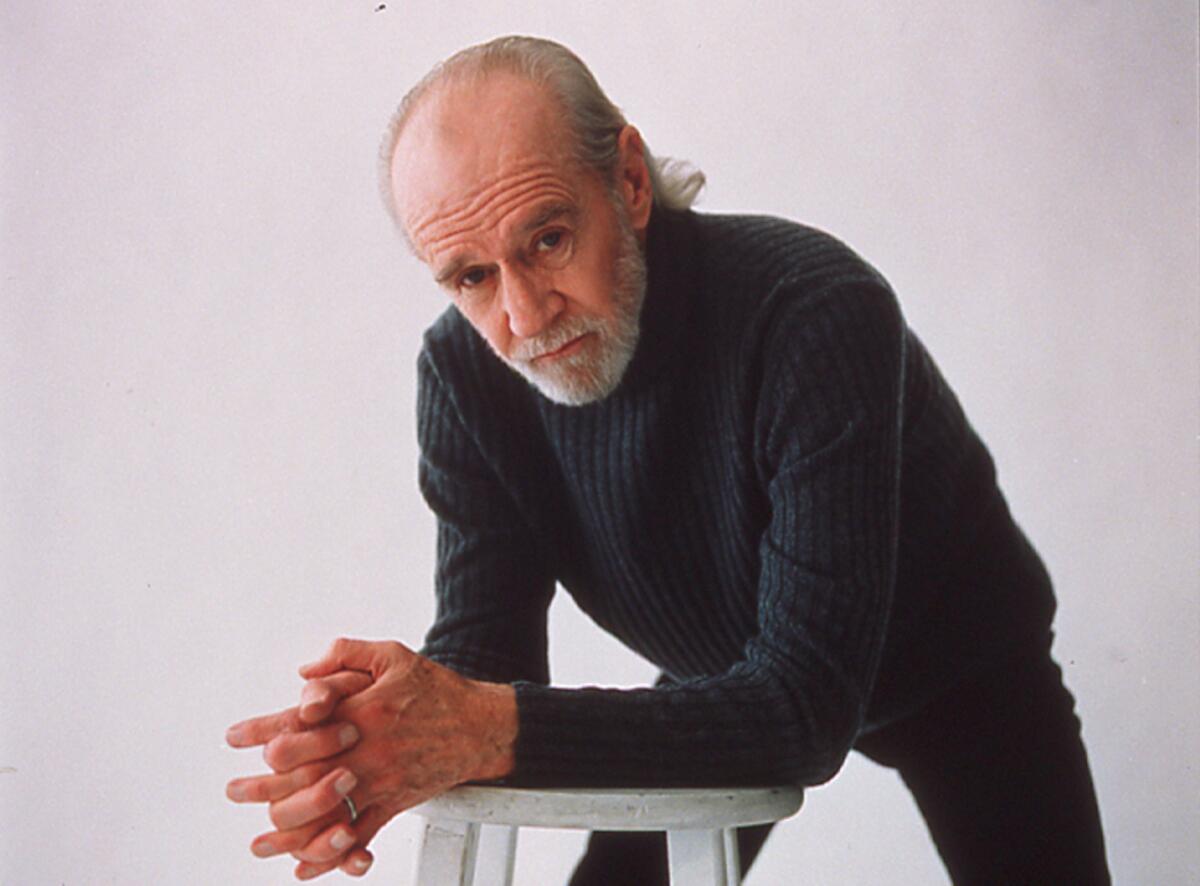

George Carlin documentary lets the comic speak to a new era

Before he became a counterculture hero by publicly invoking “The Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,” George Carlin dropped out of high school, DJed in the Air Force, joined Lenny Bruce in the back of a paddy wagon as a show of solidarity after the comic got arrested in a Chicago nightclub, lost a $250,000-a-year gig in Las Vegas for swearing onstage, took LSD at home in the presence of his wife and daughter, survived two heart attacks and consumed loads of cocaine.

Also, before his death 14 years ago at age 71, Carlin helped revolutionize stand-up comedy.

