‘Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris’: When the costumes should get equal billing to the stars

Tasked with re-creating midcentury Christian Dior couture for director Anthony Fabian’s “Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris,” Oscar-winning British costume designer Jenny Beavan did the job one better, turning a multitude of sumptuous gowns in deep reds, emerald greens and other eye-catching colors into a kind of starring role all their own. The film, an adaptation of the book “Mrs. ‘Arris Goes to Paris,” sees Lesley Manville as the widowed title character, a financially strapped housekeeper in post-WWII England who falls in love with a Dior gown and dreams of owning one herself. In a string of both lucky and unlucky events, Ada Harris finally saves up the money and travels to Paris, where Beavan’s work takes center stage.

It’s a story in which dreams can and do come true, and a reminder that inner beauty is really what makes people shine.

I read where you said, “The last thing I’d be inspired by is a Dior gown.” Someone might wonder how you got involved in the project.

In a way, I’ve never been interested in fashion; I’m all about storytelling with clothes. But the story of Dior is amazing, and when you start to look into the gowns, of course, they’re absolutely stunning, particularly in the ‘50s. They’re so beautiful, and the shapes are so wonderful. So I can become very interested in them once I’ve made a reason to be. The whole story of the film is about wanting a Dior gown. I was probably a little bit short to have said it that way.

I know you went into the Dior archives, and there was a minor detail that got lost in translation: You thought Dior, themselves, would create the dresses, but it turned out not to be the case.

Yes. I was totally given to understand I would [partner] with Dior and that Dior would be doing the Dior part. In your dreams!

Ouch.

That came up as I thanked them profusely at the end of the [archive visit] saying how wonderful it would be to be working alongside them. Four horrified faces looked up at me and went, “non.”

After the initial shock, I said if it’s up to me I do know people who will be able to create Dior, but it will cost a lot of money; there were producers there, and I thought it best it come out in the open. But we did it, and I’m very, very proud of what it looks like.

