When famous people get lost behind their look, Oscars tend to notice

With increasing, almost predictable regularity, Oscar voters have shown a preference for famous people going to great lengths to play other often-famous people in fiction or history. Scan the list of lead actor or actress nominees just in the 21st century, and a regular pattern reveals how spending hours in the makeup chair weighs the scale in favor of getting a nomination. It worked for Daniel Day-Lewis in “Lincoln”; when Rami Malek learned to sing with Freddie Mercury’s overbite in “Bohemian Rhapsody”; and when Nicole Kidman tacked on a new nose to play Virginia Woolf in “The Hours.” Intense transformations were a key part of heralded movies again this year. Here’s how some suffered for their art — and potential Oscar recognition.

“Golda”

When you are transforming one icon into another, it pays to be prepared for intense scrutiny. The opening shot in “Golda” focuses in extreme close-up on the eyes and eyebrows of Helen Mirren as Golda Meir, Israel’s first female prime minister.

The ‘Queen’ actor transforms into Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir in Guy Nattiv’s ambitious but under-realized drama about the Yom Kippur War of 1973.

The film’s hair, makeup and prosthetics designer Karen Hartley Thomas practically gasps when recounting the camera lingering on her makeup work. “So close! So massively close!” she said. “We had tested those eyebrows. It’s always a fine line getting these things right and not being a caricature.”

Mirren, 78, is virtually the same age as the 75-year-old Meir was during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the period covered by the film. Transforming the elegant British actor into the matronly prime minister required prosthetics for the cheeks, chin, nose and neck, plus contact lenses and a wig. The designer fashioned a replica wig after learning from Meir’s family that the leader wound her long, braided hair into a bun.

Hartley Thomas used her makeup magic to create wrinkles, shadows and the skin tone of an elderly person without obscuring the human underneath: “Actors are a little bit reluctant with heavy makeup because it can look mask-like.”

Though daily makeup applications could last 2½ hours, “we wanted to make it as easy on Helen as we could,” Hartley Thomas said. “You need it to look as natural as possible. That sounds strange with such a massive makeup as this, but we really went for the minimum.”

“Priscilla”

The trailer for director Sofia Coppola’s “Priscilla” opens with shots of Priscilla Presley applying eyeliner, false lashes and lots of hairspray, a snapshot of her transformation from child to her husband’s version of a sophisticated woman.

For writer-director-producer Sofia Coppola and star Cailee Spaeny, doing right by Priscilla Presley while demystifying her life with the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll was key.

Yet in this retelling of Presley’s memoir, “Elvis and Me,” her hair is almost like a silent character, which hair designer and department head Cliona Furey used to help tell her story.

An ambitious, out-of-sequence 30-day shoot meant Furey had to devise a scheme to rapidly transition actor Cailee Spaeny across 14 years, a process she said required “finding the balance of a little creative license and hitting the iconic moments properly and respecting historical accuracy.”

A period specialist, Furey used her personal collection of vintage wigs, accessories and hairpieces along with vintage techniques such as curlers with wet sets, teasing and inserts for height on the 20-plus cast members. Five frequently restyled wigs take Priscilla from a 14-year-old in a ponytail and bangs to a young bride, mother and style-setter with enormously high hair.

“I put her in a similar color for that last wig as the first wig to help the story arc,” Furey said. “It was me getting our hair backstory in there.”

