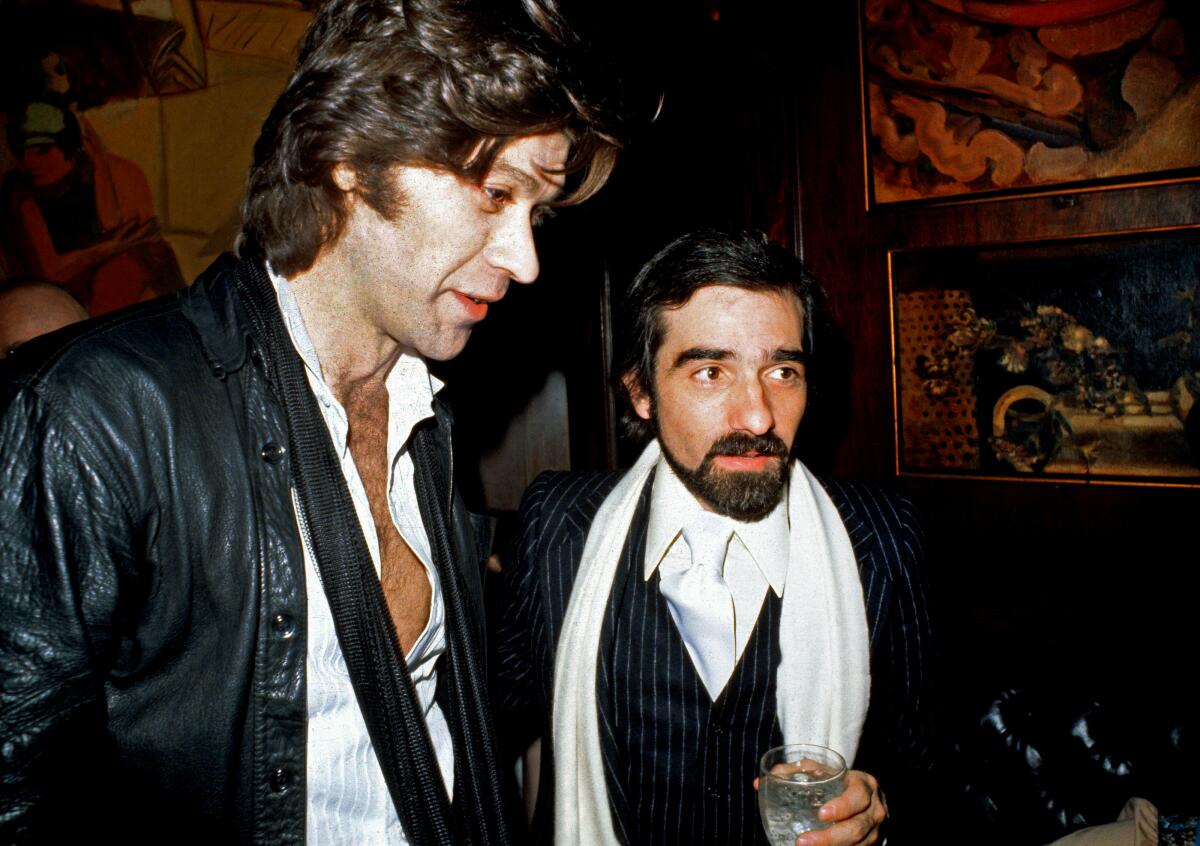

For his final work, with Martin Scorsese, Robbie Robertson found a personal connection

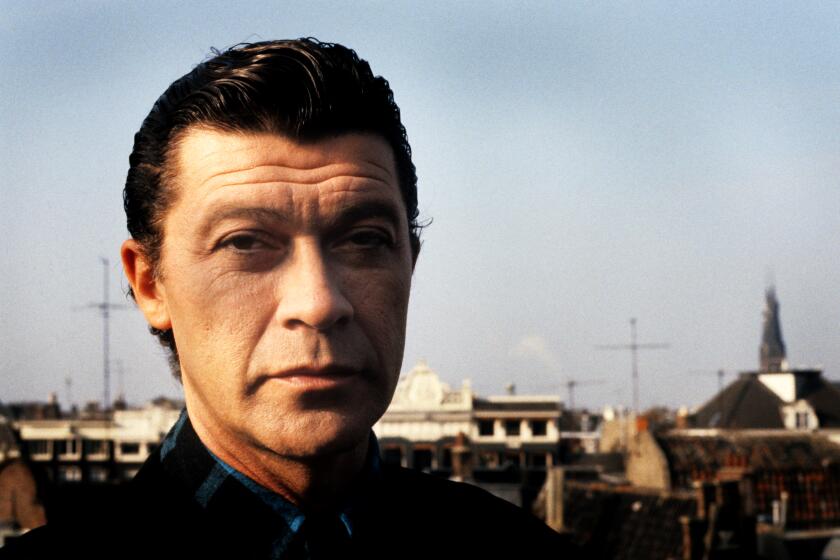

Robbie Robertson made his masterpiece, then left this world. The singer-songwriter-composer spent the better part of a year writing and recording a score for Martin Scorsese’s epic “Killers of the Flower Moon” — all while suffering the effects of cancer. He finished the job and was able to enjoy a private album release party, but he died shortly after in August at age 80.

