Appreciation: What writers learned from Barry Lopez while moon-gazing at a Dairy Queen

Appreciation

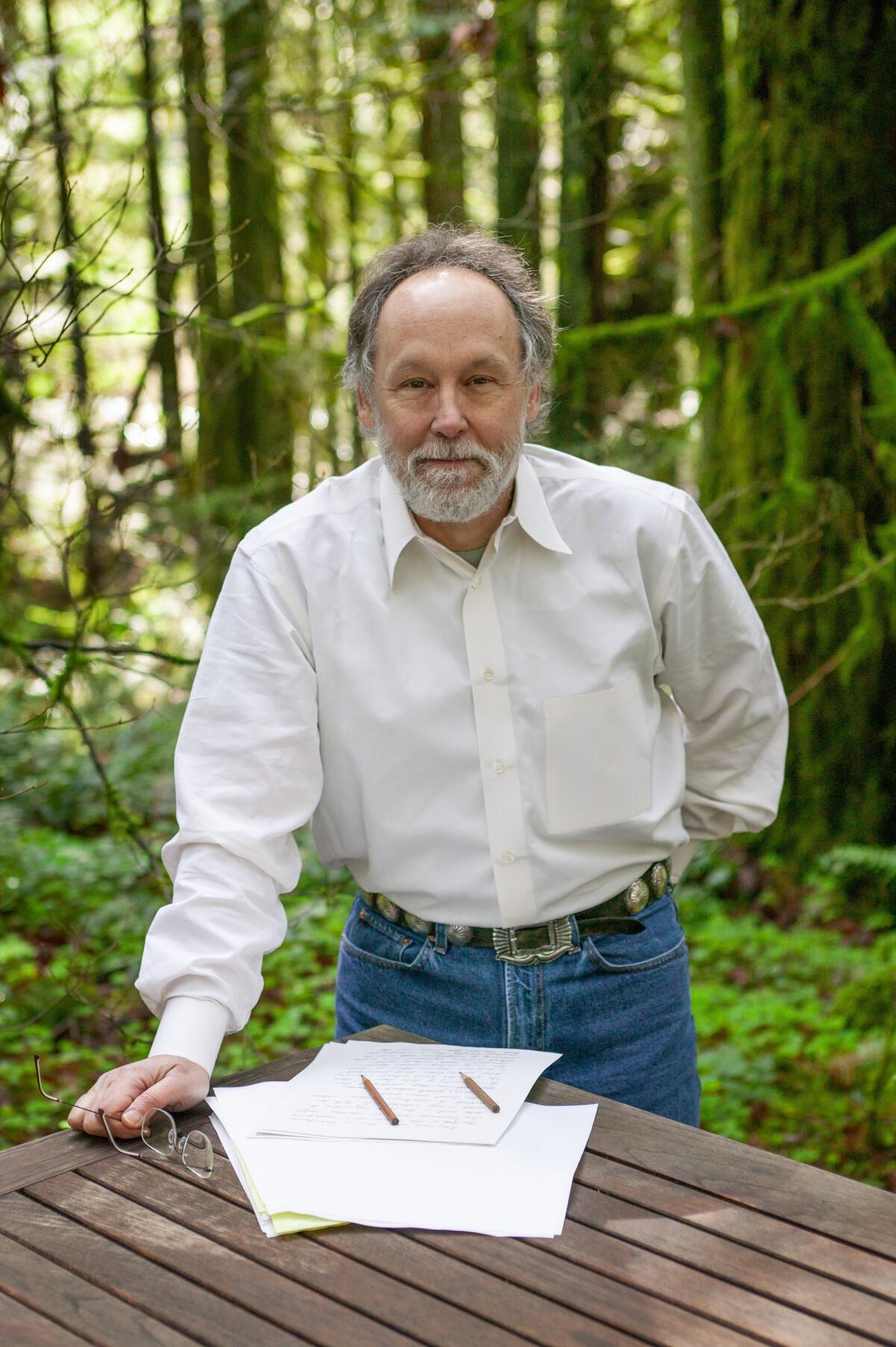

Barry Lopez

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“We are pattern makers,” Barry Lopez said, “and if our patterns are beautiful and full of grace, they will be able to bring a person for whom the world has become broken and disorganized up off his knees and back to life.”

