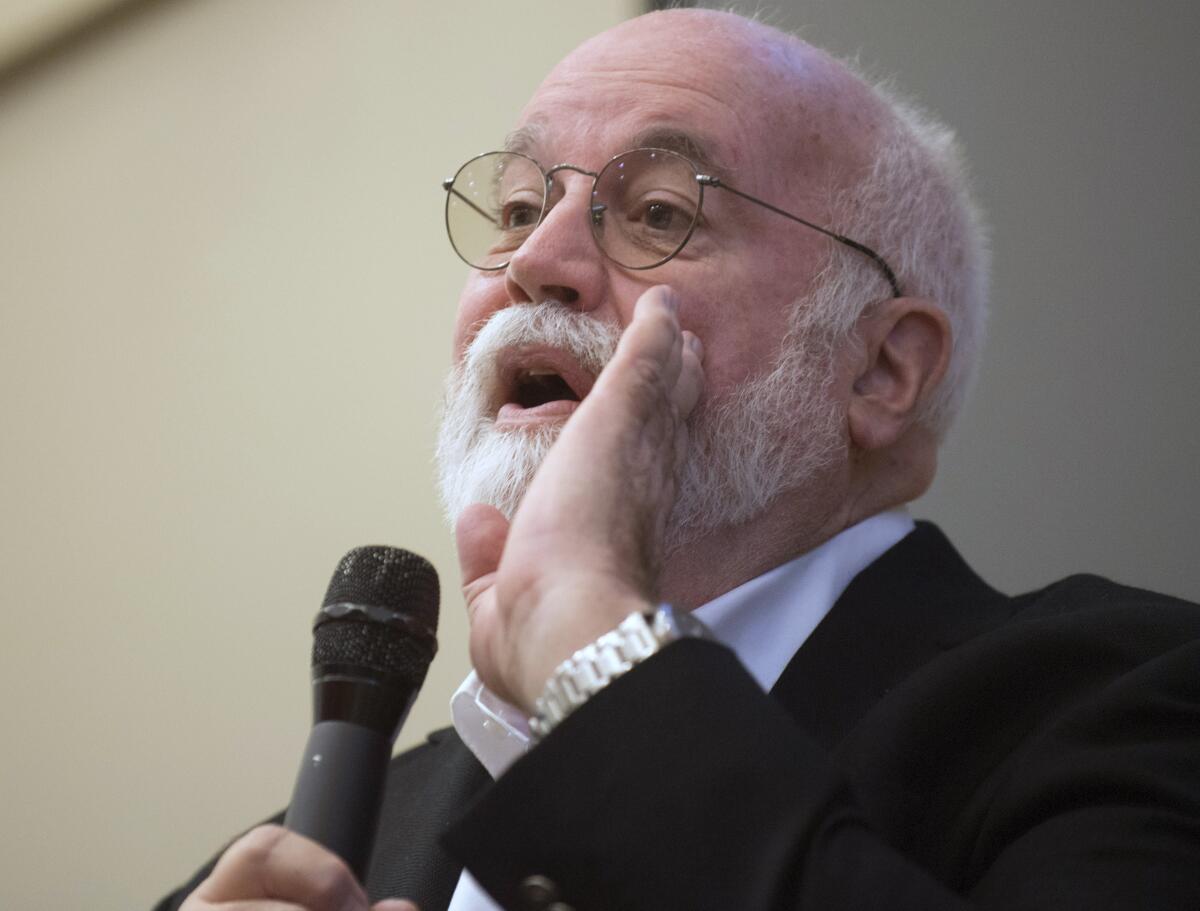

Father Gregory Boyle talks hope, homelessness and the power of kinship

Father Gregory Boyle says he believes in the power of a good diagnosis.

That outlook framed the Jesuit priest’s response to a question from a reader at Monday’s Los Angeles Times Book Club breakfast downtown. Her question:

“The two crises I see that just burden me are the homelessness crisis we have in L.A. and how immigrants are being treated right now. What hope can you offer us on those two things?”

