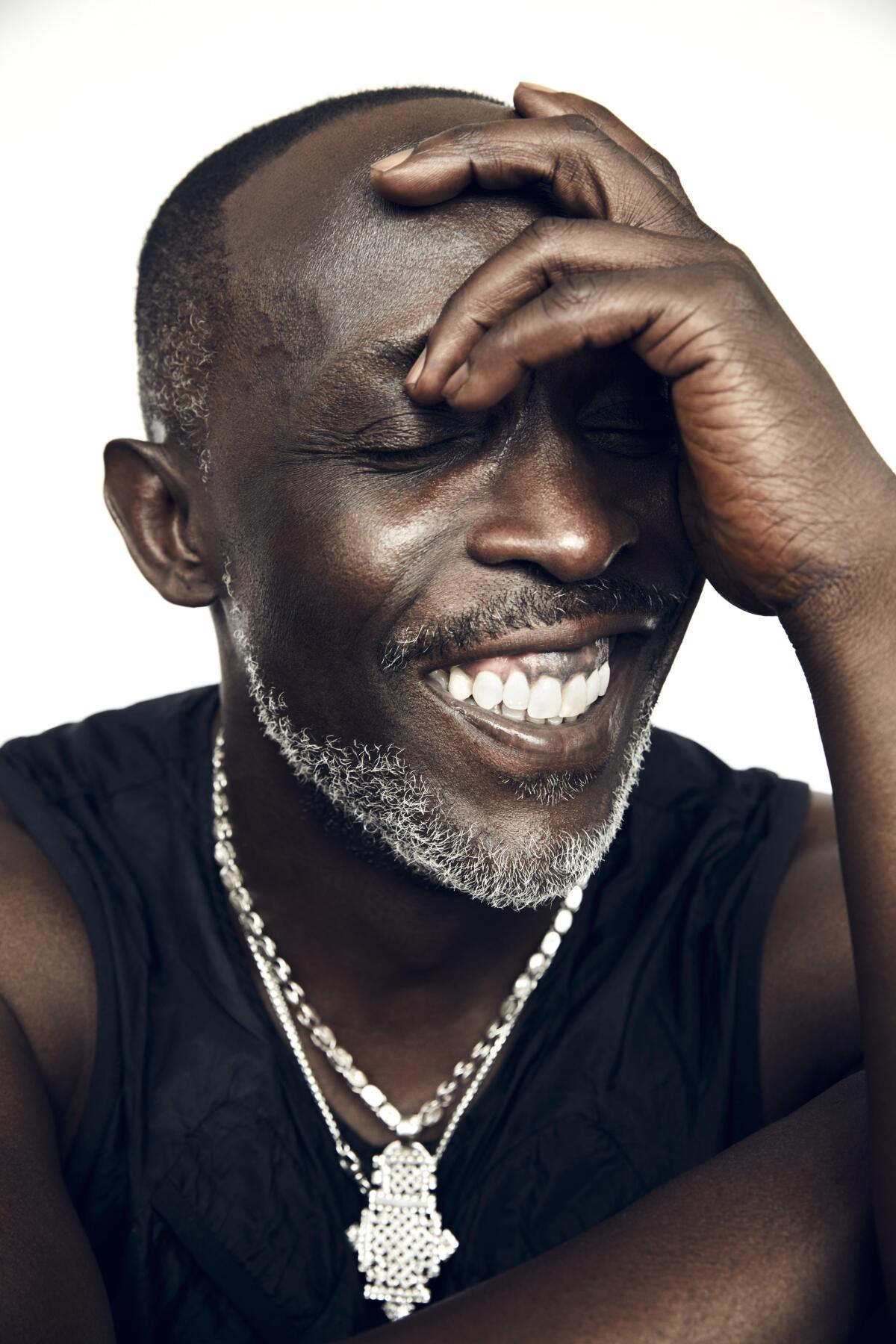

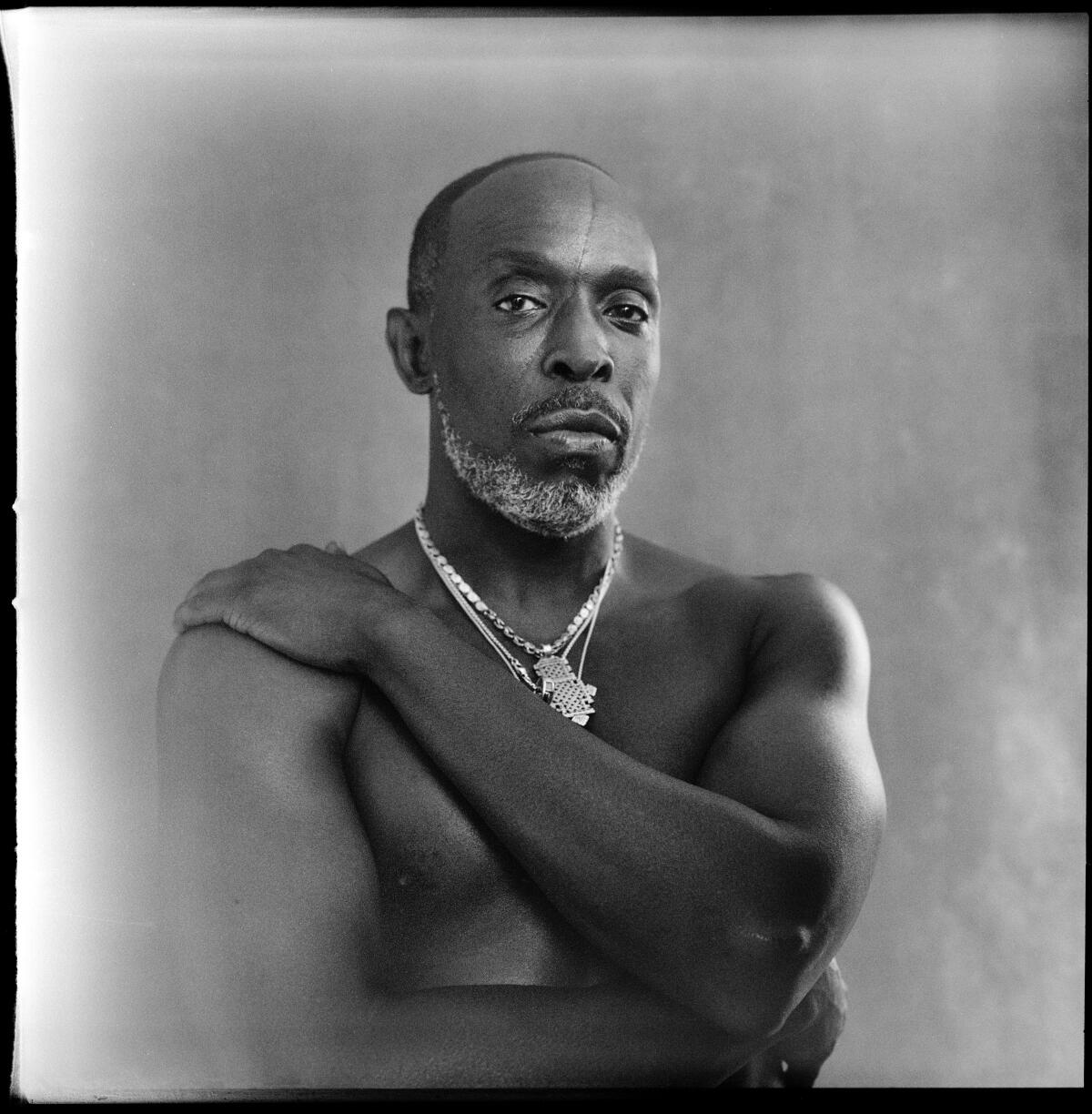

How Michael K. Williams of ‘Lovecraft Country’ came to understand his brutal character

Montrose Freeman is not easy to like for the first few episodes of “Lovecraft Country.”

“At face value, Montrose is just a miserable drunk. Really just mean to his son,” says his portrayer, Emmy nominee Michael K. Williams. “I subscribe to the narrative that ‘Hurt people hurt people.’ I try my best to look at the ‘Whys’ and not take things personal. Why is he so brutal to his son? What’s up with all the harsh beatings Atticus had to endure in his childhood from his father? When I got to Episode 9, I fully understood it.”

In that penultimate installment of the sci-fi/horror series, characters travel through time, three decades back from 1950s Chicago, to the Tulsa Massacre of 1921. There, we see Montrose’s very personal experience of that nightmare: It wasn’t just the general violence against his community that traumatized the then-young man; it was the pattern of beatings at his own father’s hands and the racist murder of the first man with whom he was likely in love.