I was actually supposed to interview him that week. My article became a tribute.

What turned out to be Robertson’s swan song was one of the most impressive scores of the year and the best film score of his career. It was also a fitting bookend to “The Last Waltz,” the 1976 concert documentary about the Band — his band — that introduced him to Scorsese.

“About 10 years ago, Robbie reminded me that the [‘Last Waltz’] project as we conceived it was absolute madness,” Scorsese says by email. “No one had even attempted such a thing. And that really united us. Our friendship began in a deep shared commitment to our chosen art forms — music and cinema, and to ‘walking through the fire,’ as Robbie used to put it, and coming out on the other side with something we could be proud of.”

A look back at the best of Robbie Robertson, the pioneering Band songwriter and guitarist who died on Wednesday at 80.

Robertson became one of Scorsese’s “key collaborators,” musically supervising and contributing original songs or instrumentals on multiple pictures through the years. He scored “The Irishman” for Scorsese in 2019 — but “Flower Moon” was an even more personal and perfect assignment for Robertson. He was a descendant of Mohawks, and this was a story of the Osage and their victimization in Oklahoma a hundred years ago.

“It was what made it especially important for him, especially meaningful,” says Scorsese. “I’m so happy we got to do it together.”

Still, Robertson didn’t want anything stereotypical on the score.

“He didn’t want to do the obvious kind of thing, the kind of Hollywood approach to Native American music,” says Mark Graham, the orchestrator who helped Robertson achieve the score. “He was very cautious about that. And when you see the movie open, you don’t really know what the story is at that point — the audience doesn’t — and to hit it with a kind of dirty rock guitar, that’s a bold move.”

Robertson couldn’t read or write music, and he was not a traditional film composer. He was initially reluctant to being set up with Graham, a veteran music man who works with such renowned composers as John Williams and Alexandre Desplat, but the two men soon found a groove. Starting in July 2021, Robertson would send Graham iPhone videos of him strumming or singing ideas. Some were conceived for specific scenes, others were just moods he wanted to create from his conversations with Scorsese — everything from dirty rock to blues to a Salvation Army-style brass band.

“Robbie had this idea about an ensemble that we haven’t heard for a film,” says Graham, who remembers Robertson being particularly obsessed with the manzarene, a jangling zither-like instrument he discovered on an old blues record, as well as some unusual guitar bows. “We had this weird guitar ensemble,” says Graham, “with lots of different guitars and mandolins, mandocellos, a zither, some keyboards — all old-fashioned stuff — bass, some percussion, a couple of cellos and a harmonica.”

This unorthodox band assembled at Robertson’s longtime studio home at the Village in West L.A. Robertson was tough on his musicians, reacting very strongly if he didn’t like a take. “The worst thing he could say was it was ‘really ordinary,’ says Graham. “You couldn’t really define what ‘ordinary’ was. You would fuss with stuff and kind of arrive at something that he felt was good.”

Robertson recorded hours of music in this band-like way, adding native flutes and shakers and all kinds of other earthy elements, and sent it to Scorsese and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who would cut it in as they pleased. Much of it didn’t end up in the picture; some of it was used over and over. But Scorsese mixed it loud, and the music became a dominant character — a ghost, a heart and a time machine all in one.

The two opening sequences — of a black and white newsreel providing backstory about the oil boom that made the Osage rich, and Leonardo DiCaprio’s introduction to the town of Fairfax — strut with a confident, bluesy gait that establishes a feeling of upbeat pride that will soon be upended.

For a scene where Ernest (DiCaprio) drops off Mollie (Lily Gladstone) in his cab, “I told him I wanted something ‘dangerous and fleshy,’” Scorsese says. “He gave me a real gutbucket blues theme that not only worked for the scene, but drove the momentum of the picture. I asked for another theme that matched the scale of the landscape, the mystery. He gave me that and more.”

As the Osage deaths start piling up, Scorsese uses a sickening, arrhythmic heartbeat idea that insistently thumps under the slow reign of terror with agitated harmonica solos.

The film runs a staggering 3.5 hours, and “with a picture that big in scope, with that many characters and locations and relationships and betrayals,” Scorsese says, “the music helps to keep everything unified and moving forward. In order for that to work, it really needs to become a key aesthetic element. And for that, you need an artist as great as Robbie was.”

Scorsese adds: “We just knew each other. We trusted each other. We respected each other. We loved each other.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.