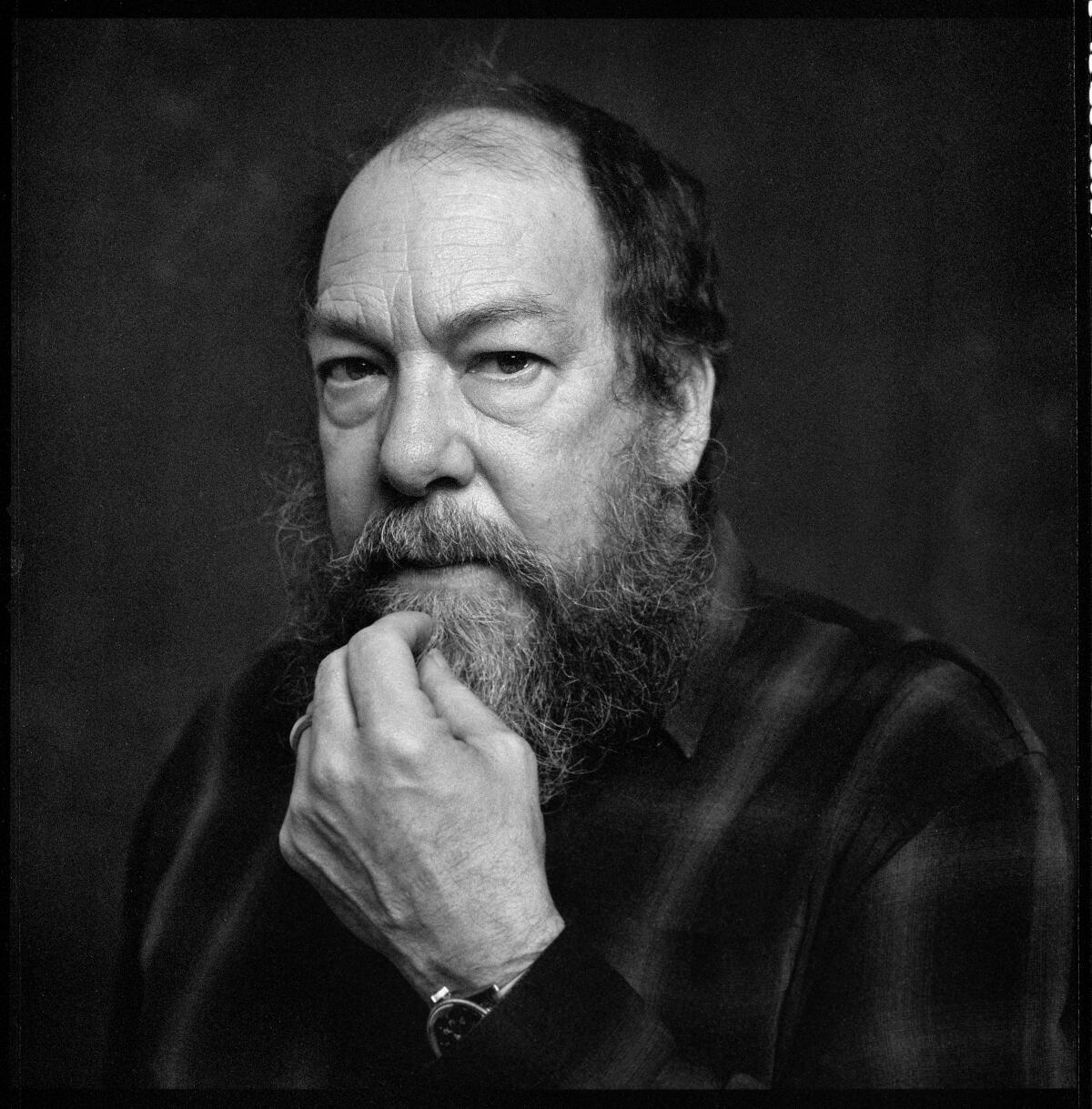

SAG nominee Bill Camp makes an impact, even in the short parts as in ‘Queen’s Gambit’

Amid all the (deserved) hoopla for Netflix’s “The Queens Gambit,” there’s one character who is often overlooked: Mr. Shaibel, the janitor who sparks the chess obsession in our young heroine. But Bill Camp’s performance — understated, taciturn and, in the end, generous — is as critical as any of the leads. That’s part of Camp’s talent: No matter where the Massachusetts native turns up — including “News of the World,” filmed with wife Elizabeth Marvel, and HBO’s “The Outsider” — he makes his contribution, whatever size, essential. Armed with a SAG nomination for his “Gambit” role, Camp dialed in from lockdown in Vermont to talk with The Envelope about his own Mr. Shaibel, overcoming his competitiveness — and bribing his son.

