Día de Muertos is not a season to mourn, it is a season to celebrate life. The holiday originates from Indigenous people such as the Olmecs, Toltecs, Mixtecs, Zapotecs, Mayans and Aztecs. In their traditions, these groups perform ceremonies to honor the dead and partake in harvests.

“The spiritual component comes from Indigenous cultures,” said Antonieta Mercado, a professor at the University of San Diego. “It is misleading to call Día de Los Muertos a day because it is a celebration that is linked to the harvest.

Here’s your guide for events in L.A. and O.C. counties that are bringing the community together to celebrate Día de Muertos.

Día de Muertos is celebrated throughout the month of October leading up to Nov. 1 and 2, and is largely observed throughout Mexico and other Latin American countries. One of the biggest activities for the holiday is building an ofrenda and placing objects and symbols on it to honor the dead.

The ofrendas that people make are meant to be bright so the souls of lost loved ones can find their way. Each of the items on an ofrenda is placed with a specific reason that correlates to Indigenous cultures.

Here is the meaning behind a few of the objects placed on an ofrenda:

Cempasúchils

One of the most recognizable items placed on ofrendas are the cempasúchil flowers that have a distinctive bright orange color. The cempasúchil is the official flower associated with Día de Muertos and was commonly used in Indigenous Aztec rituals to honor the goddess Mictecacihuatl, who is known as the Lady of the Dead.

“The vibrant flowers are used to attract but then also the scent is intended to help guide the dead to the altar,” said Denise Meda-Lambru, a doctoral candidate at Texas A&M University.

Water

Indigenous groups were greatly influenced by the earth and its elements during Día de Muertos celebrations. A cup or bowl of water is left on an ofrenda to represent purification. It also acts as a symbol to help cleanse the souls that are traveling back to the land of the living.

Pumpkins are known for a ghoulish grin and delicious taste. Their origins are rooted in Mexican history

There’s no symbol that screams Halloween more than the warm glow of an orange pumpkin. But as big a part of autumnal U.S. culture as they’ve become, their origins point a bit more south to Mexico.

“The water element is meant to cleanse the energies and then also quench the thirst of the dead that are coming to visit,” Meda-Lambru said. “The belief is that they’re coming to visit and you’re welcoming them.”

Candles

To symbolize the element of fire on ofrendas, candles are placed to help light a path for the souls to follow. The belief is that the souls are in the underworld in darkness and they use the light from the candles to travel to the living world. The candles are commonly placed in a row leading up to the ofrenda.

Food

Plates of food are placed on ofrendas to feed the souls as they come to visit. Indigenous people believed that souls have to make a long journey to the living world and can become hungry along the way. Some people prepare their loved ones’ favorite dishes and place them on the ofrenda. Corn is also commonly left on ofrenda to honor ancestors.

“You can see in many communities they place corn on the ofrenda because it’s a tribute, it’s a big ‘thank you’ for the ancestors that helped with the course of the harvest,” Mercado said.

Papel picado

Colorful strings of papel picado are hung on ofrendas to represent wind and air. The pieces of paper have holes and allow wind to flow through them, which symbolizes a soul’s journey to the living. The papel picado is also used to add color to the ofrendas.

“Papel picado is very thin and it sort of flies with the air and it moves and that’s the element of wind on the altar,” Mercado said.

Incense

People often burn incense on an ofrenda to help draw the souls in with the smell of smoke. From a religious standpoint, incense is also used to purify and cleanse the air.

