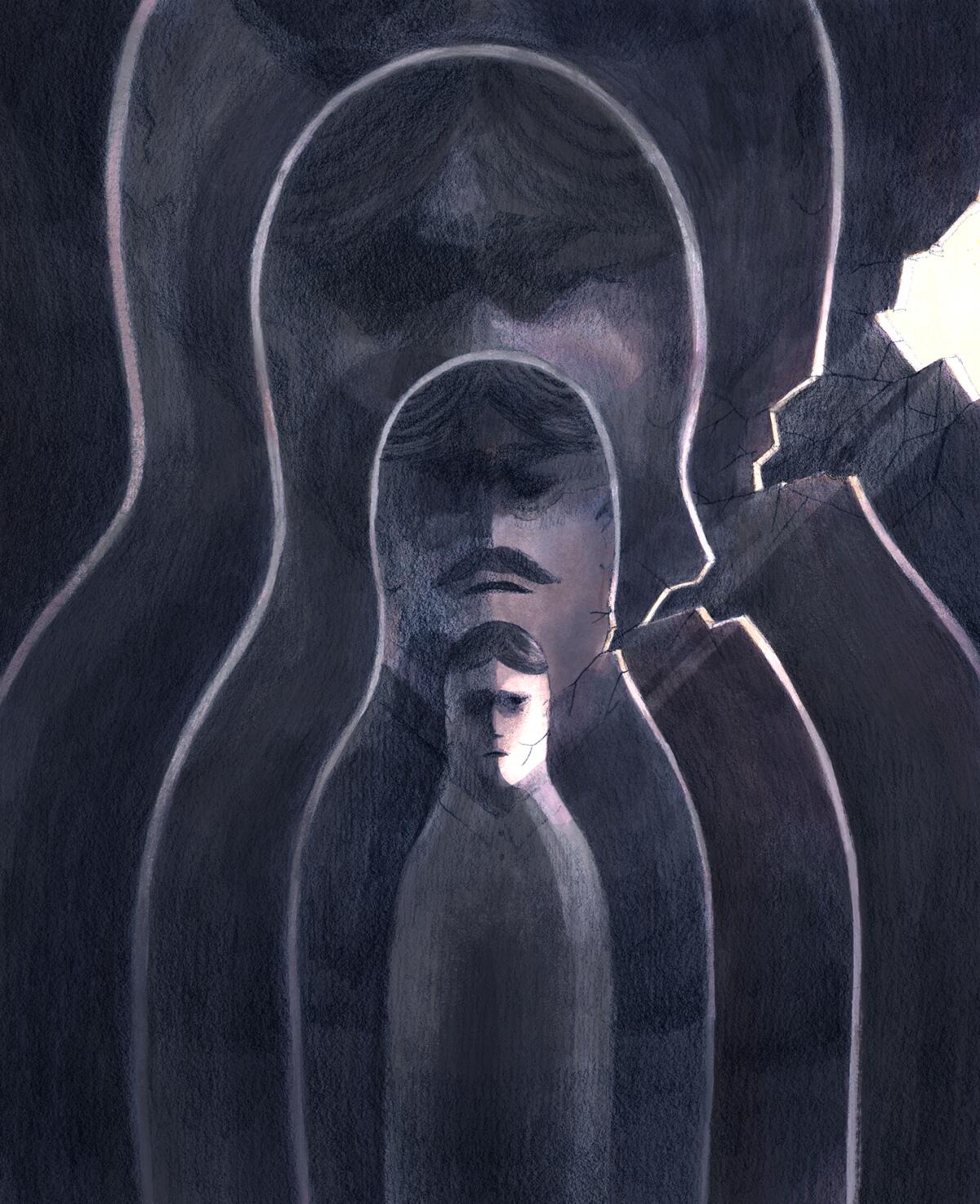

These damaged film dads unleash trauma on their children

A child grappling with paternal imperfection has forever made for spellbinding drama — though such stories can be wildly different in the telling.

“It’s such a fundamentally human experience,” says playwright and screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter (“The Whale”). “It’s universal but hyper specific, which all good stories are.”

“It’s the most elemental of human relationships, with the possible exception of the youngster and their mother,” adds writer-director James Gray (“Armageddon Time”). “[Mom]’s the first person you meet in life. And usually, No. 2 is Dad.”

“The idea of trauma being passed along from parent to child is interesting in what you inherit, both positively and negatively,” says writer-director Charlotte Wells (“Aftersun”).

