How VFX updates take Godzilla back to its nuclear roots

“Godzilla: Minus One’s” Takashi Yamazaki is the first feature director to be nominated for a visual effects Academy Award since Stanley Kubrick in 1969. That was for the medium-changing “2001: A Space Odyssey,” something the 59-year-old Japanese filmmaker is abashedly aware of.

“Thank you so much for even mentioning it,” a blushing Yamazaki says through an interpreter on a Zoom interview from his single-floor Tokyo CG studio, where a 35-person crew made Japan’s 70-year-old king of kaiju monsters look better than ever. “I don’t think I can really process that right now. I definitely can’t get carried away!”

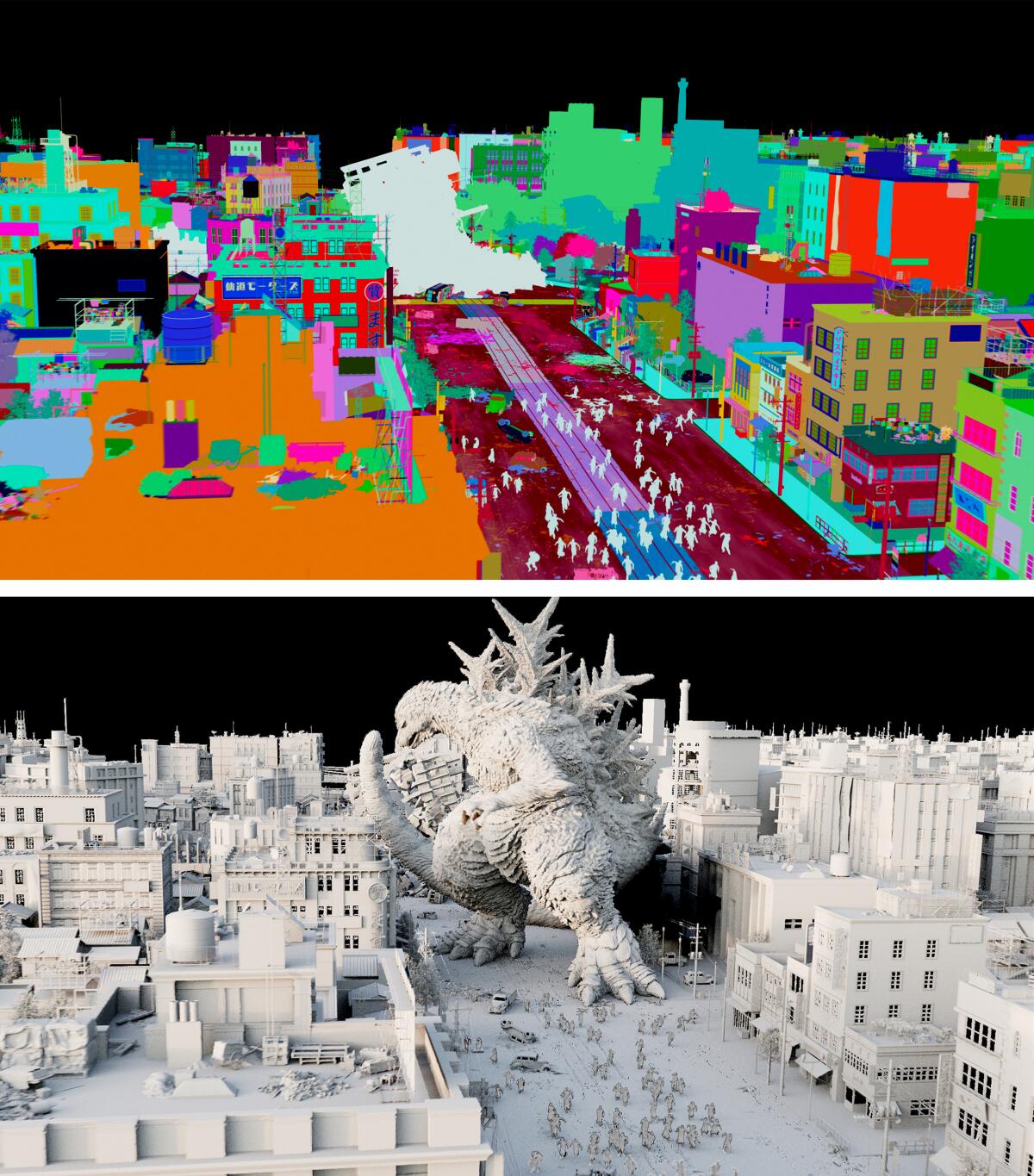

Yamazaki definitely has a knack for self-control. “Minus One’s” rich, gorgeous visual effects, seen in two-thirds of the unusually emotional, 38th Godzilla movie, cost between a quarter and a third of the film’s bargain-basement budget (less than $15 million). There were no limits to his formal ambitions, though. Set primarily two years after World War II in devastated Tokyo and the nearby Pacific, “Minus One” indulges lavish recreations of 1940s cityscapes in various stages of repair (which are again, of course, soon demolished), spectacles at and under the sea of the giant, radioactive lizard battling flotillas of warships, and the most persuasively beastial Godzilla ever filmed.