How much did it surprise you that “Queen’s Gambit” became such a zeitgeist hit during the pandemic?

Certainly when we made it, and I’m sure [creator] Scott [Frank] and the team, nobody had an idea what the world was going to be like a year later from when we shot it. We expected the world to be different. But it’s not a surprise, because it’s Scott Frank. He’s brilliant.

Do you play chess?

I know how to play chess, since I was in the third grade. I’m a competitive person, I have to admit. I work on my competitiveness — but I only compete in hockey.

Did you have a Mr. Shaibel in your life to teach and inspire you?

There was a group of about four or five us [who played chess], and we were taught by a gentleman who subsequently became our fourth-grade teacher, Mr. Denault. We were in a small town, Groton, Mass., in the 1970s, and he started the Groton Children’s Theater. He was the first guy who ever directed me in anything. I did three or four things with him before I went on to high school. And I keep thinking about the influence that guy had on my life. He was whip-smart and really inspiring in a passionate way to us.

Have you ever told him how much of an effect he had on you?

I must. He’s really been on my mind. My mom would know [where to find him], because she ran the school library. She’s in touch with some of those people who’ve stayed around.

So it’s fair to say he lit the spark in you for acting?

Absolutely. But who knows? I had an instinct. My sister and I used to perform Beatles songs, and my two sisters would put on musicals with their friends in the neighborhood. But if it hadn’t been for him opening the door and presenting an arena for me to be in, I may never have done that.

You’re what’s classified as a character actor today. I feel like that’s a way to get some really terrific roles. But it’s bred in us in this country that if you’re not No. 1 on the call sheet — literally or metaphorically — you haven’t “made it.” What’s your theory on that?

That whole concept was nurtured when I was at Juilliard, the perception that one has to be No. 1. They cast people who they thought would be matinee idols when they got out of school. And it’s a precondition of the culture we live in. And it gets complicated, because it’s how one identifies oneself. Right? Brian Cox said something I think is accurate, “There are short parts and long parts. You can make as much impact on a short part as you can with a long part, if you do your job right.”

About 20 years ago you consciously stepped away from acting. What was that about?

Part of it was that I was too competitive. I was too driven by the idea: “Why isn’t this happening?” My friend was like, “Why don’t you just stop for a while?” I didn’t have the courage to, because there’s this notion that’s like, “Everyone’s going to forget about you. And nobody really knows you anyway. You’re going to have to start all over again.” All of that fear-based system stuff.

You took up work as a landscaper, a cook and a mechanic during your break. Was that refreshing?

I loved it. I was getting it wrong most of the time, but that was OK. I was forgiving myself for those sorts of things, because acting is failing most of the time anyways. I was learning too. There was something instinctive about wanting to be teachable again. And I didn’t go home as a junior mechanic assistant thinking, “Why didn’t I use the sprocket wrench?” That didn’t bother me. It’s like, “I did my job. Now I can go and live my life.”

You came back to the business after a couple of years and got married and had your son, Silas; you shot a segment with both of them for the upcoming anthology feature “With/In.” What was that like?

I wanted to make a silent film when [Maven Screen Media’s] Celine [Rattray] first asked. I was so taken by the quiet here [in Vermont], as I always am when we come back. I wanted to make something about the environment we were finding out about firsthand — we were taking night walks, not talking intentionally, really just trying to listen and be aware of where we were at that moment. Silas shot pretty much all of it. We needed him, so we bribed him.

What was the bribe?

A new Telecaster [guitar] or something. Sushi. He shot most of it really, really well.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.