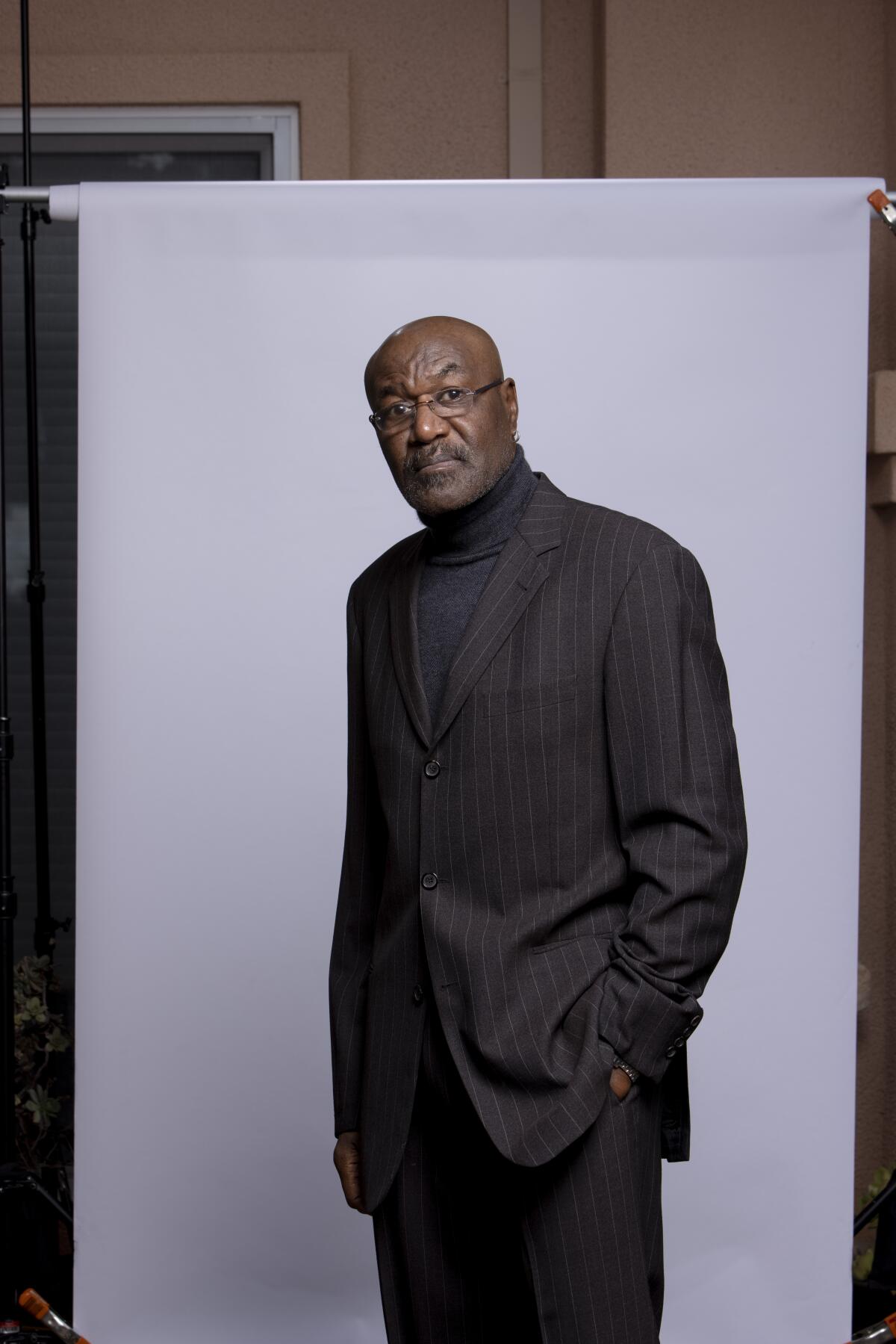

Delroy Lindo: Broken ex-soldier in ‘Da 5 Bloods’ is ‘Shakespearean tragic character’

Delroy Lindo was 16 and living in London during the height of the Vietnam War. “Of course I knew about the war,” he says, “but I was totally obsessed with acting. I didn’t really begin my education about the Vietnam War until I started preparing for ‘Da 5 Bloods.’”

That preparation yielded major dividends. In his fourth collaboration with writer-director Spike Lee, Lindo lends a spooky intensity to Paul, the PTSD-afflicted Vietnam vet who reunites in present-day Ho Chi Minh City with three Black war buddies and his son. Their mission: retrieve gold buried in the jungle decades earlier by CIA operatives.

