‘Poor Things’ composer Jerskin Fendrix finds there are no lines to cross for this score

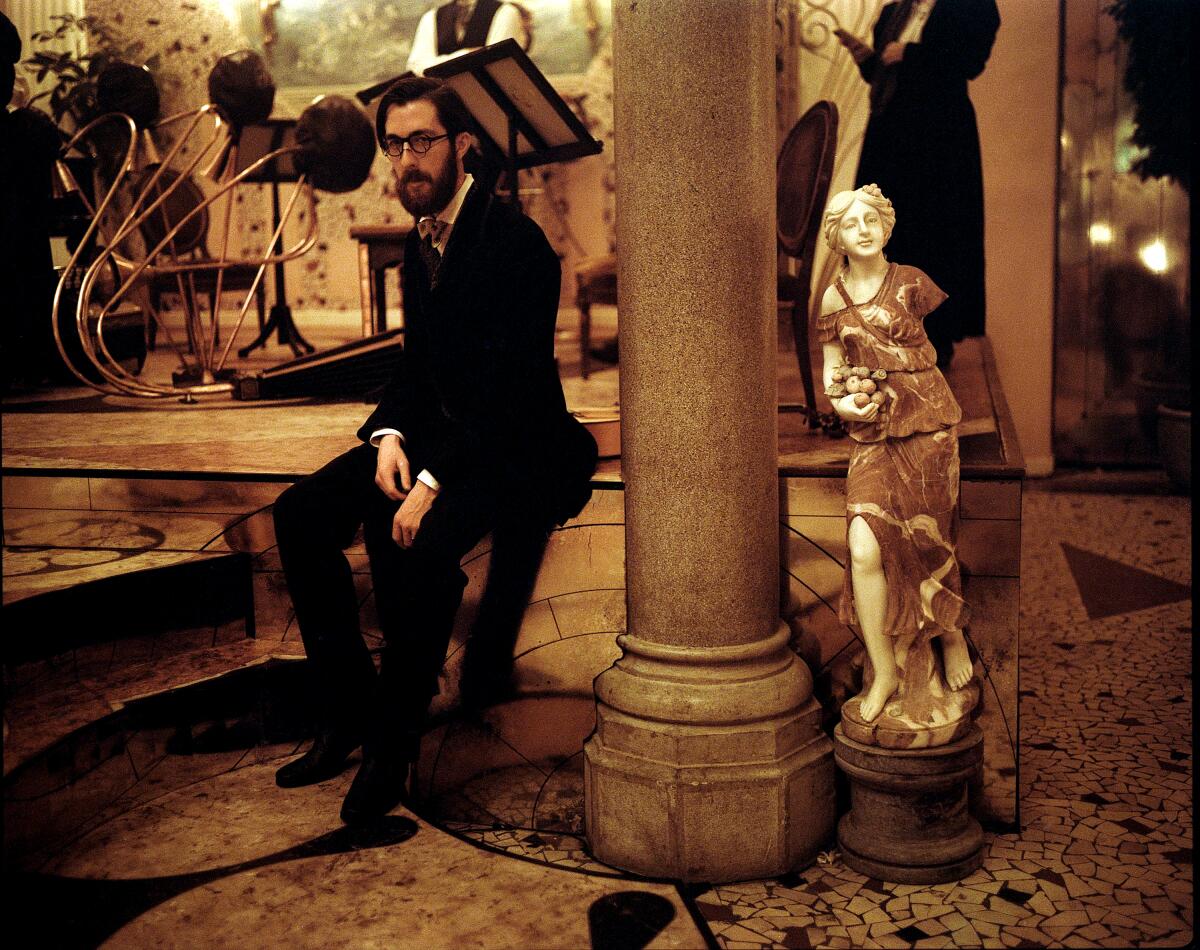

Out of nowhere comes Jerskin Fendrix, the surprise first-time composer of what is arguably the strangest film score of the year: “Poor Things.”

