angeles Times Book Club.

When: May 27 at 7 p.m. Pacific

Where: Free live streaming event on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. Sign up on Eventbrite.

More info: latimes.com/bookclub

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.