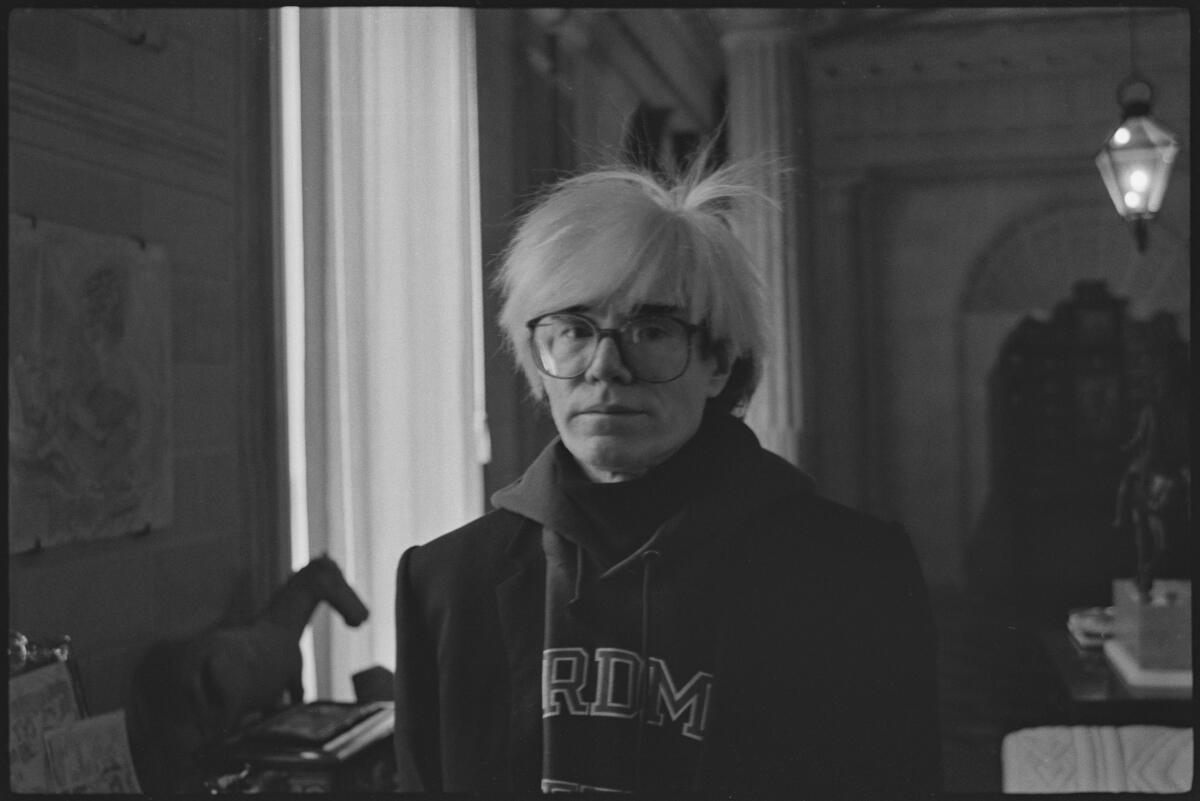

Andy Warhol gets another 15 minutes in documentary about his later years

So elemental a force in mass media that someone might reliably call him a hyperobject — like the internet, or a black hole — artist Andy Warhol has never been fully understood as a human being by a popular culture he in many ways created.

That’s something filmmaker Andrew Rossi works extensively to change in his six-part Netflix documentary series “The Andy Warhol Diaries,” executive produced by Ryan Murphy, which draws on the pop artist’s most intimate source material, the diaries he dictated daily to his amanuensis Pat Hackett between 1976 and his 1987 death.

No need to rehash Warhol’s epochal 1960s, the spinal column of such recent nonfiction faves as Todd Haynes’ “The Velvet Underground.” “But rather,” Rossi said, “understand how Andy resonates with our current moment through his personal life and through his later artwork, which has been rarely investigated.“ The filmmaker often is drawn to cultural mainstays, whether the New York Times in “Page One” or the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its annual fashion gala in “First Monday in May.”

