Review: Uber’s guerrilla tactics and tech-bro parties chronicled in ‘Super Pumped’

You’d expect a private security firm — say, the notorious Blackwater — to employ ex-CIA, Secret Service and FBI operatives to snoop on enemies and conduct espionage, tailing political figures, snapping their photos and communicating through an encrypted app that keeps messages from being traced.

But a San Francisco ride-sharing company?

Yet, indeed it was so, as Mike Isaac reveals in “Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber.” The New York Times technology reporter spins a compelling yarn that chronicles the transit company’s unruly development, from its two-entrepreneur start-up days in 2009 to its explosive expansion into a publicly traded, billion-dollar global behemoth, often aided by spying on competitors and outwitting transportation regulators.

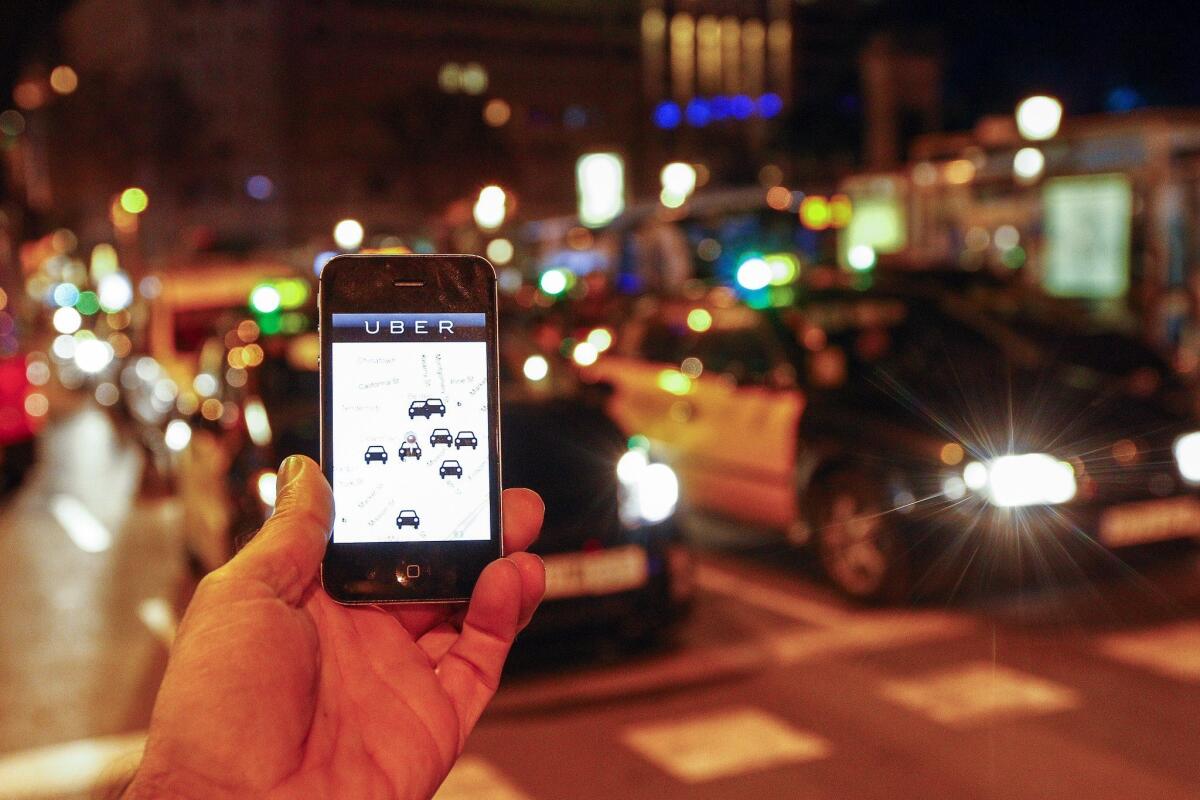

For those unfamiliar with Uber’s early days, the pioneering ride-hailing service took off when the invention of the iPhone delivered a seamless path to beating traffic and the entrenched taxi cab industry. An Uber app displays a street map that connects needy riders with passing drivers, all paid for by credit card so no one fumbles for change.

The book’s central character is founder Travis Kalanick, whose steady rise and ultimately humiliating downfall has long been in the news. But Isaac goes deeper into how this sometimes mesmerizing, always frenetic product of Northridge and UCLA developed his tireless drive to win, even if it meant burning through billions of dollars in expenses or surveilling the movements of competitors such as Lyft.

“One Lyft executive grew so paranoid about being followed by Uber,” Isaac writes, “that he walked out onto his porch, lifted both middle fingers in the air and waved them around, sending a message to the spies he was absolutely sure were watching.”