“It was, in a weird way, out of love,” Williams says of Montrose’s brutality toward Atticus. “He was trying to protect Atticus and toughen him up so that the evils of the world would not affect his son the way they did him.”

Williams received his fifth Emmy nomination for his supporting role alongside Atticus (Jonathan Majors, also nominated). It may surprise some to learn the veteran actor has yet to win, particularly considering his iconic work in “The Wire” as Omar Little (whose super fans include former President Obama). When asked about the nomination, though, he talks instead about the other 17 nods the show received, especially for the writing staff.

“I was very, very happy to see the writers get their just due. The show was in the works for three years, being written and rewritten and rewritten. Of course, Jonathan and Jurnee [Smollett, nominated for lead actress] — but I was very happy Aunjanue [Ellis, nominated for supporting actress] got her flowers.”

Emma Corrin, Hugh Grant, Ethan Hawke, Anthony Mackie, Elisabeth Moss and Jurnee Smollett take us behind the scenes to talk narcissists, grandparents and delivering meaningful work.

Surprisingly, the actor says he wasn’t simply offered the role of the troubled father; “I had to campaign for it,” he says. “My manager even wrote a letter to the producers and the writers, letting them know how much I wanted this role.”

Montrose is a complicated guy. For all his bullet-headed machismo, he turns out to be in a down-low gay relationship.

“I don’t label Montrose’s sexual identity,” Williams says. “I don’t believe he knows what he is because he was living by these standards that were put on him for so long. I believe he’s searching.

“Montrose was given a book of stereotypes as to what it means to be a man, especially a Black man, in America. Vulnerability, softness; those are not celebrated in the community. Your experimental sexual experiences; none of these things are celebrated in the ‘hood, in the community Montrose came from, or that I come from, for that matter,” says the East Flatbush, Brooklyn native.

Williams started as a background dancer, performing with the likes of George Michael and Madonna. What he has translated from that to acting is not a physical approach to character, but a musical one.

An acting coach once told him to keep journals but Williams says, “I am frightened of keeping journals because I feel that the minute I start putting all the juicy stuff on the page, I’m gonna mess around and lose it. So my playlists are my journals. That’s how I get to the emotion I need, to breathe life into the character.”

His playlist for Montrose might not be what you’d expect — he doesn’t mention much period music.

“There was one song by Prince called ‘Father’s Song’; I used that a lot for the scenes between Jonathan and I. I listened to a lot of Gil Scott-Heron to get through to Montrose. There was some Miles Davis.”

Williams wasn’t going for atmosphere, but for the meaning and feeling of the songs; they were more of a soundtrack to Montrose’s soul than to “Lovecraft Country.” By the way, he’s a man of deep cuts: That Prince track he mentions is the instrumental played by Clarence Williams III as Prince’s father in “Purple Rain” that ended up as the solo in the song “Computer Blue.”

Williams also cites something another character said that helped him understand Montrose.

“Montrose’s brother George [Courtney B. Vance, also nominated] explains to Atticus how Montrose took the brunt of the beatings; he was smaller,” Williams recalls. “Their father [tried] to beat the softness out of him — his version of what a man should look like. George was trying to let Atticus know, no matter what, his father [Montrose] loves him. That was the first time I was like, ‘Oh. OK, I get it.’ ”

Williams expresses disappointment over the acclaimed show’s cancellation, saying he would have wanted to see “a second season. I would like to see four more seasons of ‘Lovecraft Country’.’ It did exactly what it came to do, it sparked the narrative.”

The show’s impact was likely deepened by its release during the 2020 Summer of Discontent roiled not just by the pandemic but Black Lives Matter protests as well. In the guise of horror pinging off the works of author — and virulent racist — H.P. Lovecraft, it made its supernatural creatures second in monstrousness to its Jim Crow-era humans.

“The horror genre is American classical storytelling. We’ve been telling horror stories since the beginning of Hollywood, and the only time you see people of color, we’re just the easy prey. It’s never about our relationship to what is horrifying. The Black person always dies within the first 10 minutes,” he says, agreeing with co-star Smollett’s one-time comment that “as a Black artist you can be a fan of horror but horror hasn’t always been a fan of us.”

In “Lovecraft Country,” says Williams, “The monster was the racism, the way Black people were treated in America at that time.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.