Hulu’s ‘The 1619 Project’ examines the impact of slavery on America today

In early 2019, New York Times reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones made a simple pitch to her editors. The year marked the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first Africans to the English colony of Virginia, an event generally regarded as the beginning of American slavery. Hannah-Jones suggested a project to examine the impact of slavery on American society and the ways in which that impact lingers to this day. In August of that year, the New York Times magazine published the 1619 Project, a collection of essays, written by multiple authors, combining journalism and history that addressed the subject from various angles.

At which point all hell broke loose.

Embraced by many readers, the project also provoked apoplectic responses from some historians, who took issue with Hannah-Jones’ handling of slavery and the American Revolution, and from right-wing politicians and their followers, who objected to the very idea that the effects of slavery could possibly impact the way we live now. President Donald Trump publicly attacked the project, and state legislatures proposed bills to strip federal funding from schools teaching it. The project was born into a world of rising white supremacy and white nationalist rhetoric. Hannah-Jones received death threats.

As her history of Black America comes to Hulu, journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones opens up about feeling ‘exposed,’ upsetting conservative politicians and more.

Today, as “The 1619 Project” lives a new life as a series on Hulu (with Hannah-Jones as star/narrator and a producer), its architect still can’t quite believe it all.

“When I was in the eye of the storm, when the attacks were the worst, I wasn’t responding well,” Hannah-Jones says in a recent video call. “It’s been a hard four years in many ways, but now I’m at a point where I realize all the attacks just made the project grow and expanded its reach.”

Indeed, the project spawned a podcast and a book, published in 2021. Despite opponents’ efforts, it did enter school curricula. But a TV show? Hannah-Jones still sounds a little stunned.

“It’s frightening to turn your work into a medium that you don’t have expertise in,” she says. “I am an old-school print reporter. This is not a medium I ever thought I would work in. But clearly I understand the power of television and streaming and the potential to reach so many more people than you’ll reach with a book full of 10,000-word essays. I’m a 1619 evangelist, and I did this project because I really do feel like our nation needs to grapple honestly with its past and how its past is shaping our present.”

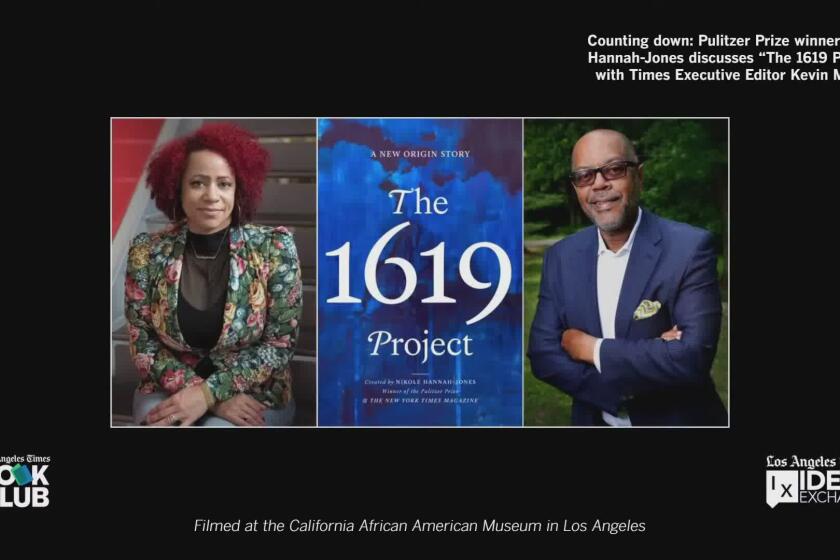

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones discusses “The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story” with L.A.

Sporting her trademark red hair and palpable sense of purpose, Hannah-Jones is clearly proud of the series. Divided into six episodes, with subjects ranging from music (featuring a freewheeling conversation between Hannah-Jones and two-time-Pulitzer-winning culture critic Wesley Morris) to capitalism, “The 1619 Project” furthers the original project’s mission of exploring the racism on which the country was built, and connecting the power dynamics of slavery and Jim Crow to those of the present day.

For instance, the episode devoted to the subject of fear begins by looking at slave patrols, organized groups of armed men who tracked and disciplined slaves in the antebellum South, and makes the connection to armed vigilantes and today’s surging reports of police violence against Black men and women (a connection KRS-One set to a killer beat in the 1990 song “Sound of da Police”). It also flips the script and looks at white fear of Black progress and equality.

It is a provocative approach, but one that executive producer and director Roger Ross Williams sees as necessary.

“Many of the issues we face as a country stem from our negligence in dealing with slavery’s effects, and so its impact still looms over us hundreds of years later,” Williams says via email. “I believe ‘The 1619 Project’ is required viewing to understand what it means to be a citizen of this country and how we can improve the American condition. If we improve the lives of Americans and face the complicated history of our past, I believe we can change our future for the better.”

Hannah-Jones knows the original 1619 Project contained errors, to which she and her editors responded and which were then corrected in the book version. Any project of this size and scope will lead to some corrections. She also knows some critics used the mistakes as an excuse to discredit the entire project, which she stands by fervently.

“I don’t know how anyone can argue that the year slavery was introduced into the colonies is not one of the most important years in American history,” she says. “We almost lost our country over that issue in the Civil War. And we can look at our society today and see the racial polarization and the racial divide that we have and know how important 1619 always was.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.