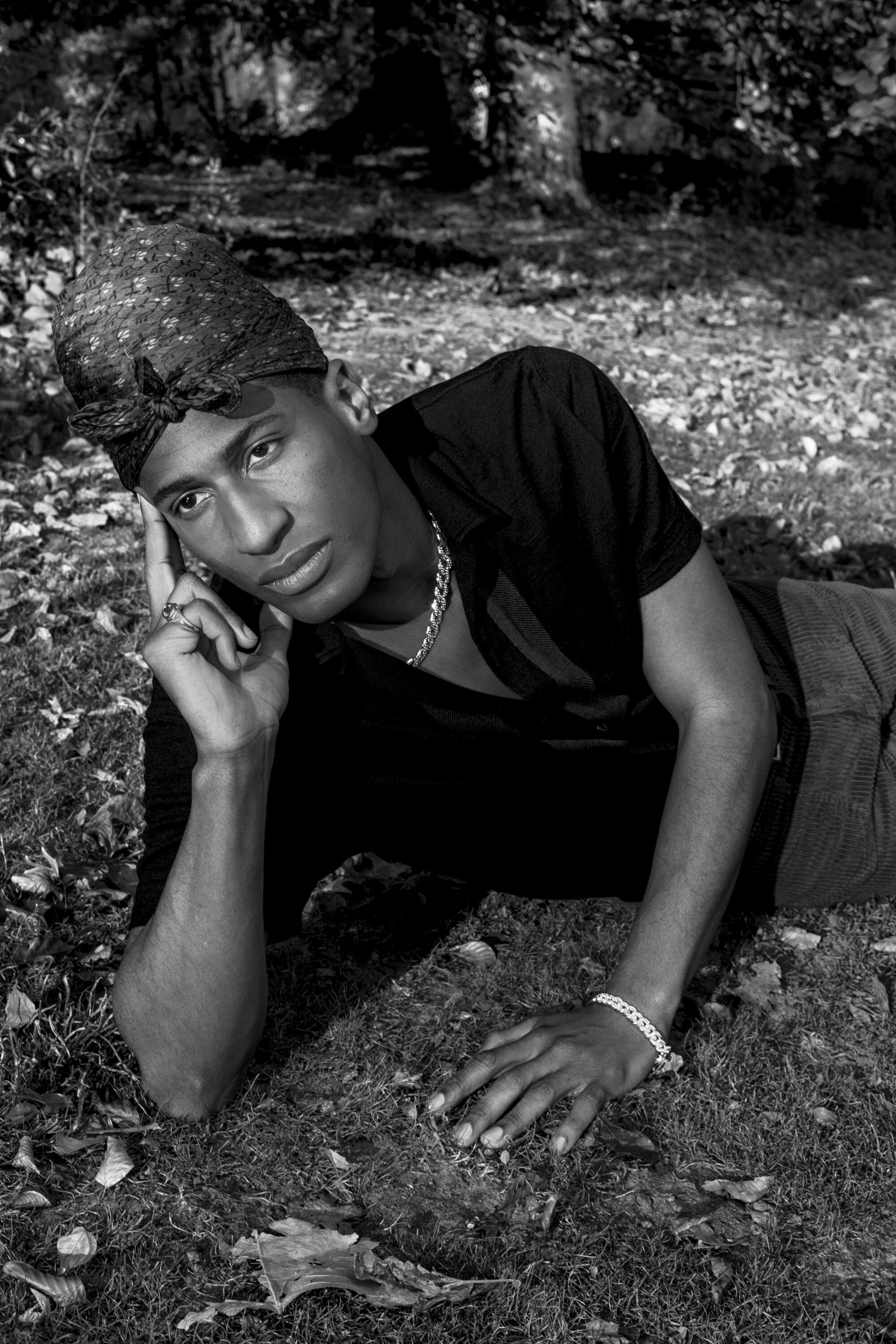

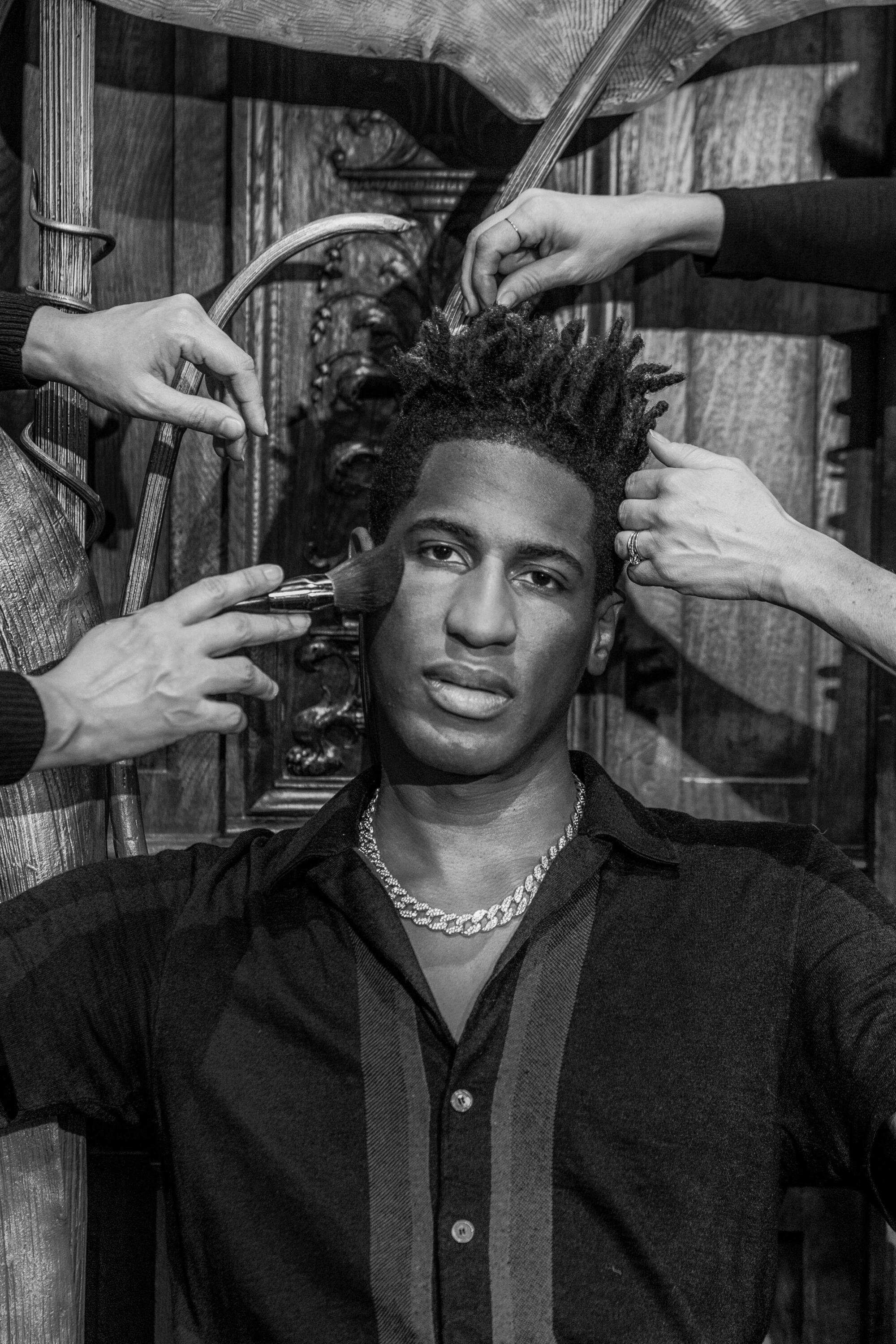

The most important day of Jon Batiste’s career got off to a bumpy start.

