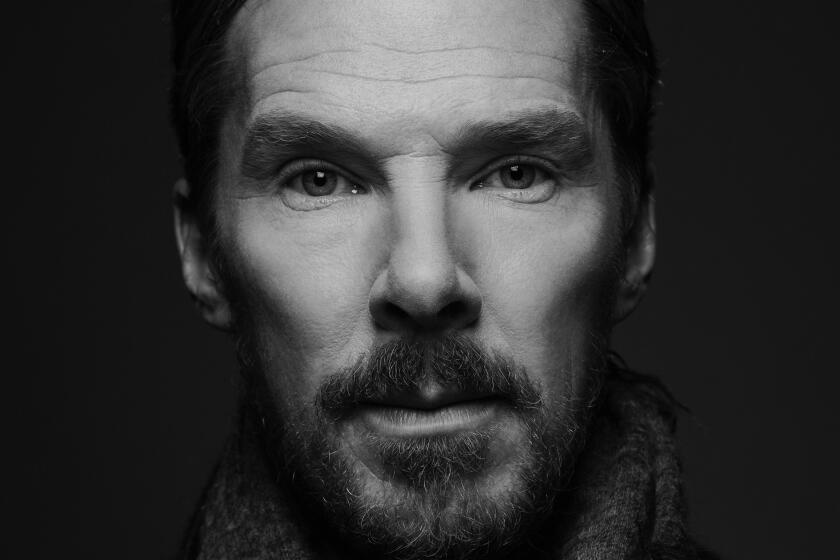

Production designer Grant Major and set decorator Amber Richards turned their native New Zealand into 1925 Montana for Jane Campion’s “The Power of the Dog.” Exteriors built in the South Island’s remote Ida Valley and interiors created on converted warehouse soundstages in Auckland exude weathered, western authenticity. Inspirations included Evelyn Cameron’s frontier photographs, Theodore Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill estate, 1925 mail order catalogs and Thomas Savage’s 1967 source novel about closeted, overcompensating rancher Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch), his passive brother George (Jesse Plemons), the latter’s delicate bride Rose (Kirsten Dunst) and her deceptively formidable son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee).

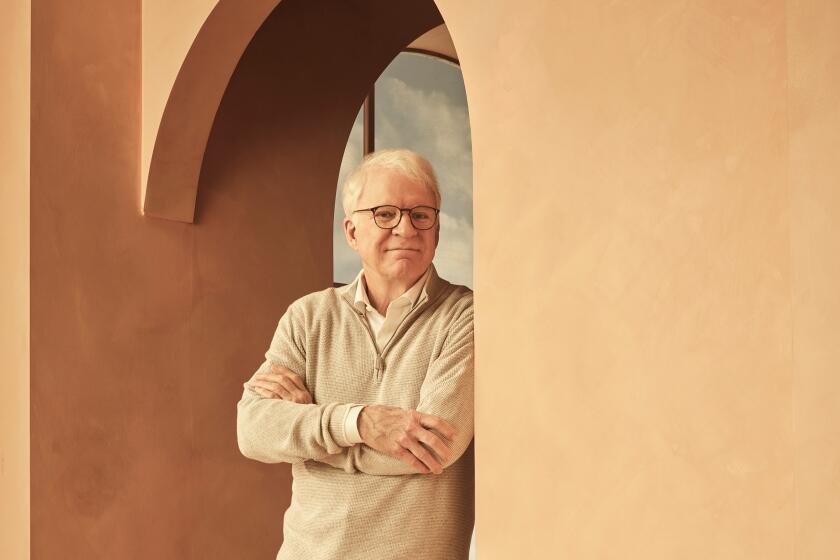

Major, who hadn’t seen Campion since he started designing films with her 1990 “An Angel at My Table,” is nominated for his fifth Oscar (the others were massive Peter Jackson fantasies; Major won for “Lord of the Rings: Return of the King”). Richards, up for her first Academy Award, came to “Power” from a set dressing gig on “Avatar 2.”

Maybe ease up on your hatred of Phil Burbank just a little, the actor asks. There are things about the man that should be celebrated.

“The transition was quite strange, I have to say,” she said in an understatement while, like her frequent colleague Major, expressing the joy of crafting practical environments. They spoke with The Envelope on a conference call from their Auckland homes.

The location you chose for the Burbank ranch, Home Hill Farm, was so isolated the production had to make its own access roads. Why go there?

Major: It really offered the best sense of place. It had a beautiful mountain range to the north, which runs in an east-west direction so we get the side light in the morning and the afternoon. There were hardly any trees on the property, so it had this sort of barrenness to it, which was in line with the Evelyn Cameron photographs’ look. Sort of a reductionist view of the buildings without very much else around them.

How much of a build was that Victorian/proto-Craftsman mansion facade?

Major: The valley was particularly windy. We would not have been able to stand up a three-sided facade without it blowing over, so we had to build four walls for that. We couldn’t afford to build the very top roofs, so that was put in afterward by VFX. The house was largely a facade except for inside the front door and some of the windows, and also what we called the cowboys’ dining room at the very back. That’s where the camera tracks past windows and we see Phil Burbank for the first time.

From the brothers’ twin bedroom to the dark parlor with its heavy furniture and taxidermy, the interiors reflect the men’s stunted, lonely psyches.

Amber Richards: We were aiming to suggest that the boys hadn’t really changed much since the parents left, but the house had emptied out a bit. On the whole, when Rose arrives it is cold and unfriendly and Phil didn’t really like things moved. It was a little bit bachelor, not a place for a woman.

The barn you put up, where Phil has his iconic shrine to his lost mentor and love Bronco Henry, accommodated both interiors and exteriors.

Major: The shrine was central to the dressing on the inside of the barn, which was very much a Phil environment. It was always going to be about the saddle in particular. I can’t remember if the plaque with “Bronco Henry” was in the script or not, but somehow we did end up designing a plaque and a little shelf with spurs. Then I added a small lamp to go above it, so that we could appreciate it in the darkness of the barn.

You had to find everything from century-old pianos to Peter’s cane hula hoop. You filled a 40-foot shipping container with stuff from Hollywood prop houses!

Richards: I mean, it was a buying dream, this job. Within New Zealand, we were able to tap into lots of amazing collectors and, especially down south, there were small towns with old shops full of things. But there was a different style of furniture of the time that I realized we wouldn’t be able to source locally.

I came over for four-and-a-half days, and I was blown away by the support and generosity of everyone. Universal specifically bought a stove for me, which ended up in the ranch kitchen. Antiquarian Traders has this dark warehouse near Downtown L.A. with all these incredible chandeliers and pieces of furniture, on a scale which you’d never see in New Zealand.

We used every single piece that we brought over; it was really worthwhile.

The production manufactured its own wallpaper, linoleum and, I hope, bull testicles?

Richards: They were definitely synthetic! [laughs] Made out of silicone.

Is it OK if we don’t see the dog image in the mountains? It took me a couple tries.

Major: It’s interesting, isn’t it? The name for it is pareidolia, when you see faces and animals and what have you in the landscape. Some people see it and some people don’t.

It’s a CGI effect, but I did produce a lot of drawings in the early days for the forms of the landscape looking like a dog, or with a lighting or shadow effect. We ended up with a design by Jay Hawkins, the visual effects supervisor. Jane loved the look of it.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.