David Strathairn finds connection — and disconnection — in nomad lifestyle

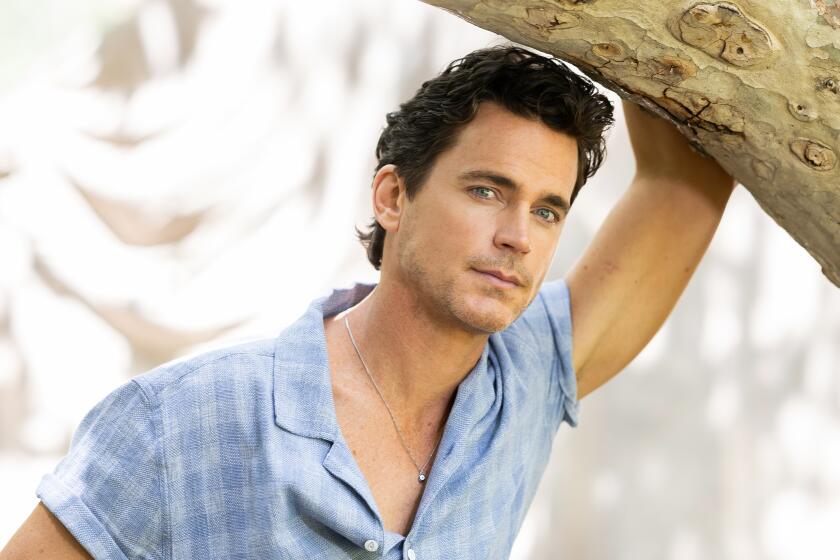

With a 40-plus-year career and an Academy Award nomination (for 2005’s “Good Night, and Good Luck), David Strathairn is guaranteed to raise the bar on any project he’s involved in. Rangy and reserved with a shock of white-steel hair, the San Francisco-born actor has proved versatile as — among dozens of other roles — a supportive manager (“A League of Their Own”), an abusive husband (“Dolores Claiborne”), a blind tech geek (“Sneakers”) and, now, a possible love interest for Frances McDormand’s uprooted Fern in “Nomadland,” which opens this week. He Zoomed into a call recently from Canada, where he’s shooting Guillermo del Toro’s “Nightmare Alley.”

We’ve all been isolating during the pandemic, but “Nomadland” is about another kind of isolation. What did you know about it before the movie?

I thought the book [“Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century,” by Jessica Bruder] was a very important document. It’s about the sort of diaspora of people living in their cars across this country, and I’m not sure that’s on a lot of people’s radar. But there is a vast amount of people who’ve made the choice due to circumstances to live this way. It’s an extraordinarily connected, and at the same time disconnected, community.

Are we meant to envy this independent lifestyle? Or pity that in a wealthy country many of them are forced into being nomads?

You may think, “Living in a car, how desperate is that?” but I would say that the people, the nomads, do not feel sorry for themselves. They’ve made this choice, and they live it to the fullest. It requires a lot of resiliency and inventiveness. I didn’t sense anyone feeling sorry for themselves. It’s not a political film; it’s the story of one woman. It’s a wonderful backdrop on part of American culture.

The film was made with a very small crew and cast; what did you like about that aspect?

At any given time, there were maybe six to 15 people, not including the other nomads. It was working out of trucks and vans, a very hip-pocket kind of production. Not that it looked like it was out of your back pocket. It proves you can do some brilliant, beautiful work with a minimum of technical crew. It was impressive to see this little roving band of filmmakers accomplish this.

I imagine it harkened back to your earliest days, making movies with director John Sayles.

It was like a throwback, specifically to “[Return of the] Secaucus Seven.” I hope I know a little more of the lay of the land than I did making “Secaucus,” but it felt very similar. Back then, I looked at it as a bunch of friends working together, telling a great story. John tells stories that in many ways are like “Nomadland” — he looks at people who are maybe on the margins of society, at least those under the pressure cooker of society.

You had a bit of a nomadic part to your life — before you started making movies, you hitchhiked across the United States?

I was going from summer theater to summer theater. I look back on those days as being, “Wow, that was a really special opportunity,” which doesn’t exist today. Now, people don’t trust people they see on the side of the road or hitchhiking. They ignore them or dismiss them. This was back when you could get rides across the country. You had to keep your wits about you, but it was a great way to see the country.

You’ve had this a wide-ranging career, but mostly you’ve been a terrific supporting player. Do you feel like that is “settling,” or is it a compliment to be working no matter what kind of role you get?

It’s a double-edged sword, because you get chosen by what you do — and for the most part, what you are chosen to do is out of your hands. You get pigeonholed after a while, and you understand that. But it’s a wonderful thing, being asked to be a character actor. You get a lot of hats out there you can play with.

Did having the lead role in 2005’s “Good Night, and Good Luck,” which earned you an Oscar nomination, change things for you?

For a moment, they did, but in the long run — no. I don’t think it changed my stripes or spots or whatever we’re born with or see ourselves in. It was an extraordinary experience, it was a wonderful chance to investigate [Edward R. Murrow] and work with George [Clooney] and Grant [Heslov], and that was one of those gifts from out of the blue. But it didn’t change my trajectory.

Are there still some things you’d like to do professionally, roles you’d like to play?

Nothing that’s really pressing on my brain. I just want to be involved with good stories for as long as I can.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.