“No treatment plan worth a damn was ever born of a bad diagnosis,” Boyle told an audience of about 300, who came to hear the Homeboy Industries founder talk about his latest book, “Barking to the Choir: The Power of Radical Kinship.”

“If you just think the solution to homelessness is a house, then I think it’s a bad diagnosis in the same way that jail is the solution to people who color outside the lines ... and then you discover everybody is born wanting the same thing, which touches upon the immigration issue.”

Boyle put it this way: “No kinship, no healthy immigration policy, because kinship is about saying, ‘We belong to each other: homeless, immigrant, gang member. There isn’t anybody who doesn’t belong.’”

Solutions to these pressing issues, he continued, “just won’t happen until you know that somebody sleeping under a bridge belongs to you, and a woman with her kids is fleeing this or that from Central America belongs to you, then nothing really gets changed. But that’s where we begin. And I believe that now I’m hopeful about making progress in that.”

The audience broke into applause.

In a conversation with author and journalist Héctor Tobar on Monday at the California Endowment, Boyle talked about his three decades providing jobs and counseling to L.A.’s gang members and how his work offers daily inspiration — and often humorous anecdotes — for writing two books. A third is in progress.

Boyle knows all about progress and new beginnings.

He started working with gang members in 1986 as a pastor in East L.A., founding Homeboy Bakery to provide job opportunities in his impoverished parish. That eventually became Homeboy Industries, which sees about 15,000 former inmates and gang members walk through its doors each year for services such as mental health counseling, substance-abuse support, tattoo removal, job training and perhaps soon, permanent housing nearby. This month Homeboy Industries was awarded a $1-million grant from the Everychild Foundation for a new youth reentry center, the organization announced on Twitter.

In “Barking to the Choir,” a follow-up to his 2010 bestselling “Tattoos on the Heart,” Boyle shares the lessons he’s learned about faith, kinship and compassion along the way.

During their conversation, Tobar noted the power of the personal stories Boyle shares in his writing.

“So much of what this book is is ordinary people who happen to be despised gang members, teaching us these lessons about life, that they’ve had to learn the hardest way possible,” Tobar said.

“Yeah, I kind of have this aerial view,” Boyle replied, talking about God’s “preferential care and love” for those who’ve suffered and have been “discarded, disparaged, demonized and left out.”

“Because they’ve suffered in that particular way, God thinks these are the folks who happen to be our trustworthy guides, to lead the rest of us to kinship and connection and community.

“That’s how I’ve always felt it, at Homeboy, that they’re my trustworthy guides,” he said, then clarified what he meant. “It’s not a romanticizing of something. It’s the real deal because I’ve never had to carry what they have to carry. ... I’ve never known the weight of complex trauma like they have. Which makes them the trustworthy guides. That’s why you go to the margins: not to make a difference. You go there so that these folks ... make you different.”

At the end of the book talk, audience members gave Boyle a standing ovation.

Later, some book club readers joined the staff at nearby Homeboy Industries for tours of the nonprofit’s headquarters, which includes Homegirl Cafe, classrooms, counseling spaces and a tattoo removal operation.

Tour leader Francisco “Franky” Reyes shared his story of watching his older brother get killed in front of him as a small child and then joining a gang years later to seek justice. Reyes landed in prison and in a wheelchair from a gunshot wound.

“My heart was in a really bad place — my outlet was a gang,” Reyes, 28, told the group. Now he’s working at Homeboy and preparing to study linguistics.

Thomas Reem Cotton, who attended the book club talk and follow-up tour, said he was moved by the massive impact Boyle has had on the lives of the people at Homeboy Industries.

“It was certainly eye-opening,” Cotton said. “It’s showing you the power of what can be done if folks are willing to treat everyone with a measure and level of respect and appreciation just for their existence.”

For updates about future book club events, sign up at latimes.com/bookclub.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.