Why the filmmakers behind ‘Living’ — a tale of life’s end — had younger folks in mind

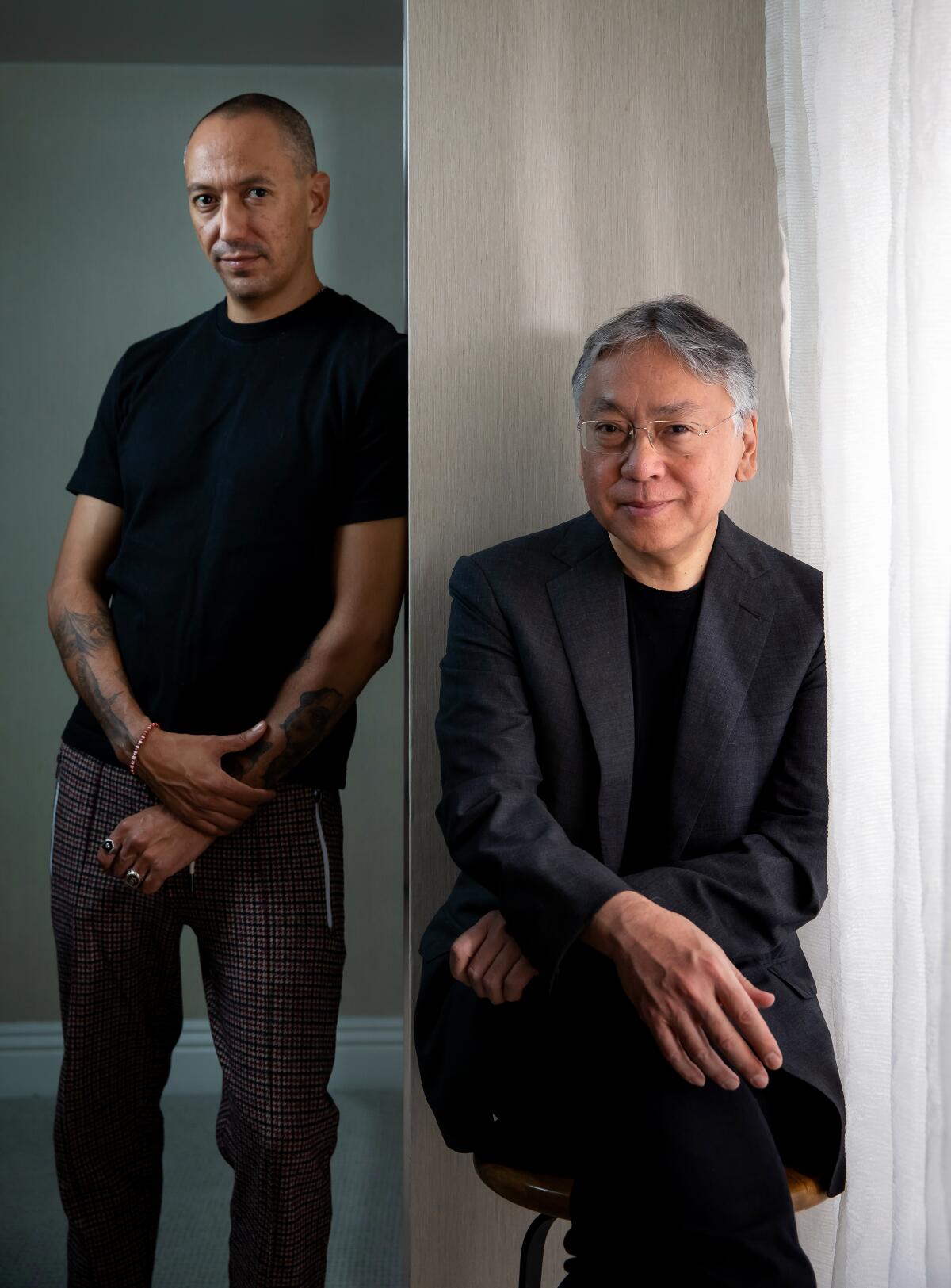

Reimagining Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 film “Ikiru” (or “To Live”) had been on the mind of Nobel Prize-winning novelist Kazuo Ishiguro (“The Remains of the Day,” “Never Let Me Go”) for more than two decades, and it was during a dinner with eventual “Living” producers Stephen Woolley and Elizabeth Karlsen where the idea started to coalesce.

