A college admissions novel that’s less about gossip than complicity

On the Shelf

Admission

By Julie Buxbaum

Delacorte: 352 pages, $19

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When news of the college admissions scandal broke in March 2019, much of the nation was thrilled by its promise of good gossip and ample schadenfreude. The story had everything we love to hate-read — it was a tale of extreme wealth and extreme greed. Celebrities like Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin had collaborated with Rick Singer, a “private admissions counselor,” to fake test scores and athletic resumes in order buy their kids’ way into elite colleges. In a deeply divided nation, here, at last, was something we could all agree on: These people were monsters, and they deserved to be exposed, mocked and punished for their sins.

“When the scandal broke, I, like the rest of the United States, was totally and completely obsessed,” says Julie Buxbaum, “but times a thousand — more than anyone else.” Buxbaum is the author of five novels, mostly for young adults, including the New York Times bestselling “Tell Me Three Things,” but before she started writing, she was a lawyer. So she knew what she was looking at when she sat down and read through the actual case that had been brought by the Massachusetts district attorney — all 500 pages of it. Even that wasn’t enough; as Buxbaum explained during a phone call, the scandal “wouldn’t let me go.”

For all the information she’d gleaned from the legalese, Buxbaum was still left with questions that reached beyond guilt or innocence. Which is what led her to write her sixth book, out next week. “Admission” is a young adult novel about a teenage girl named Chloe who has just discovered that her parents faked her way into her dream school — and now her mother, a B-list actress best known as a charming sitcom mom, may end up going to jail for it.

Though the details are ripped from the headlines, Buxbaum lets us know in the novel’s introduction that Chloe isn’t meant to be a cipher for any of its familiar faces: “I do not know anyone involved in the scandal, nor did I do any investigative reporting.”

Christina Hammonds Reed was only 8 when L.A. erupted and slowly awakened to Black disadvantage. So does the narrator of her debut YA novel.

She wrote the disclaimer, she explains, because “it was important to me that I was telling a larger story, not the particular story of the famous names.” She wanted to ask broader questions about privilege, complicity and what we allow ourselves to know about the unattractive underbellies of our lives.

While no one ever tells Chloe explicitly what’s being done for her, she spends much of the time half-noticing how oddly her parents are acting: the sudden arrival of a private college counselor, something her prep school expressly discourages; her parents’ insistence that she has a heretofore undiagnosed learning disability; her father asking for a picture of her where she looks “tan.”

“I’m always interested in that gray area in life where you know something but don’t know something,” Buxbaum says, “where your instinct is at odds with what you want the world to be, so you sort of squash down the information. The central mystery of this novel is not whether her mom did it — we know as much immediately. The question is, how much does Chloe know, and when does she know it? Which is a much more interesting and morally ambiguous question.”

Buxbaum also wanted to explore the effect of that kind of parenting. “We had seen so much talk about the parents and why they did it, but not enough talk about the kids at the center of it,” she says. “What are you telling your child when you parent this way? What lessons are you imparting? You’re imparting a lesson of pure entitlement, like, ‘You deserve this no matter how hard you’ve worked.’ And second, you’re imparting a message of inadequacy — ‘You can’t do this on your own.’ Which are two conflicting messages. How do you navigate that as a teenager?”

It was important to Buxbaum that “Admission” doesn’t read as a plea for sympathy; instead, she sees it as an attempt to understand Chloe’s experience in all its messy complexity. “The point of the novel is not to make you like the main character but to understand them,” she says. “As a culture, we don’t have the impulse to understand these teenagers, but it’s important that we do, because it tells us this larger story about how we’re raising a generation.”

Federal prosecutors accused top CEOs, two Hollywood actresses and others of taking part in an audacious scheme to get their children into elite universities through fraud, bribes and lies.

Buxbaum lives in the Hancock Park neighborhood of L.A., and her kids, ages 8 and 10, are enrolled in the local public elementary school. But she’s familiar with the hypercompetitive world of private schooling and the way that the desire to give one’s child the best of everything can lead to tunnel vision that prizes personal gain over communal care. “There’s a literal limit to the number of spots” for these schools, Buxbaum points out. “We talk about how it takes a village to raise kids, but we’re pitting the kids against each other, so parents are not in it for the village.”

Ultimately, the questions Buxbaum asks apply not only to the extreme cases we see in the tabloids but to any parent who must draw the line between helping their child succeed and showing them how to live. We can all agree that what Singer’s clients did was appalling, but what about sending a child to an elite private school instead of a public one? What about getting them an SAT tutor, or having your professional writer mother give your college essay “a little polish”? One of the people Buxbaum was seeking answers for was herself.

Writing the book made Buxbaum reassess her own parenting, she says — it forced her to think through “all the sort of littler messages we send along the way, and how to tell them the right story of their privileges. I haven’t figured it out!”

In the meantime, Buxbaum is at work on a new book, set at the school Chloe attends, a prep school called Wood Valley that was also the setting for “Tell Me Three Things.” The three books are very different, she says, but their common thread is her interest in characters with privilege.

“It’s the moral boundaries,” Buxbaum says. “It’s the kids at the center of power. I’m ultimately fascinated by: How complicit are we? Every decision I make on behalf of my kid, which happens every day — how complicit am I in this system?”

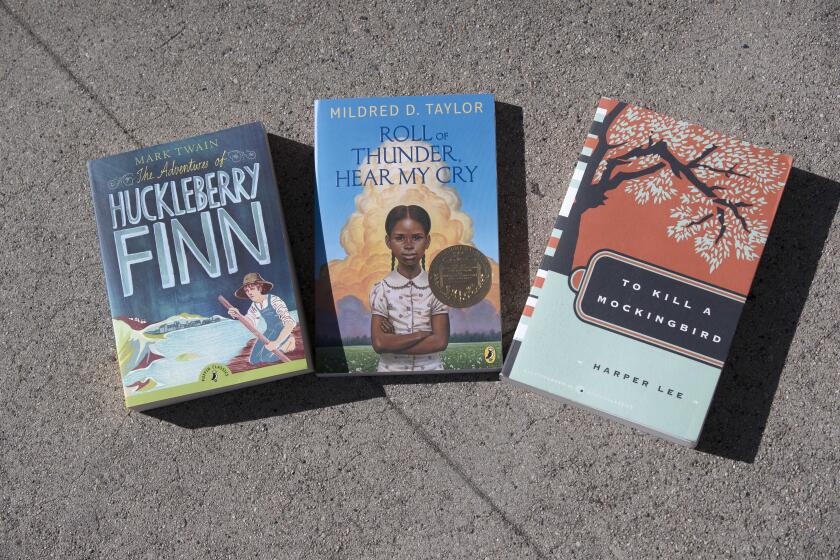

Some argue the books under review — including “To Kill a Mockingbird” and two YA classics — instigated racist incidents; defenders believe they’re antiracist.

Romanoff is the author of several novels for young adults.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.