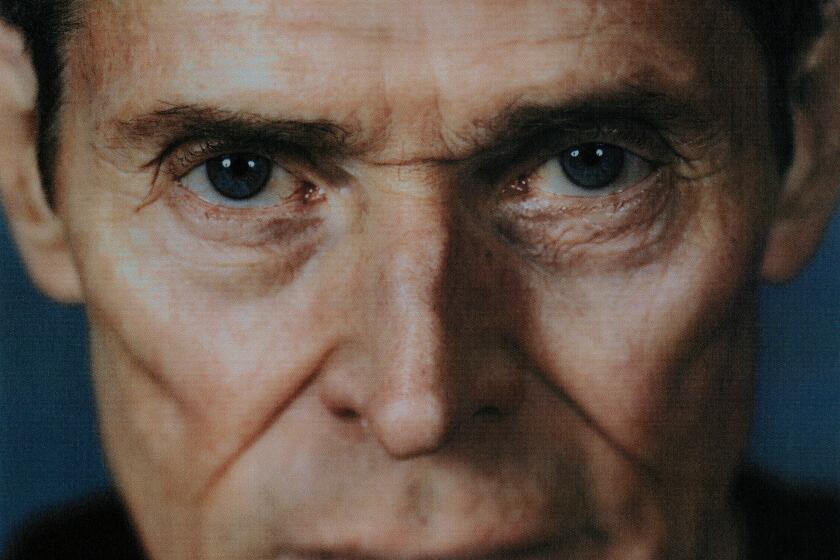

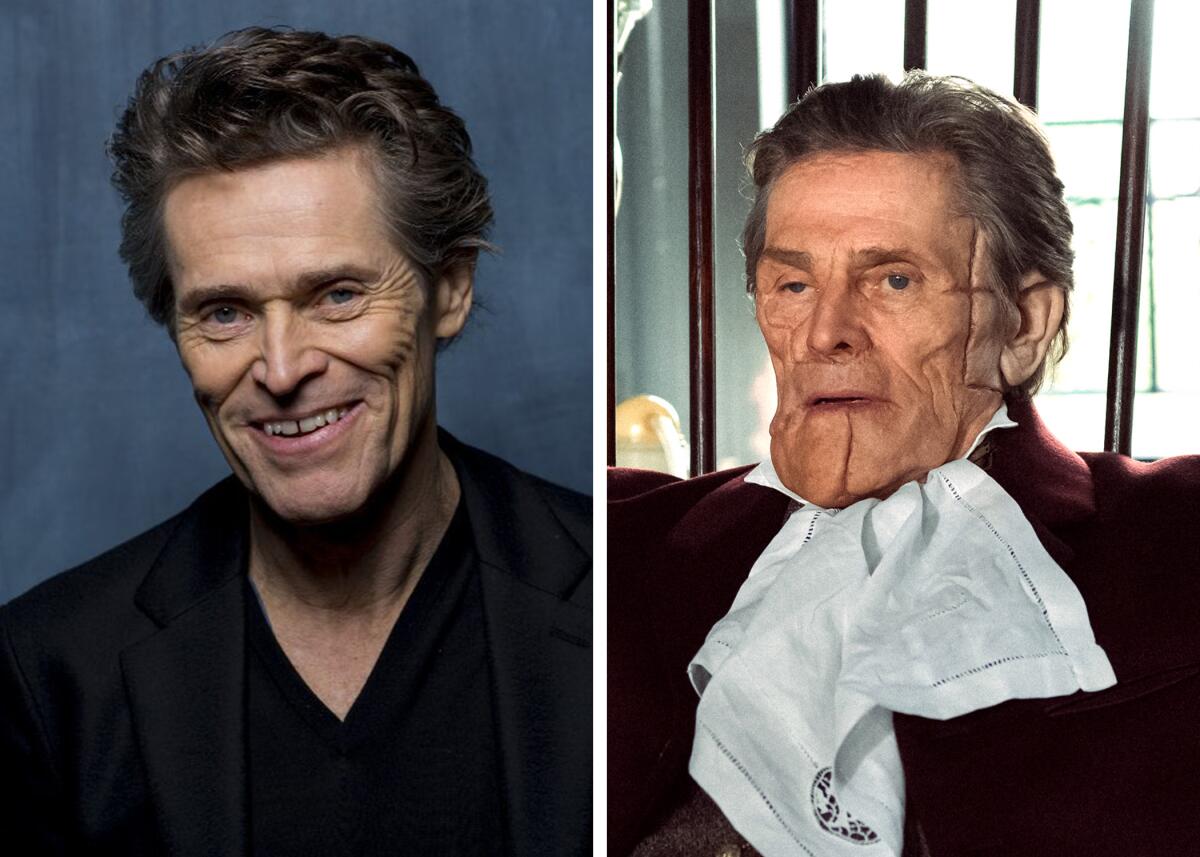

“Poor Things”

Hair, makeup and prosthetics designer Nadia Stacey wanted to be sure viewers of “Poor Things” could go on an emotional journey with Dr. Godwin Baxter, the film’s mad scientist protagonist. Baxter, himself a surgeon, has been experimentally operated on by his father, so Stacey had to show how he has been both Dr. Frankenstein and the monster.

