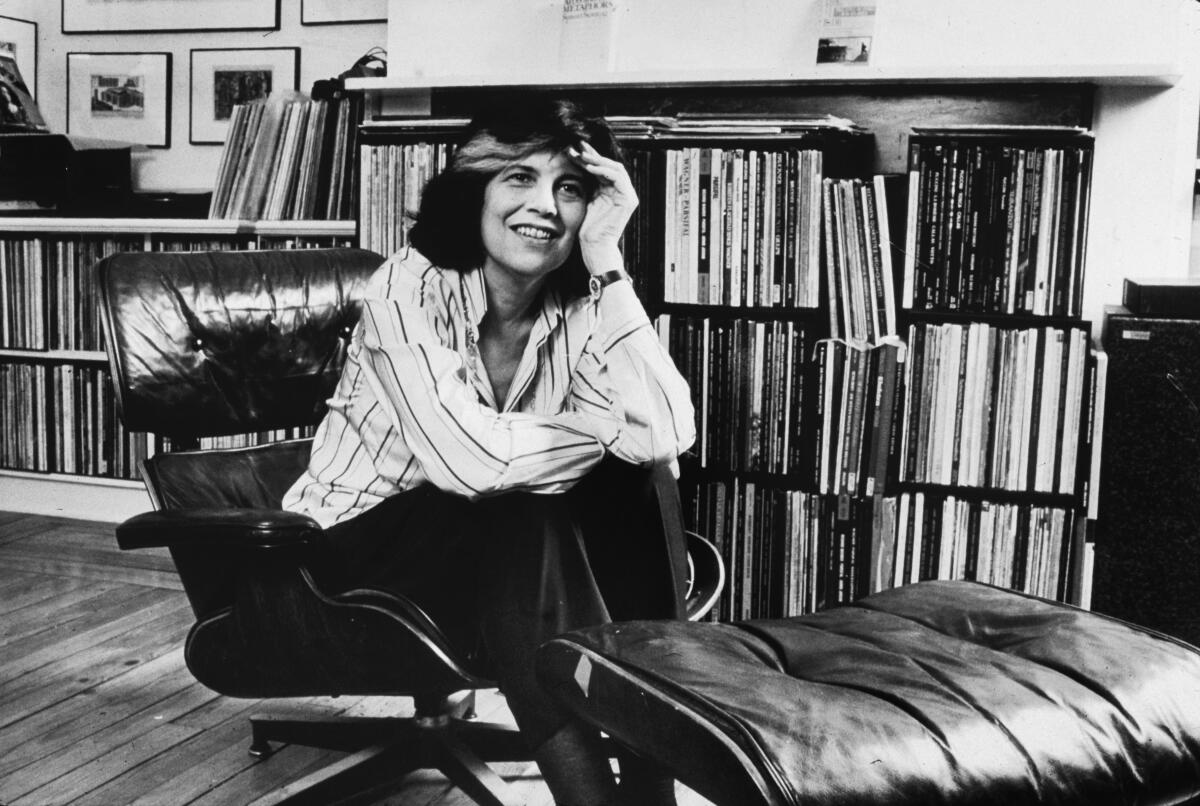

Review: Biographer pulls back the curtain on Susan Sontag’s life

The young woman who would become Susan Sontag, one of the 20th century’s most visible American public intellectuals, wrote constantly about her life in private, in diaries.

She rarely did so in public. In a rare memoir, “Pilgrimage,” she describes an afternoon in December 1947 when she and what seemed to be a high school boyfriend went to the home of the writer Thomas Mann and had a conversation with him about his books and ideas. They had looked up Mann in the phone book after learning that one of Germany’s greatest living writers at the time also lived in Los Angeles. They called him and to their surprise, he invited them over. They left filled with a mix of awe and disappointment familiar to anyone who finally meets a famous writer.

