Bob Odenkirk doesn’t remember anything about his heart attack last summer — not the CPR, not the three defibrillator zaps that brought him back to life and nothing from the eight days he spent recuperating at Albuquerque Presbyterian Hospital. Even the week after he went home is sketchy. He vaguely recalls his wife, Naomi, and adult kids, Nate and Erin, being with him and time spent with his “Better Call Saul” co-stars (and Albuquerque roommates) Rhea Seehorn and Patrick Fabian.

But that’s it. No white light moment? I ask him. No encounters with St. Peter or a dearly departed pet?

“No,” Odenkirk answers. It’s a hot day, the Santa Ana winds are blowing and we’re sitting indoors at a poolside restaurant at the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, sipping mojitos, far removed from the day Odenkirk collapsed on the set of “Better Call Saul.” I express a little disappointment that Odenkirk cannot offer me reassurance about an afterlife.

“You’re disappointed? I’m disappointed,” Odenkirk says. “I wanted to have that tale to tell. I wanted to tell you which of my relatives was first in line to greet me. I wanted to see Abraham Lincoln playing chess with Elvis Presley and get in on that game. I think Lincoln’s probably going to win. But only after Presley throws the board across the room and knocks Lincoln’s hat off.”

Odenkirk, 59, chuckles. But just a little. He thinks about his near-death experience often and, yes, on one level, he feels a bit cheated. If his heart is going to stop and he’s going to turn bluish-gray because he isn’t breathing and if they have to put the paddles on him to jump-start his pulse, he would have liked just one grand, existential moment of awareness and maybe a couple answers about what’s next. Instead, he just got a big blank space.

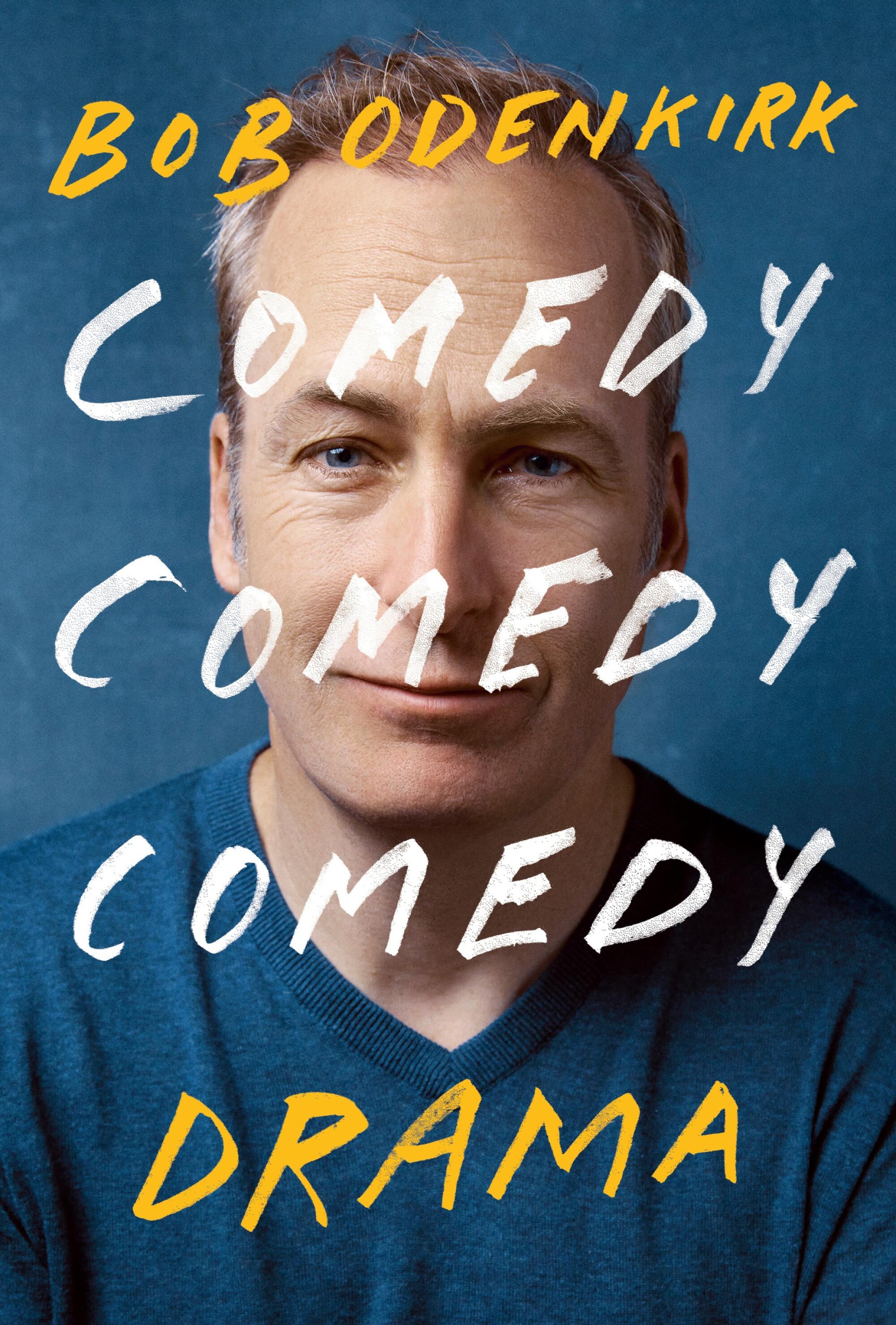

Of course, that’s not all he got. Odenkirk also received a monumental outpouring of love from complete strangers on social media — platforms he calls “this horrible thing that has degraded us” — and that he remembers. Odenkirk still can’t wrap his head around the kindness directed his way. He’s not a warm-and-fuzzy guy. His comedy career — Chicago club stages, writing for “Saturday Night Live,” creating and performing “Mr. Show” with David Cross, all chronicled in his excellent memoir “Comedy Comedy Comedy Drama” — has been predicated on the idea that the best humor comes from a place of anger. And that people are stupid. And that life is dumb.