Or that is what I heard, anyway, one July afternoon, in the room with the periodic tables on the wall at Pacific University, during a 10-day summer residency where I and others, including Barry’s wife, Debra Gwartney, and sometimes even Barry himself, taught young writers about their craft. I tucked his words into my pocket that day and took them with me. I quote them — probably inexactly — each time I stress the importance of form and structure to the writers I work with, as I strive to convince them that language is much more than simply the flatbed truck on which you deliver your story’s meaning, that form and language in combination make the meaning, just as the forms in nature make the Earth.

Over the course of our lives, Barry and I shared only a handful of dinners and conversations, a handful of classrooms and car rides, but two things allowed us to know each other deeply and well, even though we never spoke of them directly. Like Barry, I was serially sexually abused as a child, and also like him, I understood, even at that tender age, that in as much as I could be healed from those brutalities, it was the natural world that would allow for that healing. A couple of decades and a continent apart, Barry and I were both given the understanding that if we spent enough time learning the Earth and — this is very important — letting her learn us in return, she would give us back the thing that had been taken from us (and these are Barry’s words): the ability to articulate our meaning in the world.

Barry Lopez, an award-winning writer who tried to tighten the bonds between people and place by describing the landscapes he saw in 50 years of travel, has died

Since Barry’s death on Christmas Day, I have been thinking most of all about the example he set for those of us who try to write about our relationship with the Earth. He traveled to the Arctic, the Galapagos, Kenya, the Grand Canyon, Antarctica, Namibia, Australia’s Nullarbor Plain, not to see them but to learn them. He knew so much, but I think what I admired most about him is that he also knew what he didn’t know. He often said that to allow for mystery in your life, to admit what you don’t know, is to allow yourself an extraordinary freedom. One goal of his traveling, of his writing, was to allow that mystery to deepen.

He knew how to listen, how to enter a room and be quiet and wait. He spent his entire life listening — to the land, of course, and also and especially to the people indigenous to the land, people who had been caring for the land sustainably for 5,000 or 10,000 or 20,000 years. He recognized and respected their deep, land-based history, knew they were better attuned to nuance in their surrounding landscapes, admired the way they lived “in a kind of ethical unity with a place” where “their bonds to the earth are as much moral as biological.” He called their way of living “a fundamental human defense against loneliness.”

For decades, Barry had been in despair about climate collapse and the fate of the planet. He had also been deeply curious about the conversations we might have with one another in the face of a catastrophe unlike any humanity has known. He had been, in fact, rather insistent that we have those conversations. His most recent book, “Horizon,” a glorious and devastating culmination of his life’s work and learning, walks us, gently and tenaciously, into the reality that we will not likely arrest nor survive the coming climate collapse, and therefore how we treat one another and the planet in the interim, how we tell the Earth’s story, is far more (not less) important than we ever imagined. “All that is holding us together,” he said, “is stories and compassion.”

Jan Morris, the writer and transgender pioneer who died Friday, should also be remembered for her perceptive 1976 essay “Los Angeles: The Know-How City.”

On the evening of the day Barry said the thing about us being pattern makers, after the workshops and dinners and readings, I gathered up some of the faculty for a late-night run in my red rented Mustang convertible (an accident of assignment) to the Dairy Queen that perched out on the highway some 10 or 12 miles away. Of those gathered, I remember Barry in particular being excited about the possibility of a Peanut Buster Parfait. Most everyone else was just excited to get, for a minute, off campus. It was high summer in the Tualatin Valley of Oregon, the crickets were singing in the irrigated fields, and when we popped out of the rows of campus Sequoias and Douglas firs, we saw that the moon had risen, fat and full, over the wine grapes and strawberries and mustard. Debra said, “Look at the moon, Barry,” which begged the question: Could the rest of us in the car even see the moon as he did? But, of course, he had already seen it, was already studying it, as he did everything, as he did each of us.

In “Arctic Dreams” Barry wrote: “For some people, who they imagine they are does not end where the boundary of the skin meets the world. It continues with the reach of their senses out into the land. If the land in which they live is summarily disfigured or reorganized by industrial development, it causes them psychological pain.” He was writing about the Inuit people he met in the Arctic, and I also believe he was describing himself, and me, and anyone else who, by necessity, let the Earth mother them into adulthood.

In truth, none of us could see the moon like Barry saw it that night, because none of us had practiced seeing as long or as hard as he had. But a rowdy bunch of writers set briefly free from an MFA residency knew enough then to be quiet, to study the moon and wait for her to tell us her story. Barry was right there beside us, after all, showing us how.

Books about nature to read while avoiding the coronavirus — from classics by John McPhee and Annie Dillard to the upcoming “Book of Eels.”

Houston is the author of “Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.