“One of the themes I really wanted to explore is that circle of pain and how to break it,” echoes playwright and writer-director Florian Zeller (“The Son”).

“At a certain point in childhood, we realize our parents are just people,” concludes writer-director James Morosini (“I Love My Dad”). “I think we’re disappointed by that, and for a moment, we kind of hate them for it. A big part of coming into adulthood is realizing they’re just people and they’re flawed.”

This fall, these five filmmakers’ releases revolve around flawed fathers. The Envelope spoke further with each of them to break down their approach to creating damaged dads.

“Aftersun”

Father-daughter: In an attempt to decipher the enigma of her loving but sorrowful father, Calum (Paul Mescal), adult Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall) pores over old photographs and home movies from the last vacation she had with him as her 11-year-old self (Frankie Corio).

The flaw: “Calum is better at being a father than he is at just about anything else in his life,” Wells says. “He has set standards and ambitions for himself that he may never be able to attain, and I think that leads to a constant sense of disappointment.” Father then projects those onto his daughter. “He has expectations of her, intellectually, that are unreasonable for her age and assumes her to be more mature, emotionally, than she is.”

The catharsis: “I needed the excuse to dig through my own past,” continues Wells, who delved into old family holiday albums for inspiration. “That’s why I started out making [the film] in the first place.”

“Armageddon Time”

Father-son: In 1980 Queens, New York City, artistic young high schooler Paul (Banks Repeta) endeavors to be truly understood and embraced by his short-tempered, working-class dad, Irving (Jeremy Strong).

The flaw: “He’s inept at parenting,” Gray says of Irving Graff, who’s based on Gray’s own father, who died from COVID while his son was in the midst of editing the film. “I don’t blame [my dad]. I loved him to pieces. But he didn’t know what to do. He didn’t know how to parent. He never read a book about it, never went to see a therapist. He had his rules he learned from his father, which were maybe his father’s sins, and he handed them down to me.”

The catharsis: “I really don’t know, because I’m still sort of in it,” Gray notes. “I don’t know if I’ll ever achieve any kind of catharsis from it. Maybe I shouldn’t … I think the idea of catharsis in art is valid but in our lives is a bit of a fiction.”

“I Love My Dad”

Father-son: In a story inspired by the filmmaker’s own life, estranged father Chuck (Patton Oswalt) does the worst thing for the best reasons when he catfishes his son Franklin (Morosini) as a way to reconnect with him.

The flaw: Morosini feels both Chuck and Franklin are dishonest. “Franklin is dishonest with himself, in a sense, because he’s willing to go along with this thing even though, somewhere in his mind, he knows something’s not right. In the end, he comes around to understanding his dad isn’t a bad person, he’s just a flawed person who doesn’t have the tools to navigate a complex relationship,” he says. “Through their dishonesty, they almost discover something more honest.”

The catharsis: “Making this movie allowed me to explore my dad’s perspective in a way I’d never asked myself to before,” Morosini says. “I was also trying to approach some of my own heavy life stuff with a sense of humor and levity.”

“The Son”

Father-son: Divorced father Peter (Hugh Jackman) enjoys life with new partner Beth (Vanessa Kirby) and their infant son but struggles, alongside ex-wife Kate (Laura Dern), to help his teenage son Nicholas (Zen McGrath) overcome a mental health crisis — all while striving to come to terms with his complicated connection to his own father (Anthony Hopkins).

The flaw: “He’s still obsessed with his past. He’s still obsessed with his pain,” Zeller says of Peter, adding that this inability to forgive his own father for his failings makes it impossible for him to successfully deal with the present. “He’s a tragic character [because] he’s trying hard to avoid being guilty, and this is how he becomes guilty in the end.”

The catharsis: “Gabriel is my eldest of two sons,” notes Zeller, who dedicated the film to his firstborn. “I wrote the play years ago — and made the film — as an act of love for him.”

“The Whale”

Father-daughter: Self-isolated, morbidly obese, formerly closeted father Charlie (Brendan Fraser) strives to finally redeem himself by reconnecting with teenage daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink), whom he abandoned when leaving ex-wife Mary [Samantha Morton] for his new male partner eight years prior.

The flaw: Charlie’s chief transgression is leaving Ellie behind. “It’s complicated,” Hunter stresses, “because he wanted to be part of her life and Mary refused.”

The catharsis: “That emotion of desperately trying to save your kid is so real for me right now in a way that was a little more intellectual when I first wrote the play,” notes Hunter, who today has a 5-year-old daughter. “It’s such a gift that I got a second crack at telling this story.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.