On Nov. 23, the day Grammy nominations were announced, Batiste was part of the morning livestream, and he had a challenging assignment: pronouncing the names of the nominees in five Latin or Mexican categories.

Batiste, who is not a native Spanish speaker, was nervous about navigating the tildes and the rolling Rs. “I was focused on being a good presenter and on carefully and respectfully trying to pronounce the names of the Latin artists,” he recalls with a laugh over Zoom. Some of the names were familiar to him, and with the rest, he moved cautiously through each syllable.

On Twitter, people were clowning the 35-year-old singer, piano player and bandleader for his slow cadence. “Jon Batiste fighting for his life,” one wag tweeted. And a TV executive added, “OK give Jon Batiste a Grammy for having to pronounce all of those names.” As it turned out, Batiste didn’t need any help.

Batiste completed his bilingual navigations, and then the American roots category was announced. Batiste had been nominated in that category before, in 2018, so he paid attention and heard his name announced for roots performance and roots song, both for his 2021 album “We Are.” “After that,” he recalls, “I couldn’t hear anything.”

There was a lot of noise in his New York apartment, because it was crowded with people, including his music collaborator Ryan Lynn; his longtime girlfriend, Swiss Tunisian writer and activist Suleika Jaouad; and his parents, sister and nephews, who flew up north because Batiste was riding on the Louisiana float in the Thanksgiving parade two days later. He got a couple more nominations, then a few more, then even more. “Every time my name was mentioned, it was pandemonium. It felt surreal after a while.”

By the time the Grammys broadcast signed off, Batiste had been nominated 11 times (a tally exceeded only twice, by Michael Jackson in 1984 and Babyface in 1997), including for album of the year and record of the year. But it wasn’t just the volume of nominations that was extraordinary, it was also the range. In addition to American roots, Batiste was nominated in R&B, jazz, score, video and classical categories.

Although he’s on network TV as the musical director of “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” and he won an Academy Award this year as a composer for the Disney-Pixar animated film “Soul,” Batiste is someone who’s known more to cognoscenti than to the masses. In the tradition of the “Who is Bonny Bear?” question that circulated widely in 2012, after the little-known Bon Iver won a best new artist award at the Grammys, the dominant question on social media on Nov. 23 was “WTF is Jon Batiste?”

