How a sense of place and family link generations in ‘Pachinko’

Turning Min Jin Lee’s expansive historical novel “Pachinko” into an eight-hour Apple TV+ series was a daunting proposition. Lead creatives Soo Hugh, Justin Chon and Kogonada could do so only by making it their own.

The saga of a Korean family — oppressed by imperial Japan’s occupation in the early 20th century, dislocated when the tale’s matriarch, Sunja, moves to Osaka in the 1930s, and reassessed when her U.S.-educated grandson, Solomon, returns to Japan in 1989 — was restructured by showrunner Hugh as a more personal reflection of her own Korean American experience.

“‘Pachinko’ reminds me of my parents and grandparents,” Hugh (“The Terror”) tells The Envelope. “Growing up, I had so little of that kind of connection to what I read. It was as if I had suddenly seen my soul come to life.

“But it took me a while to figure out how to do it,” she says of adapting the book. “You can tell the story linearly as the novel does, and it would have been a beautiful show. But I would have missed out on saying something about my life, about the cross-generational dialogue. When I keyed into that, it felt like we were doing something that was of the moment.”

The series moves through time and space in emotionally reflective ways. Though its cast is vast, the series centers on the journeys of several key characters. Newcomer Minha Kim portrays the young heroine Sunja and South Korean national treasure and “Minari” Oscar winner Yuh-Jung Youn plays her in her 70s; Korean American Jin Ha is Solomon; and Hallyu superstar Lee Minho is Hansu, a Japan-born Korean who has a profound effect on Sunja’s life.

The Korean family epic, based on the novel by Min Jin Lee and starring ‘Minari’ Oscar winner Yuh-Jung Youn, is a lesson in how to do melodrama right.

Chon (“Gook,” “Blue Bayou”), like Kogonada an acclaimed Korean American indie filmmaker, also loved Lee’s book but considered it too unwieldy for a TV adaptation. When he read Hugh’s pilot script, though, the Orange County-raised actor-director knew she had cracked the code.

“The biggest thing is they didn’t make it linear,” Chon says. “They had different timelines so that you’re traveling parallel from the 1980s to earlier in the 1900s. That allows us to know and see that whatever teenage Sunja does is going to reverberate in the show’s present. That really helped, and also beefing up Solomon’s role in the series. Sunja’s grandson represents how the choices you make are going to have consequences or benefits for future generations. The call-and-response to that is compelling.”

So are the ways in which Chon and Kogonada composed the show. The production spent four months in various South Korea locations, some of which doubled for 1920s Yokohama and 1980s Tokyo (plans to film in Japan were curtailed by COVID). Then another four months in Vancouver, mostly for interiors. With both of their units filming simultaneously, sharing casts and sets and block shooting scenes from different episodes most days, the auteurs still managed to get their distinctive styles and obsessions onscreen. Kogonada directed Episodes 1-3 and 7, Chon did 4-6 and 8.

“The first three episodes really have to establish a sense of place because so much of this series becomes about displacement,” says Kogonada, whose films “Columbus” explored the Indiana city’s unique architecture and “After Yang” examined what makes a home. “You must feel the place that Sunja comes from and her sense of home, no matter how difficult it was. When you get to Episodes 4 on, where she’s in a new world, things get more dramatic. Justin’s films have always been about displacement, they really excel at the emotion of that.”

Chon agrees.

“Kogonada’s very disciplined, his frames are very set and thoughtful and give you the space to think and get introspective,” Chon observes. “I just like to blast people. I’m a little bit more bombastic, I like a lot of movement. I like things to feel high-impact, high-energy. And I like to really be in the mind of the characters, a lot of closeups and stuff.”

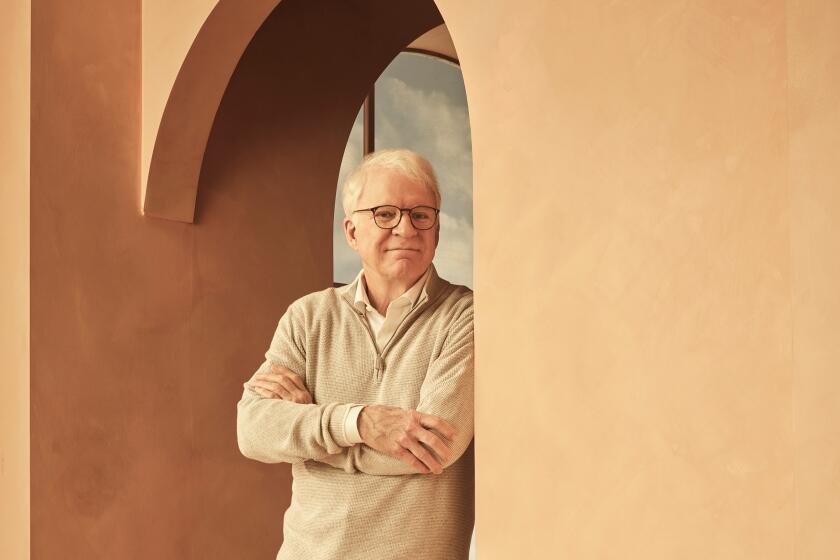

Oscar winner Yuh-Jung Youn comes to American television with the sprawling family drama “Pachinko.”

Kogonada pays homage to a hero, director Kenji Mizoguchi, with long tracking shots and sensitivity to female endurance throughout — and in Episode 7’s re-creation of 1923’s Great Kanto earthquake, applies what he calls the Japanese master’s “haunted camera,” the stately, almost funereal tracking shots used in such ghost stories as “Ugetsu.” Amid physical and cultural chaos, Chon repeatedly locates touching family interactions in spaces like a newlywed migrant couple’s cramped bedroom or an AIDS victim’s hospital ward.

“They’re just phenomenal filmmakers,” Hugh says. “The ambition was that if you take one frame from ‘Pachinko,’ it won’t feel like any other show. We want it to feel like only we could have made it in this time and place. Justin and Kogonada really embraced that thinking. And they have personal connections to the story as well, which is very important.”

“A lot of credit goes to Soo and the producers for choosing Justin and I,” Kogonada says. “We’re both really indie filmmakers, and there are a lot of veteran TV directors who would have the experience for a project like this. But I think that they were looking for distinct voices and looking to do something that didn’t feel like TV.”

Provided with resources well beyond what they’d ever had in their films, the directors valued one thing above all.

“To be honest, I really didn’t get any notes the entire shoot,” Chon says, still sounding amazed. “They just let me do my thing.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.