Born in Japan, and having lived in Britain since a young lad, Ishiguro notes the Kurosawa films he saw growing up shaped the acclaimed novels he went on to write. “I had been thinking, wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could have a new version of “Ikiru” and somehow marry it to Englishness and the English Gentleman, almost as a metaphor, a study of the human condition,” says the author. “We all have a bit of English Gentleman in us. It’s a certain attitude you have when you have to face up to the emotions and difficult things in life.”

“Ikiru” is a contemporary film (influenced by the Russian novella “The Death of Ivan Ilyich”) that comes on the heels of World War II. It follows Mr. Watanabe (Takashi Shimura), a terminally ill bureaucrat and his last efforts to do something meaningful with his life. “Living” diverges in more ways than one, leaning in as a stylistic and conceptual period piece set in London, with Bill Nighy playing the cancer-stricken character, Mr. Williams — a casting suggestion Ishiguro made from the get-go.

Writing the character for Nighy made “things easier in some ways, and in others, made them harder,” Ishiguro tells The Envelope. “Every time I imagined a scene of dialogue or a gesture, I would imagine how Bill would do it. Even the name Williams I chose is a version of Bill’s first name.”

Six Oscar contenders -- Austin Butler, Paul Dano, Brendan Fraser, Jonathan Majors, Bill Nighy and Adam Sandler -- talk about family, playing real people ... and mortality.

A key theme that emerged in the script process, which was developed with South African director Oliver Hermanus (“Moffie”) over months of video calls during the pandemic, was hopefulness. “The original was written at a time when Japan didn’t know what lay ahead. Cities were shattered from a disastrous war, and for me, Kurosawa was pessimistic if Japan could turn it around,” Ishiguro says. “Oliver and I have the benefit of hindsight and thought our movie could be a bit more optimistic in terms of its legacy where the younger generation would see this and take it somewhere good.”

Filling the youthful role were the characters of Margaret (Aimee Lou Wood) and Peter (Alex Sharp), which sees a love story blossom. “We knew Margaret and Peter were the next generation,” Hermanus adds. “And with Peter, he was going to take the lessons the Williams character has to offer and give them new energy.”

Visually, Hermanus was inspired by the moody, monochrome palette of “Ikiru” and followed a parallel two-tone tapestry but in color. The walls of the sets, especially the London County Hall office where Mr. Williams works, were done in rich blacks, while the men wore dark navy and charcoal hues. The only hints of color and lightness peeking through were from Margaret and the white papers scattered about their desks.

Framing was deliberate, honest and forthright. The composition pulls you in, further commenting on the deepening story and emotions of the characters with moments slightly off-center frame, as when Mr. Williams confesses to Margaret he has cancer, which subliminally swells his internal monologue. Others brought scale to the period piece with characters playing against iconic London architecture.

And then there’s Nighy, who says more with a look than some ensemble casts say in entire films. There is a poignant scene, where Williams is sitting on a couch having just received his diagnosis, waiting for his son to arrive home. Williams wants to share the news, but his son and daughter-in-law can’t be bothered. Hermanus added to the vulnerability of the conversation by framing the back of Williams’ head. “A conceptual influence for me, in terms of Bill’s character, was [American realist painter] Edward Hopper. His work is single-frame, but it tells a story of isolation and loneliness. And a real sense of being in a big city but being very much hidden and unseen,” the director says.

“Living,” opening this week, also plays larger moments with restrained character commentary, which strays from the original picture, as with the climactic scene with Mr. Williams on the swing. “I knew I wanted his expression to be small, a real minimal sense of satisfaction,” Hermanus says. “It’s the only way it moves out from being sentimental and moves into a space where it’s actually emotional.”

It’s in these subtle, emotional moments of self-reflection where death affirms life and mortality is questioned that “Living” shines. “This is why I thought the marriage of this material could be an inspiration for people who watch it,” Ishiguro says. “It could become a kind of celebration of life, where whatever kind of humbling, stifling hand you’ve been dealt by life, that there’s still a chance you can turn it into something wonderful and magnificent.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.