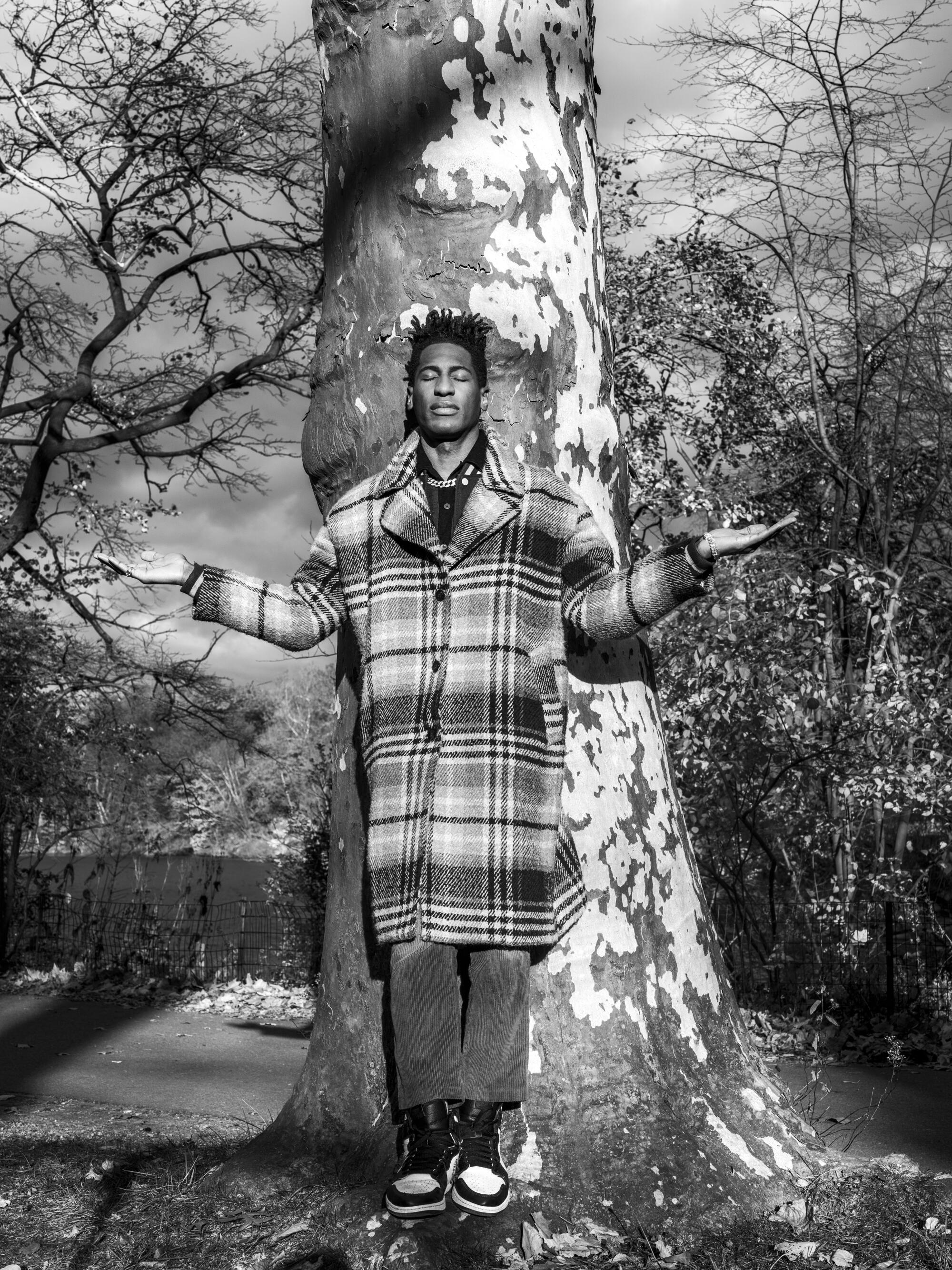

Fortunately, Batiste is adept at explaining WTF he is, analyzing what his success means and explaining what he wants to accomplish. He emphasizes two interrelated biographical details: He’s from a music family, and he’s from New Orleans.

“In New Orleans, music is part of the fabric of everyday life,” he says. “It’s our daily bread.” And, he points out, his hometown harbors a wild array of musical styles, partly due to its importance as a port city: the Spanish, French and British all passed through, as did the African and Caribbean diasporas, and West Africans from several countries arrived via slave ships.

“There’s an amalgamation of culture that’s rooted in community, and even foods, dances or social functions that go with that music. Everybody plays music because that’s the culture. The guy people buy weed from in high school plays the trumpet.”

His father, Michael Batiste, is a bassist who has performed with greats like Jackie Wilson and David Ruffin. Michael is also a co-founder of the long-running Batiste Family Band, which at one point, according to the band’s website, included 23 family members. Jon’s cousins include the late Alvin Batiste, an accomplished jazz clarinetist, and drummer Russell Batiste Jr. of the Funky Meters, one of New Orleans’ preeminent bands.

At age 8, Jon began playing drums in the family band, sometimes in front of thousands of people. When he was 11, at the suggestion of his mother, he started playing piano. Two years later, he was leading his own bands and starting to form ideas about making music that acknowledges and pays respect to genres but isn’t limited by them.

‘Colbert’ bandleader Jon Batiste leads the field with 11 nominations; Tony Bennett, Olivia Rodrigo, Doja Cat, Justin Bieber and H.E.R. will vie for top prizes.