On being an actor, Willem Dafoe says, “I still love doing what I do, because it’s always different. For me, it always gets deeper. It teaches me things. It’s a beautiful job to have.”

Stacey guided her design of Willem Dafoe as Baxter to show how “he’s been put together like a patchwork quilt of a man,” she said. Half-a-dozen silicone pieces, some prepainted and all made fresh daily, were applied to Dafoe’s ears, jaw and chin area, forehead, thumbs, hairline and one eyebrow, most with vivid scars or deformities.

“His scars need to be kind of perfect” to illustrate that Godwin and his father were skilled surgeons, Stacey said. They lowered an ear to imply that it was once removed and reapplied and made his right jaw sag unevenly to add more distortion.

“You need to feel for him. If the look is too grotesque, it overtakes the way you see the character on screen,” said Stacey, a 2022 Oscar nominee for “Cruella.” She was careful not to obscure too much of Dafoe’s face and apply prosthetics in pieces to allow more natural muscle movement.

With the look established, Stacey and her team could shift to making Dafoe comfortable during the three-hour application process. But there were surprises to come. “We only learned two weeks out that the first 50 minutes of the film was to be shot in black and white,” she said. The change required new makeup tones to make the face read well.

“I do always think with makeup, it needs to be impactful but not that you notice it all the time, even with someone with changes as big as Baxter’s face,” she said. “You almost want to get to a point where you just accept that this is what he looks like.”

“Maestro”

In “Maestro,” star and director Bradley Cooper, 48, had to age nearly 50 years to portray legendary conductor and composer Leonard Bernstein. It fell to prosthetic makeup designer Kazu Hiro to help the actor look younger, older, heavier and more like Bernstein.

Directors Blitz Bazawule (‘The Color Purple’), Bradley Cooper (‘Maestro’), Michael Mann (‘Ferrari’), Alexander Payne (‘The Holdovers’), Celine Song (‘Past Lives’) and Justine Triet (‘Anatomy of a Fall’) on how they do what they do.

When your subject is also your boss, the task could be more difficult, but Cooper was “without a doubt, the best person I’ve ever worked with,” Hiro, a double Oscar winner (“Bombshell,” “Darkest Hour’) and two-time nominee, said via email.

“I designed five distinct stages to depict Lenny’s evolving appearance over the years. For all stages, I incorporated vacuum-formed pieces to accentuate the ear helix and lobe. And [a] silicone nose plug to widen his nose wings.” Computer-sculpted body pads were added for later years.

Here, he breaks down those stages:

(1943-46): “Bradley had prosthetics for the nose, upper and lower lip and chin. I used a silicone string attached to the wig clip, which I secured onto his temple hair, giving a subtle lift to the eye corners.

(1955-57): “This stage retained the original prosthetics but without the face-lift. The wig was positioned slightly higher, and after its application, I added gray shading to the temples.

(1967-71): “This stage introduced prosthetics for the nose, upper and lower lips, chin, cheeks, neck and earlobes. Given the closeness of Lenny’s hairline to Bradley’s, I applied a bald cap, leaving the nape exposed. Hairstylist Lori McCoy Bell blended the wig with Bradley’s natural hair.

(1977-78): “Initially, I designed and sculpted an older look, but Bradley wanted Lenny to appear more youthful and “sexy” during this period, especially since Lenny was dating a younger man. I introduced a forehead piece to the existing Stage 3 look and added old-age stipple around the eyes, along with eyebrow hair pieces. This stage also had scenes featuring mustaches and beards.

(1989): “This comprehensive stage included prosthetics for the top of the head, forehead, eyelids, nose, upper and lower lips/chin, cheeks, neck, back of the neck, shoulders, earlobes, hands and arms.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.