Benjamin Moser goes over this episode in his fascinating biography “Sontag: Her Life and Work” and pieces another story out of her manuscripts and diaries, as well as Mann’s diaries. Sontag was not in high school when she went, but in college. The afternoon was an evening and was in 1949. There were not two visitors but three, and none were linked romantically. A novel she describes as awaiting publication, “Faustus,” was already published by then, and she had shoplifted her copy from a store.

This all could as easily have been presented by Moser as a reason to shame Sontag, but in his hands it becomes a story about the shame and what she was trying to hide. She had just begun her first affair with a woman. She was forcing herself to be bisexual, was ambivalent about her Jewish identity, and would shortly marry her teacher at the University of Chicago, the sociologist Philip Rieff.

As Moser says, “The facts were fake. But the shame was real.” He sees in what she sought to hide the emotional truth of fiction — about her sexuality and also Mann’s. This complex sense of Sontag as a writer, made from who she was to herself and others, over time, strikes me as Moser’s real subject and the project of the larger book: The story even she wouldn’t tell herself. That is also a story about the century.

**

Sontag purchased her first diary “at the corner of Speedway and Country Club in Tucson.” Her first entry: “Someday I will show this to the person I will learn to love: — this is the way I was, this was my loneliness.”

That person would seem to be her only son, David Rieff, born to her when she was 19, and editor of the two volumes of her diaries. These are a part of a vast trove of papers Sontag sold before her 2004 death to UCLA and one of the most significant resources for Moser, along with 300-plus interviews with her friends, editors, enemies and lovers. The resulting details are stunning in number and quality, and range from the film her mother, Mildred Rosenblatt, appeared in as an extra to the designer label on the dress Sontag wore into her grave: Fortuny.

Moser’s Sontag is someone he works to understand as both a girl forever in love with her beautiful, alcoholic, widow mother and a woman who regularly castigated herself for not already being who she wanted to be, as if her ambition made a liar of her. She was regularly underslept as she hoped always to write a little more than she had, and as accomplished as she was, she died before she felt she had accomplished her final ambitions.

Her struggle to be bisexual is shown in relationship to her need to be more than she was — the lack that always drove her — a sign she was not, somehow, possessed of the self-acceptance she sought to portray. When, many years later, she urged a young Edmund White to “transcend” his gayness, in other words, it was a sign that she herself had not.

Moser’s first book, “Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector,” was a finalist for the National Book Award in nonfiction. It’s too soon to say he only writes about glamorous women writers at the center of their countries’ cultural lives, but thus far it is at least a coincidence. Lispector, like Sontag, lived inside a myth that fed her even as she fed it. Moser’s biography of Sontag is an education in Sontag, but also in what Sontag wanted and why, as well as an education in the worlds that inspired her and fought her.

Moser also finds in her a Zelig-like knack for being an eyewitness to some of the most significant events in 20th century history: postwar Los Angeles; the queer underground scene of San Francisco in the 1940s; the University of Chicago and Harvard in the 1950s; the start of the Cuban revolution; Vietnam during the war; Israel during the war; Sarajevo — also during the war; the fall of the Berlin Wall. She lived in New York City for two of the greatest tragedies in the life of that city: the AIDS crisis and 9/11.

As a result, her biography must also be something of an intellectual and political history of the 20th century United States. And it is animated by some of its most historically significant gossip. Her 1990 MacArthur Fellowship, for example, came with the news that she had been blackballed previously by Saul Bellow, who “loathed Sontag personally, and had a long record of opposing grants to women and ‘militant blacks.’”

An abbreviated history of 20th century literature is visible in just that item, much the way a history of 20th century American queer identity is visible in her 25-year relationship to photographer Annie Leibovitz, one of the more talked-about open secrets of New York in the 1980s.

The book’s cover copy calls it “a Great American novel in the form of a biography,” and if so, it is one Sontag never dared to write, ironically visible only in this story of her life.

Sontag: Her Life and Work

Benjamin Moser

Ecco: 793 pages, $39.99

Chee is most recently the author of “How to Write an Autobiographical Novel.” He is a Times critic at large and an associate professor of English and creative writing at Dartmouth College.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.