Will China’s entry into U.S. publishing lead to censorship?

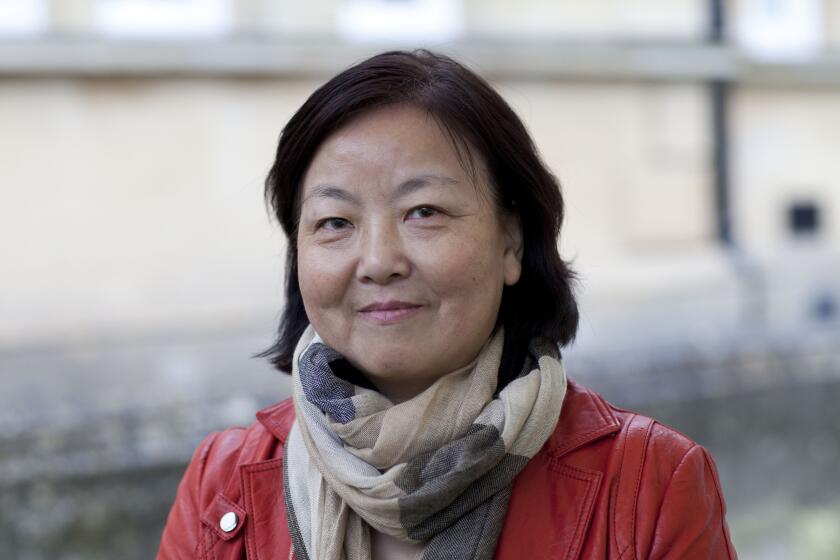

Roughly 100,000 Americans have died from what President Trump has disparagingly called “the Chinese Virus,” as reported by a media he labels “fake news.” Trump has accused China of deliberately obfuscating facts, possibly including the origin of the virus. Xenophobic fear-mongering aside, he might have found an unwitting ally in Fang Fang, a 65-year-old Chinese novelist who lives in the city of Wuhan.

Fang’s “Wuhan Diary,” which began as a series of blog posts, was published in English earlier this month in a translation by UCLA professor Michael Berry. Covering two months of lockdown, Fang reports details of privation and overcrowded hospitals that are embarrassing to the government, and she grows critical of its response, displaying a level of overt frustration not routinely expressed in China. The diaries, posted online each night, were read by tens of millions, making her a celebrity.

It remains to be seen if many in the United States will buy “Wuhan Diary.” It’s available only as an ebook, for $20, and could feel to exhausted Americans like old, distant news. In China, meanwhile, the government deleted Fang’s online posts almost as soon as she wrote them (but not quickly enough) and canceled her Chinese book publication. Fang and her translator have been subjected to online threats and harassment, accused of giving the West “a giant sword” with which to attack their country.

Of course, U.S. relations with China are hardly as black and white as either Trump or the champions of press freedom would make them out to be. We’re in business together, like it or not — and that’s true in publishing as well. Earlier this month came rare news in the slow and conglomerate-controlled industry: the announcement of a new New York house, Astra Publishing, which had already poached three A-list editors. Less of a focus in the press was the fact that Astra is the subsidiary of an ambitious, publicly listed book publishing giant based in Beijing.

Fang Fang, a novelist from Wuhan, has written an online diary every day under lockdown since Jan. 25. Millions of Chinese readers wait for her updates every night, hungry for an honest voice. Some of her entries are censored by the morning.

A tolerance for dissent

Until very recently, the literary relationship between the United States and China had been tenuous at best. There are relatively few titles translated from Chinese into English each year. According to Publishers Weekly’s translation database, just 25 books from China were published in English in 2019 and fewer than 20 are planned for this year. None have been big bestsellers or generated much public conversation.

One of the reasons there may be so little literary trade between the two countries is that a great deal of the most dynamic and honest writing in China is taking place online. (See a series of firsthand lockdown accounts on the site Paper Republic.) Turning online content into print books with global appeal involves a slow-motion alchemy managed by a variety of intermediaries, including agents, foreign-rights directors, translators and others. It doesn’t work well for urgent stories like Fang Fang’s.

Online writing communities are wildly popular in China — fueled not only by reports of newly minted literary millionaires but also by the relative freedom afforded to the writers. Conventional publishers in China are closely monitored by the state, which controls the process of issuing ISBNs (international standard book numbers), without which a book cannot be legally published.

