‘Stolen Youth’ chronicles a years-long reign of abuse of young people by a cult leader

Like many who read it, Zach Heinzerling was stunned by a 2019 New York magazine article that exposed the bizarre, cult-like control asserted by an ex-convict named Larry Ray over a group primarily of Sarah Lawrence College students he met in 2010, when he became an unexpectedly permanent guest at his daughter’s on-campus housing.

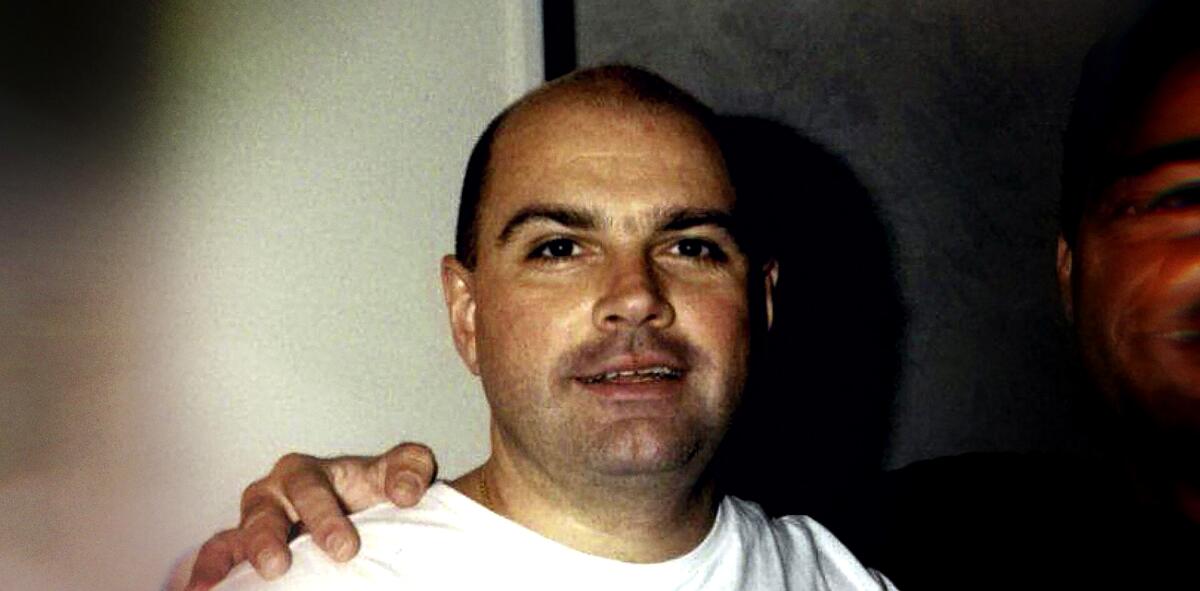

“The article was almost too shocking to really digest,” the filmmaker said. The piece, by journalists James D. Walsh and Ezra Marcus, described a terrifying, years-long reign of abuse conducted by the manipulative Ray over the group, which he had effectively brainwashed as they migrated with him from campus to an Upper East Side Manhattan apartment that became a physical and psychological torture chamber. In January, Ray, now 63, was sentenced to 60 years in federal prison. The 15 counts included sex trafficking, racketeering and forced labor.

Heinzerling, an Academy Award nominee for the 2013 documentary “Cutie and the Boxer,” tries to make sense of the case, which he revisits in the Hulu docuseries “Stolen Youth: Inside the Cult at Sarah Lawrence.” His approach differs from the often exploitative tone that characterizes much in the true-crime genre.

The director was guided by “the desire to humanize a story and also provide a place for empathy for these individuals who I think after the article were kind of blamed in some way [by a] ‘How could you let this happen?’ response,” he said. “It seems so unthinkable that someone like Larry could have so much control over these bright, promising individuals.”

Across three hour-long episodes, relatively concise by streaming standards, the filmmaker explores the question and deals with some inherent challenges.

“There’s a lot of room for growth in our culture of understanding coercive control,” Heinzerling said. “One of the hard things about this project was, how do you put someone back in this state of 18 or 19 years old, where you’re really not an adult and you’re still figuring things out and you’re very impressionable? And then, how do you show a version of Larry that they met through their eyes, without any archival [material] or footage of him or credible sources for his back story?”

His entry point was one of the survivors, Daniel Levin, who in 2021 published a memoir about the experience — “Slonim Woods 9,” the number of the campus apartment he shared with other students who would come under Ray’s command — had reached out to Heinzerling in the article’s wake.

“What Larry did was control our stories and our ability to tell our own stories to ourselves about what our lives were,” said Levin, who now shares his experiences as he teaches continuing education students how to turn their own troubling memories into narratives. He shared a recent Zoom conversation with a fellow survivor, Felicia Rosario, who was a medical student in Los Angeles when she met Ray through her brother Santos and sister Yalitza, who also were in the group.

Once the story broke, Levin said, “suddenly there were a lot of people with a lot of power and a lot of money who wanted to control our stories. I was, as far as I knew, the only person who had any ability to do anything about that.”

Heinzerling relied on archival videos and audio recordings from his subjects, including Ray, whom the filmmaker met with before he was indicted, as well as material made public as evidence in the trial. “Most traumatic narcissists are very interested in telling you their side of things,” said Heinzerling, whose work with Beyoncé on the 2013 web series “Self-Titled” appealed to Ray’s vanity, according to Rosario. “He was eager to defend himself and rail on about the conspiracies that were ruining his life.”

Rosario was involved in a relationship with Ray, as was a second woman, Isabella Pollok, who was sentenced to 54 months in federal prison after pleading guilty to conspiracy to commit money laundering. Heinzerling visits the women, the last members of the group to remain at the suburban New Jersey home they shared with Ray, right after his 2019 arrest when they were very much caught up in the chaos.

“It is hard to watch because I was so in it,” said Rosario, who has since rebuilt her life, and her relationships with her two siblings and their estranged parents — a process that the series thoughtfully captures in its final episode. “Not in a ‘brainwashed’ way. I was so afraid, I was afraid of what Larry would do to me if I did tell the truth.”

The disturbing scenes serve as a marker on a path to recovery. “It’s actually really great to watch because it feels really good being on the other side,” Rosario said. “It’s like, ‘Wow, I made it out of there, you know?’ That’s really satisfying.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.