“Carlin did comedy in so many different ways,” says comedy kingpin Judd Apatow. “He did funny voices; he examined language; he did epic rants; he did characters — if you watch a lot of George Carlin, listen to his records, it is the playbook for how to be a comedian.”

Writer-director-producer Apatow, who earned a 2018 Emmy for “The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling,” teamed with Michael Bonfiglio, director of recent Jerry Seinfeld and David Letterman specials, to make “George Carlin’s American Dream.” The two-part HBO documentary, nominated for five Emmy awards, celebrates the comedian’s scathingly funny observations and examines his not-so-funny personal life through rare archival material, interviews with family members and commentary from fans — including Seinfeld, Chris Rock, Stephen Colbert, W. Kamau Bell and Jon Stewart.

Apatow, Zooming in from a film shoot in North Carolina, and Bonfiglio, speaking from his New York home, talked to The Envelope about their two-year journey into the private heart and scintillating mind of the late George Carlin.

George Carlin died in 2008. When did you get the lightbulb moment that now is the time to make a documentary about him?

Apatow: We didn’t have that lightbulb moment. Our producer Teddy [Leifer] did. But when HBO came to me and asked if Mike and I would be interested in this subject matter, it became clear in seconds that George Carlin is a much-needed voice at this particular time.

That voice comes through loud and clear at the end of the film, where you underscore this montage of current crises with one of Carlin’s uncannily prescient rants. How did that come about?

Cheer up at one of these spots for stand-up comedy in L.A.

Apatow: We put together that sequence late in our edit. Our brilliant editor Joe Beshenkovsky did the first cut and then we all jumped in for another month just on those five minutes because it was important for us to get George Carlin’s point of view out there on these big issues. He was very clearly for gun control, for freedom of choice, for separation of church and state, against financial interests controlling the media and the government and on and on.

What was the most surprising thing you learned about George Carlin that you didn’t know before making this documentary?

Apatow: I didn’t know hardly anything about his personal life. George Carlin had a similar trajectory to a lot of people in comedy in that he came from a traumatic childhood. His father abused his brother Patrick. His mom got a divorce in the ‘30s, when people didn’t do that, and ran away to protect George and his brother. He was raised by a domineering mother who felt that everything he did was a reflection on her. I love George Carlin as a comedian and I’m interested in his career, but I’m much more interested in his journey and evolution as a person.

Part of that evolution connects directly to his 36-year marriage to Brenda Carlin, whom he met at a Dayton, Ohio, nightclub in 1960. It’s ultimately a touching love story but your film also documents the turmoil.

Apatow: We put a lot of care into portraying Carlin’s relationship with his wife, Brenda Carlin. They went through a lot of turbulent times, but in the end, they got over their addictions and healed.

Michael, you interviewed Carlin’s daughter, Kelly, about those volatile family dynamics?

Bonfiglio: Kelly tells the story in the film about how the time he had a bad [acid] trip when she was a little kid and she had to calm him down with her mom. It was wonderful to get her insights because Kelly was willing to bare it all and not worry so much about protecting what people’s ideas about her father might be. That allowed for a great level of honesty.

Carlin kept his private life, including a happy second marriage to Sally Wade, offstage. In his professional life, Carlin made headlines in 1969 when he got fired from a lucrative Las Vegas gig, grew a beard and re-invented his act.

Bonfiglio: Carlin understood how to use these reliable show business techniques he’d honed over a long period of time in nightclubs and television to present this countercultural material. This wasn’t just a gimmick. It was an almost spiritual transformation that Carlin makes into really finding his voice.

Apatow: There are actually four or five phases. After he decides to “be himself” and do a more honest, somewhat political act, Carlin has some drug problems and heart attacks, so his act gets a little softer because he doesn’t want to upset himself and have another heart attack! But at some point, he sees Sam Kinison and decides, as he says in the film, “I don’t want to be breathing his dust the rest of my career.” So then Carlin goes really hard. And then there’s this final phase where he goes even harder, taking the point of view of someone who’s given up on humanity.

Some fans of Carlin’s earlier work, including Stephen Colbert, felt that final phase was just too bleak.

Apatow: A lot of people thought that final evolution was too dark, but looking back now, you watch those specials and think, “Maybe not dark enough!”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.