For every round of business success in Uber’s early days, Kalanick would keep his workforce “super pumped” by throwing lavish bacchanales in places like Miami and Las Vegas, the latter capped with a special appearance by Beyoncé. Misbehavior was common.

Kalanick was so eager to constantly expand that he let his managers run their own far-flung regions, regardless of how inexperienced they were at directing people or spending the hefty budgets Uber provided for advertising or discounts that might spur ridership. It was a “brilliant” move, Isaac writes, even if “giving too much autonomy to a legion of twentysomethings” let some managers go off the rails. The New York office was infamous for its aggressive “bro culture.” And one tacky promotion in France offered “free rides from incredibly hot chicks.”

Isaac also provides a cogent explanation of what it takes to succeed in the multibillion-dollar tech world of Silicon Valley. If you don’t know what the all-important venture capitalist really does, for instance, this book will tell you.

Much of any VC’s success depends on finding the right “founder,” someone who not only holds the vision but has the stamina to devote every waking hour to building out and scaling up while attracting new investors and inspiring employees to work just as hard. Kalanick was all that.

Kalanick viewed Uber as a crusader “battling the under-handed, street-fighting entrenched interests … who were colluding to keep taxi service bad and overpriced.” He would launch Uber into city after city without going through the usual regulatory channels, such as paying medallion fees required of cab drivers.

“‘There’s been so much corruption and so much cronyism in the taxi industry … that if you ask for permission upfront for something that is already legal, you’ll never get it,’ Kalanick once told a reporter.

Uber strike teams would descend on a region like paratroopers, at first contacting limousine and town car companies and persuading their drivers to fill idle hours by working with Uber. The “guerrilla tactics far outmatched the resources and technical acumen of government workers or taxi operators,” Isaac writes.

And inside state capitols and city halls, the company was ready to play hardball: At one point, Uber employed more lobbyists than Amazon, Microsoft and Walmart combined, Isaac reports.

It was the rise of Lyft that caused Uber to shift from hiring only limo and town car drivers, who were already licensed and insured livery vehicle operators. Lyft began letting anyone with a Class C license shuttle passengers using their own personal cars, meaning it had no fleet to lease, insure, keep fueled or service. So Uber did the same.

Lyft was a particular burr under Kalanick’s saddle. A la President Trump, he would use Twitter to needle and harass Lyft’s founders — “You’ve got a lot of catching up to do” — and he worked to impede their growth by dissuading venture capital firms from providing any money. Uber even bought a billboard in San Francisco, showing a giant razor blade about to take a swipe at a pink mustache, Lyft’s trademark.

But like a tenderfoot scout who confidently builds a campfire only to end up burning down the forest, Kalanick’s loose management — of his staff and himself — paved the way for a cascade of embarrassing scandals by 2014.

Apple executives were outraged when Uber engineers found a way to defeat an iPhone privacy update because it blocked them from tracking accounts created by fraudsters in China. There was a dust-up over whether Uber’s self-driving car division was using data swiped from Google. A resulting lawsuit was settled in 2018 when Uber gave Google $245 million worth of stock. (On Aug. 27, a federal grand jury indicted former Uber engineer Anthony Levandowski on 33 counts of stealing or trying to steal trade secrets he obtained when he worked at Google.)

And in 2015, an Uber manager was accused of propositioning Susan Fowler, a young site reliability engineer, on her first day on the job. When Fowler reported the harassment, human resource representatives said they would only reprimand the manager since he was a “high performer” who had no other complaints against him. She later found out that other women had also been targeted. After only a year, she left Uber — and then blogged about her experience.

Just as the #MeToo movement was gaining political steam in 2017, the blog details catapulted Fowler onto the cover of Time magazine’s Person of the Year issue, alongside actress Ashley Judd (Harvey Weinstein), Taylor Swift (a Denver radio DJ) and more than 30 other sexual harassment “silence breakers.”

Former Atty. Gen. Eric Holder was hired by the company to investigate that and other Uber missteps, and the report he delivered was a shocker. According to Isaac, Uber board member Bill Gurley, the venture capitalist closest to Kalanick, felt it “read like a lewd magazine, a racist, sexist Silicon Valley bachelor party.”

By then, the board of directors knew Kalanick had to go if Uber was to survive.

This is no dry business profile but a tale that Isaac has deeply reported yet still made accessible. The details about how Kalanick furiously scrambled to fight back would make a darn good Hollywood movie. But kids, don’t wait for that: Look up from your phones now and see where all those Uber fares have really been going. It won’t take long.

Nottingham, a former Times journalist, edited government and transportation news when Uber arrived in Los Angeles in 2013.

Super Pumped: The Battle for Uber

By Mike Isaac

Norton: 408 pages, $27.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.