The series received four Emmy nominations, including three for Rossi for writing, directing and as executive producer of the nominated series. Long fascinated with Warhol, it took time for Rossi to find a way into the story.

“Andy Warhol was always a hero to me and represented a queer sort of safe space as I was growing up and figuring out my sexuality,” Rossi said. His first time reading the diaries, its “morass of parties and celebrity names” didn’t connect. But when Rossi began to work on the project in 2011, he returned to those pages. “I was shocked to see these incredibly personal and vulnerable statements from Andy. ‘The Andy Warhol Diaries’ for me is a love story.”

Alice Sedgwick Wohl’s ‘As It Turns Out,’ on power duo Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick, is not a memoir but an investigation of a cultural obsession.

The series’ arc follows Warhol across his romantic relationships with Jed Johnson, a designer who lived with the artist for 12 years, and Jon Gould, the Paramount executive who tried to keep the nature of their relationship under wraps. Rossi also looks closely at Warhol’s late-career connection with the ascendant East Village art star Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Although marked by Warhol’s signature wit, the episodes are imbued with “a golden-hued melancholy,” Rossi said, a quality clued by the theme music — Nat King Cole’s ballad “Nature Boy”— and inherent in the events of Warhol’s later years, when the artist’s very public celebrity often was caught in the shadow of the silvered disco ball.

“The underbelly of that experience tied to this existential threat of HIV/AIDS,” Rossi said, “tied to his feelings that people were calling him a has-been and his peers, like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein, are selling at higher prices, tied to his heartache: His domestic partner breaks up with him and tries to take his own life twice, and then his lover Jon Gould dies of HIV/AIDS. All those things are not explicitly said in the diaries, but they are suffused in his experience.”

In addition to an array of interviews with celebrities, art curators, former associates and others, Rossi had access to a mother lode of resources from the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the artist’s hometown. He also utilized a remarkable collection of 130,000 negatives Warhol made on his snapshot cameras between 1976 and 1987, held in the Andy Warhol Photography Archive at the Stanford Libraries. “That was a revelation,” he said of the database, which was launched in 2019.

Technology also plays an unusual role in allowing the series to give uncanny voice to its subject. The use of an A.I. program to replicate Warhol’s flat, affectless speech to read the diary entries had a strangely fitting logic. “Andy made himself into a robot,” said Rossi, alluding to the mechanical Warhol, created for a 1982 production that never happened. “He always said robots don’t have feelings and wouldn’t one want to be a robot?”

The voice was a hybrid. The filmmaker worked with the company Resemble AI, using a brief segment from an interview Warhol did with the BBC, to fabricate what ultimately combined the A.I. algorithm and human voice of actor Bill Irwin. Unlike the fleeting use of A.I. to re-create late raconteur Anthony Bourdain’s voice in a few spots of Morgan Neville’s 2021 film “Roadrunner,” which caused a controversy when it was not initially disclosed, the Netflix series is upfront about the technology. But it’s also a bit clever. “The voice embodies a contradiction in a way,” Rossi said. “Andy is talking to us, but it leans into that it is a robot.”

Ultimately, of course, the material speaks for itself.

“I always viewed the diaries like ‘The Canterbury Tales,’” Rossi said. “I think there’s something about the blankness or simplicity of a lot of the diary entries that mirrors that old English style of storytelling .… They might as well be from the Middle Ages. Some of those people, you don’t know who they are, but you can feel the contours of some sort of emotional journey he’s taking with someone he saw, his assessment of the different social standing of people in a given environment.

“In cases like the Diana Ross concert” — Warhol was present for the singer’s 1983 Central Park performance, whose preemption by a lightning storm was captured on film with a biblical grandeur — “it reaches an almost transcendent, spiritual level.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.