The film pushes Lindo into uncharted realms as a broken ex-soldier, riven by paranoia, who talks to ghosts and ultimately goes mad. Lindo says, “I don’t want to say it’s ‘once in a lifetime,’ because I hope there are other experiences [in the future], but from the beginning, I was keenly aware that this was a phenomenal part,” Lindo says. “Paul’s a Shakespearean tragic character, and it doesn’t get any better than that.”

The London-born actor, on a break from filming the fact-based Black western “The Harder They Fall,” recently got on the phone from his Bay Area home to revisit the personal connections and stormy weather behind his “Da 5 Bloods” star turn.

Since you didn’t experience the war firsthand, how did you get into your character’s anguished head space?

I have two cousins who are Vietnam vets. I called them up. I told them about “Da 5 Bloods.” They came and hung out with me for the day. They both have suffered from PTSD, so being able to watch their body language and listen to what they said gave me this compendium of information that became central to what I was about to do. And also, one of my cousins gave me a shoe box filled with photographs he took in Vietnam.

Riz Ahmed, George Clooney, Delroy Lindo, Gary Oldman and Steven Yeun take us inside their new films and open up about their insecurities.

Oh, my God.

Oh, my God is right. I mean, full of photographs. Within the first week and a half in Vietnam, he was in-country, fighting. He took these pictures on his Kodak, or whatever, and I went through every single one of them.

Filming in Thailand, you, as Paul, march into the rainforest at one point and deliver this wild Lord’s Prayer-meets-Marvin Gaye stream-of-consciousness rant. How did that sequence come together?

When I walked off into the jungle, the wind kicked up, and the trees started swaying back and forth, just as I’m emotionally swaying back and forth. That was supposed to be the end of the scene. Me quoting the 23rd Psalm and screaming Marvin [Gaye] lyrics — none of that was scripted. I just articulated what I was feeling. Spike kept the cameras rolling, and the sound man picked it up.

Wait a minute. That monologue just came to you in the moment?

Yes! You don’t believe me, ask Spike. In the script, I call my son a backstabber and say, “I’m out.” Everything that transpires after was improvised. Afterward, we got caught in torrential rain on the way back to base camp. A tree fell down in front of the van, and we had to wait for someone to clear the tree. That’s how intense the storm was.

In keeping —

In keeping with the incendiary nature of the work. I say incendiary, but it was God. It was that spiritual component. There were a number of moments like that during production.

You seemed to share this almost brotherly bond on-screen with the late Chadwick Boseman, who portrays your revered leader, Stormin’ Norman. When did you first meet Mr. Boseman?

We met briefly in his camper after he landed in Thailand. A day or so later we did the scene.

That was it?

That was it. I’d been on the film five or six weeks at that point, so I was in a groove. Any actor will tell you, the first couple of days on a film set you’re still finding your feet, getting your bearings. So for this cat to show up literally on his first day of work and produce like that — it’s a testament to who Chadwick was as an actor. From a craft standpoint, a creative standpoint, it kind of takes your breath away.

You and Spike Lee have developed an extraordinary rapport over the decades. What’s the key to your collaboration?

He trusts me.

How does that trust affect your performance?

It’s freeing. So freeing — to the point where I know I can walk off into the jungle and just go with what I’m feeling. I don’t know if it’s going to make the final cut, but I do know that Spike gives me the latitude to express myself. For an actor, that’s profoundly liberating.

As the first major movie to look at the Vietnam War and its aftermath from an African American perspective, “Da 5 Bloods” resonates powerfully right now, amid this country’s Black Lives Matter reckoning. You’ve made a lot of movies. Does this one feel different?

I can’t overstate how special this film is to me. It’s scalpel-sharp as a cultural moment, just like “Black Panther” and “Malcolm X” were cultural moments. And that’s why I went to acting school in the first place, man, to be part of making the kind of work that has an impact on society.

The Delroy Lindo mixtape

Every day on his way to “Da 5 Bloods” set in Thailand, Delroy Lindo got into character as the volatile Paul by listening to a mixtape of period songs. “I guess you’d call it a personal soundtrack, and it’s something I do on every film,” he says. “Music is a fundamental part of my process, because it helps me acclimate to the world of the narrative. Along with other exercises, I use the mixtape to get myself into the space I need to be in so I can do the work.”

From his “Da 5 Bloods” playlist, Lindo singles out a specific track as an especially significant song. The Friends of Distinction’s 1969 “Going in Circles,” with its melancholy lyrics — “I’m an ever-spinning top, whirling around ‘til I drop.” The slow jam impacted Lindo on a personal level. “I included ‘Going in Circles’ because one of my cousins, a Vietnam vet, said that particular song meant a lot to him while he was in ‘Nam,” Lindo notes. “The song resonated for me, too, so it made total sense to include it on my mixtape. I used a slew of songs from the ‘60s and ‘70s, because they’re so evocative of the period and contain some very incisive sociopolitical lyrics.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.