While he was growing up in a New Orleans suburb, Batiste saw relatives deal with shady club owners and predatory music publishers. “I was an early student of the business, watching my dad and family, seeing how to create an environment where people want to come to your gigs, how to have a band that sounds like you and not everybody else. I understood the ecosystem of leading a band. When I went to New York, I applied all that to a way bigger playground.”

By age 17, Batiste had graduated high school and enrolled at the Juilliard School, a performing arts college in New York, where he eventually got bachelor’s and master’s degrees in jazz studies. He resolved to keep control of his music while he was still expanding and refining it.

“Major labels began offering me record deals when I was 18 and 19, and I turned all of it down. I wanted to do my own independent, circuitous route.” One of his independently released albums, 2013’s “Social Music,” crested at No. 1 on the Billboard jazz album chart. He was invited to appear on “The Colbert Report” and dazzled host Stephen Colbert by leading members of the audience out of their seats and into the streets, where they sang and danced. When “The Late Show With Stephen Colbert” debuted on CBS in September 2015, Batiste was the bandleader and second banana.

This brought an end to his independent, wayfaring phase. “Because of the TV show, I wasn’t gonna be able to tour nearly as much as I had, so I figured I may as well sign a record deal.” His first album on the Verve label was “Hollywood Africans,” a solo voice-and-piano LP he’d made with producer T Bone Burnett, whom Batiste met at a birthday party for U2 singer Bono, if you need a concrete sign that he was nearing the big time.

Batiste thinks of “We Are” as his first proper studio album, partly because it was the first time he had a budget that didn’t come out of his own pocket.

“Jon did it himself,” says star guitarist Robert Randolph, who played on “We Are.” “He produced and wrote the music. He’s the guy in charge, and it’s his vision.”

“We Are” was also the first time Batiste understood and could articulate his worldview, an idealistic and universal humanism in which music unites people but also acknowledges the specific struggle Black people face.

He participated in Black Lives Matter marches, voter registration rallies and protests after the slayings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery. “Whenever I do that kind of stuff, it makes me understand what my purpose is out here. I have a platform already, but I have to build the platform too. If people see you from afar, they don’t feel you, they don’t feel your vibrations and see you out there putting your life on the line in the first wave of the pandemic with police next to you, scowling at you —”

Batiste, who’s grown increasingly impassioned, stops short and laughs. “I don’t mean to preach at you, brother.” He steadies himself and continues. “We have to be with the people, otherwise it’s just empty words, empty notes. People have to feel that you really mean it, that it’s heartfelt.”

The Pakistan-raised, Brooklyn-based artist, who sings mostly in Urdu, received two Grammys nominations, including best new artist.