“We wanted to make Godzilla very, very cool for this film,” says Yamazaki, who after much trial and error utilized aesthetics his team employed for the “Godzilla: The Ride” attraction at Japan’s Seibuen Amusement Park. “The head is on the smaller side, the legs are very thick. When the feet are stomping on the ground, you can almost see the toes being raised, like a wild animal’s. And we wanted impact for the audience, so there’s an intense level of getting up close, personal and detailed, that you can’t really do with a man in a suit.”

Yamazaki refers to Toho Studios’ original method of filming Godzilla rampages in 1954. But his movie’s creaturific particulars surpass those of Legendary Entertainment’s nine-figure Monsterverse adaptations as well.

“In terms of polygon counts, we’re talking millions that went into creating Godzilla this time,” says Yamazaki, who did initial drawings and sculpture software models that were then refined by artist Kosuke Taguchi with optimized computer graphics data. “In terms of the skin texture, there was a dinosaur origin, but when it’s wounded, a regeneration happens and there’s a different texture, like you would see on any wound. We wanted a mix, brought in new layers that would make the look very unique.”

Also distinctive is how the monster’s super-spikey dorsal fins realign and emit blue radiation light as he fires up his devastating heat ray.

“We wanted to go back to the original reason for Godzilla’s existence,” Yamazaki explains. “The creature is a metaphor for nuclear weapons, so we mimicked the way a weapon would work inside of his body. Each element would come together and create an implosion, and that’s when the blue rays would come out.”

Since Godzilla grew out of Japan’s atomic bombing trauma, his destruction of Tokyo’s Ginza district and assorted ships culminate in terrible — but gorgeous — mushroom clouds. Trouble was, the look Yamazaki craved was too big to simulate in CG. An old-fashioned technique saved the day for the otherwise computer-generated spectacle.

“We had a matte artist who did 2-D that had a little bit of movement,” the director says. “Once we found that that switch was actually working, we were like, ‘Oh, my gosh, we spent so much time with CG that couldn’t get it, but now we have this really cool trick to get the mushroom clouds in there!’”

Japan’s Toho Studios, originators of the original ‘Godzilla,’ produce a satisfying update, modernized by new FX technologies but set in the post-WWII period.

Simulating water also takes up reams of CG space. But thanks to young compositing artist Tatsuji Nojima — who was elected by the whole VFX crew to share Japan’s first nomination in the category with supervisor Yamazaki, effects director Kiyoko Shibuya and CG team leader Masaki Takahashi, more seagoing shots became doable than initially planned.

“He was very much into water simulation,” Yamazaki says of Nojima. “He had built his own super computer at home and was like, ‘Can you please take a look at what I’ve built out here?’ We were so blown away that we added more water scenes into the scenario. In the end, I think we went a little overboard!

“Building water simulation is very data-heavy. You can’t easily create that and assume that everything is going to work. One simulation would take an average of a week; we’d build one, use it, then basically have to empty the drive of data to build the next one. The entirety of the water simulation tallied up to one petabyte, which is 1,000 terabytes.”

The trawlers and decommissioned Imperial Navy ships that confront Godzilla were all digitally built from the single practical vessel the production could afford to photograph. Yamazaki’s computer crew got so accustomed to labor-intensive work that, when it came time to rerelease the movie in black and white, still more VFX were added.

“I want to say it’s scarier because it feels like it’s happening in real life,” Yamazaki says of the monochrome edition. “It’s a different level of scariness than the color version. We didn’t just tint it and turn on a black and white switch; almost each cut, we added a touch of special effects to meet the standards of what this would look like if it were shot in black and white.”

None of this is unusual for the director, who’s been immersed in VFX his whole career. He started at Shirogumi VFX in 1986, and by the mid ‘90s was creating effects for films by the late Juzo Itami. Since 2000, Yamazaki has directed a wide range of features from anime to slice-of-life dramas to science fiction and historical epics, wearing the VFX supervisor hat at the same time.

His love of movie magic goes further back than that, though, which makes this nomination extra special.

“I had always looked at Hollywood as the ultimate goal, from the day I saw ‘Star Wars’ when I was really young,” Yamazaki says. “Unfortunately, I was born in Japan, so I always felt the technology in the West was advancing at such a fast speed that I didn’t know when I could catch up.” Now, that he has, he says, “to be in the company of so many talented people with the same background, it’s not only an honor, it is a dream come true.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.