Dissent has been tolerated so long as it remains outside the mainstream, but there’s always a line that cannot be crossed. Last year, the government forced several small platforms to shut down for months over publishing material deemed salacious. As a result, the largest self-publishing platform, China Literature, saw its valuation plummet from more than $1 billion to $250 million. It has since recovered somewhat, buoyed by management changes and pandemic-related reading, but the message has been absorbed: Self-censor, or else.

In 2018, Tencent — which owns China Literature — led a $51 million funding round for Wattpad, the Canadian social writing platform. Wattpad has been working closely with Hollywood, striking some 50 production deals; a story adapted from the site, “The Kissing Booth,” was one of Netflix’s most-streamed movies of 2018. Only weeks ago, Wattpad Studios announced that it had hired David Arata, the screenwriter of “Children of Men,” to adapt a young-adult mystery published on Wattpad.

Coming to America

Astra Publishing represents the most dramatic U.S. books investment by a Chinese company thus far. It was launched by Thinkingdom Media Group, a Beijing-based publisher with a stable of prestigious foreign authors, including Paulo Coelho, Alice Munro, Haruki Murakami and Zadie Smith. Thinkingdom first came to the attention of publishers outside China when it was reported to have paid an eye-popping $1 million for Chinese rights to Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.”

But that was in China. Here, Astra will be led by homegrown American talent: Publisher and COO Ben Schrank was recently president and publisher of Henry Holt; Alessandra Bastagli, lately executive editor at HarperCollins imprint Dey Street, will be editorial director; and Maria Russo, the New York Times’ departing children’s books editor (and a former editor at the L.A. Times), will run the children’s imprint.

Does Chinese investment portend more self-censorship? People working in the film business will tell you it certainly has. Chinese money has flooded Hollywood and brought some visible changes to certain movies — more Chinese heroes and settings, fewer dialogue-heavy scenes and, perhaps most importantly, less criticism of China. Writers and producers are sometimes made to sign agreements not to disparage the Chinese government, even privately. The NBA too has had to walk a fine line to secure business with China.

Astra’s first slate, expected to appear next year, includes one import that may or not be lost in translation — a memoir from Li Juan, “Winter Pasture,” about traveling into northwest China with nomadic Kazakh herders. Other titles are a little more surprising and seem to assuage any concern over immediate interference from Beijing. “Art in the Age of Cancel Culture,” by Farah Nayeri, will cover controversies in the art world, including protests over Dana Schulz’s “Open Casket.” “The Biuty Queens,” by Chilean writer Iván Monalisa Ojeda, is a collection of stories about New York City’s Latinx trans community.

Both books cover topics the authorities in Beijing might find uncomfortable. But according to Luís Miguel Palomares Balcells, whose literary agency made the deal for Marquez’s rights, the company isn’t in the business of propaganda: “We never had a single problem with Thinkingdom regarding censorship.”

Foreign ownership is hardly new to American publishing; in fact, it’s now the norm. Nearly all the largest U.S. groups are foreign-owned: Penguin Random House and Macmillan are German, Hachette Book Group is French, and HarperCollins is part of News Corp, which has Australian roots. Only Simon & Schuster is owned by a U.S. company, ViacomCBS, and it is up for sale. Nor is Thinkingdom the first Chinese-backed U.S. publishing house.

ViacomCBS puts Simon & Schuster up for sale. The publishing house is not a core asset, and the newly merged ViacomCBS is looking to shed properties.

Around 2014, Beijing-based Mediatime Books published under the CN Times Books imprint, and they were definitely not independent. Titles included “The Chinese Liberation Army” and “The China Dream: Great Power Thinking in the Post-American Era.” They have not published a new book in the U.S. since 2017.

“We want to grow our business wherever books are sold,” Schrank, Astra’s publisher, told me in an email. “So the U.S. is naturally a key ‘next market’ for us, because it’s a major market for everyone. … The need to share stories globally feels particularly vital now, given the current trend toward global populism.” Schrank emphasized that Thinkingdom is “an independent company,” implying that he will have the freedom to publish whatever he likes.

Independence can take on nuances of meaning in the context of China, where freedoms can be revoked overnight, pressure exerted in various ways. Fang Fang and her translator now know that well. Their U.S publisher, HarperCollins, which has offices in 17 countries but not China, is promising English-language readers “a fascinating eyewitness account of events as they unfold.” But to elements of the Chinese government and Fang’s online enemies, it’s just more “fake news.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.