This fractured fairy tale of a woman-child — played to 11 by Emma Stone — with a Frankensteinian backstory and a sudden onset awakening of sexual and moral enlightenment was directed by the quirky Greek auteur Yorgos Lanthimos, and he found an equally outlandish musician to narrate the story — commissioning an original score for the first time in his filmmaking career.

“He’s obviously a very singular artist,” says Fendrix, “and he goes about things in an unorthodox manner. I think one of the reasons his films work so well is that there’s something very subversive about how he chooses all of the elements that build up a film. And for him to have this really big project with Searchlight, and then decide to choose someone who’s basically just released an album of dumb pop songs to do it — there’s something kind of mischievous in that.”

The idea of manipulated flesh is reflected in the pinky skin tones and clothing surfaces and silhouettes that recall body parts, which costume designer Holly Waddington cleverly exploits.

“Jerskin Fendrix” is a stage name for Joscelin Dent-Pooley, 28, who grew up in the English countryside of Shropshire on an eclectic diet of high church music and ’90s Disney animated films and rap. He studied classical at Cambridge, where he wrote and performed music for theater — including a play starring future “The Crown” player Emma Corrin. After school he made an experimental opera, then started writing and performing “dumb pop” songs — which were in fact highly intelligent, off-kilter and surprisingly emotional songs that he released as an album, “Winterreise,” in 2020.

Lanthimos discovered that album as he was preparing the wildly steampunk storybook world of “Poor Things,” and the two artists met and connected over a shared impulse of subverting expectations by using humor and exaggeration. Fendrix was engaged six months before principal photography began, and he wrote 95% of the eventual score inspired purely by Tony McNamara’s script and the film’s concept art and set designs.

“It’s kind of like a visual aneurysm,” says Fendrix, “the designs were pretty much like what you see in the film — just so much color and depth and real, unprecedented levels of creativity. So, in different ways, both the script and the artwork kind of let me know exactly what the film was going to be, basically, and how far I had to push everything.”

Right away Fendrix decided not to compete with the scale and ornateness of the visuals, and instead focus more on the interior emotions of the characters — namely Stone’s Bella Baxter, the product of a mind-boggling brain transplant.

He wrote wobbly, childlike music for the infantile Bella — messing with instrument tuning and asking his other musicians to “play stupid,” then manipulating the recordings to warp them even more. For all of the surgical and biological horrors in the film, Fendrix wanted to play up the cuteness and naive, vulnerable feelings that are often more awkward than polished.

Because the film deals with death and reanimation, Fendrix favored instruments that rely on human breath — flutes and oboes — as well as ones that are animated mechanically — pipe organ, bagpipe, accordion — that he then attempted to bend in a way that imitated human speech, which created “a really unnerving effect,” he says.

The story plays out in chapters — demarcated by changes in setting and Bella’s personal evolution — and the score progressively moves from very simple ideas to a more complex harmonic language. In his review of the film, The Times’ Justin Chang singled out Fendrix’s “unruly, dissonant score,” which “plays like something piped in directly from Bella’s transplanted psyche. In a way, Fendrix’s compositions — moving from the wry, picaresque strings of Bella’s early years to a convulsive coming-of-age synth-ony — tell the story as directly as any of McNamara’s words.”

All of the music Fendrix was conjuring, simply by ruminating on the story in his mind, was so off-kilter, so un-Hollywood, that he was stressed about it for the first few months as he sent each piece to Lanthimos.

“Each time I would think: oh, is this too weird a noise to be used in this, like, massive Searchlight film?” he says, “and seeing where the line would be. In the end, there was no line.”

As strange and explicit as “Poor Things” is — with its Victorian medical body horror and anti-Victorian body sensuality — for Fendrix it came down to something very pure.

“It’s such an interesting film, emotionally,” he says. “You basically have a format where someone is experiencing these really exaggerated things for the first time — they’re falling in love, and sex, and seeing violence for the first time, and horror, and famine — and being able to not just have this huge array of emotions, but know how concentrated they must have felt.”

His aim was to write music that reflected “a searingly concise expression of Bella’s feelings, and peoples’ feelings and reactions to Bella, and how intense they were.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.