And sure, audiences do treasure Saul Goodman, the fast-talking attorney who provided “Breaking Bad” with moments of comic relief and turned into a cautionary tale and tragic antihero on “Better Call Saul,” now in its final run of episodes.

“But Saul’s not a good guy,” Odenkirk says. “He’s very selfish. So I don’t think it’s that.”

This ignites a good-natured debate — it won’t be our last — about how “Better Call Saul” made us feel something deeper about Odenkirk’s character, introduced as Jimmy McGill, a man of many talents, one of which is scamming. He’s a scamp looking for approval, foolishly, it turns out, from his older brother, memorably played by Michael McKean. And when that relationship turns sour (to put it mildly), it fuels frustrations and resentments that Jimmy can’t leave behind.

Anyway, we feel something for the guy — and for the actor who has played him for a decade.

“I’ll allow that,” Odenkirk says. “But I don’t think it explains that outpouring of warmth. I think that came from COVID, which freaked everyone out and led to this feeling of ‘Can we just not have more bad things happen to us for a little while?’ And then, you know, I’m not a movie star. I’m just a guy who acts and works hard. I think people see me and think, ‘If I was an actor and had a great bit of luck, I’d be like him. He’s not a flashy guy. He’s not even particularly gifted. He just shows up and goes to work.’ People can relate to that. And maybe that provoked a certain amount of empathy.”

Odenkirk isn’t pushing false humility. He likes to analyze things — his memoir could be used as a textbook for understanding sketch comedy — and this is his genuine take on why the world joined hands last summer and wished him well. I think he’s wrong, but his reasoning is completely in character.

“Bob, being who he is, is always grappling with the subtext going through his head,” says his co-star and friend Seehorn. “Like, when he was writing the book, he had to wrap his mind around, ‘Well, who am I to be writing a bio?’ And I would tell him time and time again that he has this breadth of work and expertise in comedy and a million funny stories and he’s a great writer and has taken risks and tried things and they haven’t always worked out, but he keeps trying. That’s interesting. Who wouldn’t want to read about that?” She pauses. “It took some convincing.”

The book, which Odenkirk wrote over the course of a few years (“Oh, my gosh, the cursing you would hear from upstairs,” roommate Seehorn says, laughing. “I just thought he was going to light so many reams of paper on fire on a weekly basis”), ended up containing a fair amount of advice, along the lines of “if I can do it, so can you.” Odenkirk doesn’t consider himself some wise old sage (“old, maybe,” he says), but he does think people can learn things over the course of time and even change. That belief has been at the heart of the many arguments he’s had over the years with “Saul” creators Peter Gould and Vince Gilligan.

“My pitch to them is always: Sometimes people learn the right lessons from challenges and trauma,” Odenkirk says.

The first five seasons of the series have opened with a flash-forward of Saul, now going by the alias of Gene Takavic, living in Omaha, Neb., managing a shopping center Cinnabon and living a bleak, empty, low-key life. The last time we see Gene, he believes he’s been made and needs to change his identity and disappear again. And then he seems to see something and changes his mind.

“He’s looking back on his whole life and asking himself, ‘Do I react the way that my instinct tells me, the same instinct that has landed me in a f— mall in Omaha, making cinnamon rolls? Do I keep following that gut?’ He’s still Jimmy McGill. He’s still Saul Goodman. I promise you that. But in his growth, he’s asking himself, ‘Really? Is this all worth it?’ And you see in that moment that he can’t hold that s— in any longer. He needs to be himself.”

“I can’t tell you where he ends up, but it’s not like he has some revelation of humanity.”

— Bob Odenkirk on Saul

We’ve spent the good part of an hour dancing around what’s to come in the show’s remaining episodes. Odenkirk can’t tell me, and I don’t want to know. But without getting into specifics, it would seem that Odenkirk may have finally won his long-standing argument with the series’ writers, allowing Saul to step past his resentments.

“You know, I’ve had my bitterness and frustrations, but whenever I see that at play, especially in a choice I’m going to make, I say, ‘That’s bull—. That is not a way to move forward,’” Odenkirk says. “And with Saul, I’ve always told Peter and Vince that sometimes people learn the right lessons and not the most selfish, resentful lesson from a bad thing that’s happened to them. They become bigger and more gracious and not smaller and ground-down.

“This is not a spoiler, what I’m saying here,” Odenkirk adds. “It’s weird, because it sounds like maybe I’m pitching that Saul becomes this goodhearted, generous, caring person. I can’t tell you where he ends up, but it’s not like he has some revelation of humanity. I think he gets to …” Odenkirk pauses. “I think I’ve said all I can say. But I like where his journey ends. And I think you’ll like it too.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.