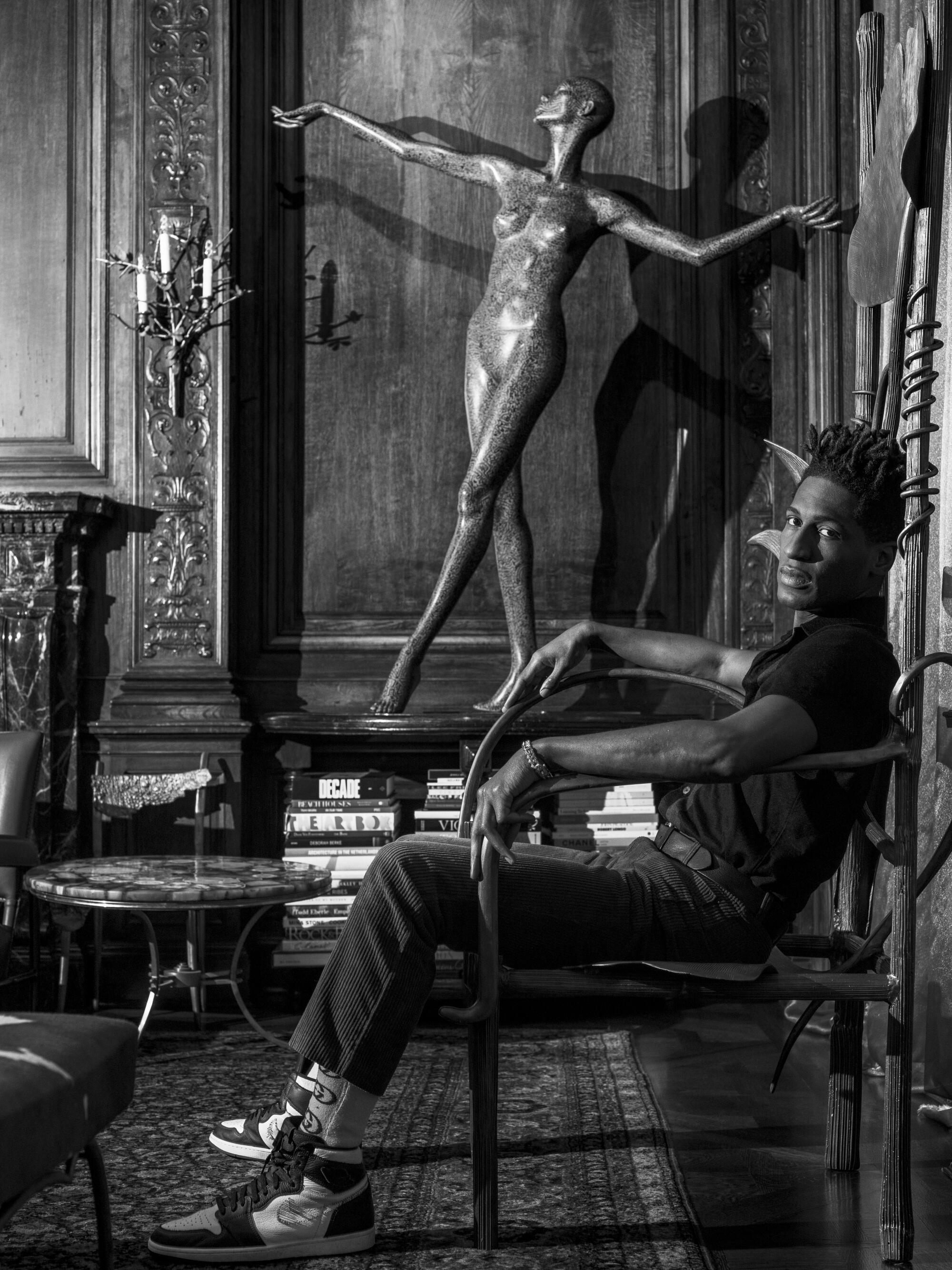

There’s nothing distant or ironic about Batiste’s music. His unconstrained avidness is a big part of what elevates “Soul,” one of the best-reviewed movies of the last few years, which centers on Pixar’s first Black protagonist, jazz pianist Joe Gardner.

“‘Soul’ is a love letter to jazz. How do we present the spirit and ethos of jazz without whitewashing it? I worked on it for 2½ years, not only as a composer but as a consultant. I was obsessed with being as authentic as possible.”

His mix of virtuosity, sincerity and positivity is a big part of what made Batiste catnip for Grammy voters. He’s socially conscious but not “radical,” accessible but not tawdry and respectful toward musical traditions. “It’s great to see him become popular,” says Randolph, “but everybody in the world of musicians already knew he’s great.”

Batiste puts a lot of responsibility on his own shoulders: to represent his family as well as his hometown, to unite listeners across boundaries, and to describe Black struggle without succumbing to despair. I asked why it was important to him to embrace such a substantial challenge.

“There’s been a void in our culture for a while. We look at music as an opportunity for upside. But beyond any financial gain or level of scaling, music is sacred stuff, man. And I feel almost called to bring it to people in these hard times. If I don’t, who will?”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.