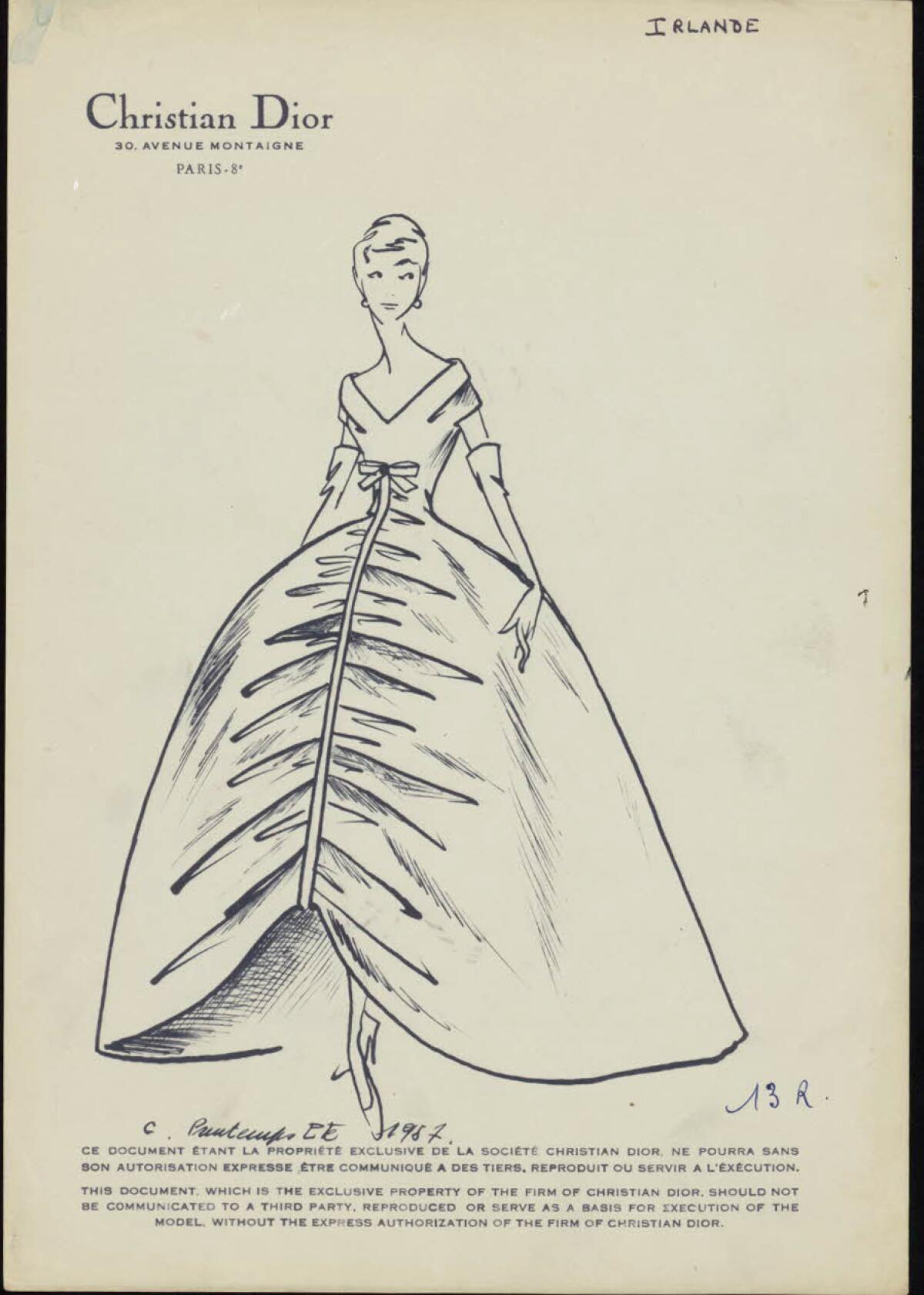

How many Diors based on the original sketches were in the film?

In all, there were three dresses I actually created and five that Dior lent us from their Heritage Collection, which is not the original ‘50s pieces but pieces Dior has remade. We got up to about 20 outfits for the show. All of them were absolutely recreated from photographs and the information I got from the Dior archives of that 1957 show. The famous Bar Suit was from ’47, but it used to come out from time to time, so it was OK to have it in the show.

So no original 1957 Dior piece?

We had one dress, Puerto Rico, that we got from Cosprop in London on the racks. The inside was stripped out, but it was verified as a Dior original. Gorgeous dress. In fact, Dior house said it was one of the most popular dresses that would have been made. I think because it was so wearable and being in a cotton it was not so expensive; it was a very central but beautiful dress.

Tell me about the Temptation dress.

Temptation is based on something I saw in the archives that was hand-sequined all over. I went with the not-too-bright-in-your-face claret red color. I thought it would suit Lesley Manville, it would suit Mrs. Harris, and it would suit Alba Baptista [as model Natasha] when she wore it in the fashion show.

Did you create the color with dye?

No, I was looking for something that sparkled. I found the fabric online up north in England. We think it came from India or Pakistan, and it was actually relatively cheap. We added sequins to it but also put a stronger red behind it. Three characters had to want to wear it — Natasha, [customer] Lady Dant and Ada Harris.

The central floral pink Dior dress Mrs. Harris originally fell in love with, the Ravissante, now that is a piece of art.

The whole thing with costume is it has to be utterly appropriate for the character, it had to look good on Lady Dant and Mrs. Harris and yet never worn. That really presented a challenge, because normally it’s when someone puts a dress on that it comes to life and you understand it. But that dress is never worn. It’s the real killer, because it’s the one that sets the whole story off. But nobody actually puts it on.

What were the fittings with Lesley like? This was during COVID?

It was so collaborative. I absolutely love her and have worked with her before. She loves clothes, and she’s a great clothes horse. She just came in and looked at the rack and said, ‘Oh, gosh, yes.’ I mean I grew up in London in the ‘50s, and I remember women wearing those wraparound apron-type pieces.

Were Mrs. Harris’ everyday clothes all vintage?

Absolutely. I think every single piece in the England settings was vintage. I think we made only the coat.

What was the difference between creating clothes for postwar England and then postwar France?

It’s interesting, because France — even though they were occupied — seemed to keep more clothes and be more stylish. Here in England, where we were not occupied, we got very drab and dreary. Obviously, you can’t afford to import things, so the British naturally had to use and wear what they could make in England. Also, story-wise in France [we see] more upscale groups of people to start with versus in England. Now Vi, the Caribbean character and Ada’s good friend, brightened it and brought some life to it all.

Do you plan to work until you can’t, like costume designers Ann Roth and Albert Wolsky?

Oh, yes. Isn’t it brilliant that we don’t have to stop because of our age? I don’t quite know what I’d do if I didn’t.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.