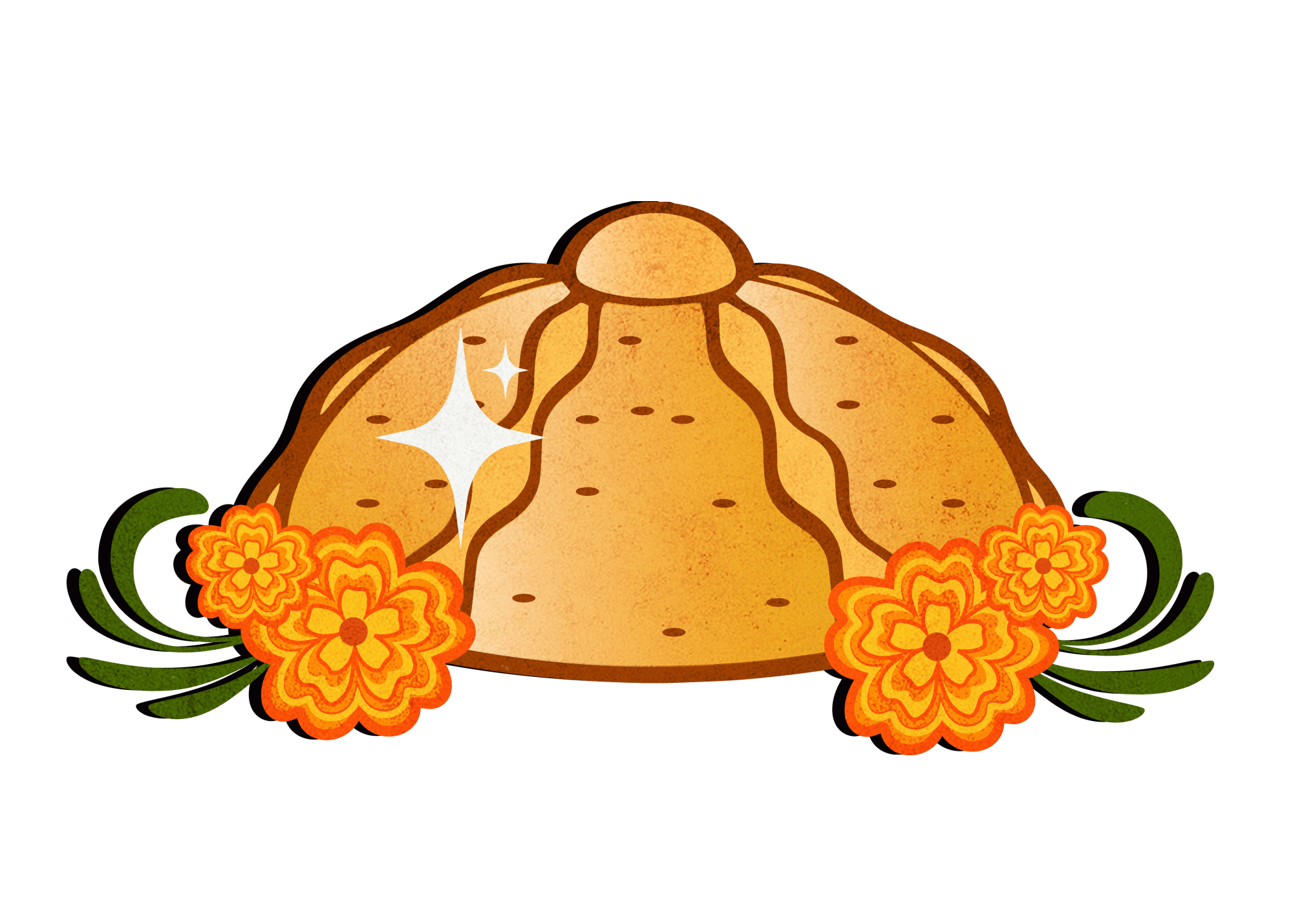

Pan de muerto

Pan de muertos is one of the foods most commonly associated with Día de Muertos and it also represents an offering of food for the dead. Most pan de muertos have a cross on top to signify death. Pre-colonial traditions of performing sacrifices influenced having bread with a heart and blood on top of it. After colonialization, a cross was placed on the bread instead.

Flower vendors in the Flower District of downtown L.A. prepare cempasúchils for ofrendas and Día de Los Muertos celebrations weeks in advance.

“[Pan de muerto] can often have bone shapes on it,” Meda-Lambru said. “Like the skulls, bread with these designs are meant to represent imagery of death and provide sustenance.”

Sugar skulls

Calaveras, especially in the form of sugar skulls, are commonly placed on ofrendas to represent death and rebirth. The calavera is an important symbol in Indigenous cultures because it is a physical representation of the underworld.

“Sugar was a crop that does have historical ties to the colonial era in the Americas,” Meda-Lambru said. “Skulls are also made of amaranth, a seed with a longer history in the Americas.”

Picture frames

Photos serve as a visual representation of the loved ones being honored on the ofrenda. The pictures also help encourage the souls to return by letting them know the ofrenda is dedicated to them.

Most of us know what Día de Muertos is but are unfamiliar with the history behind the tradition that is now celebrated each year.

With the colonialization of Europeans and the influence of Christianity and Catholicism, Día de Muertos became a syncretized celebration bringing together Indigenous elements as well as religious beliefs.

The spiritual belief of Día de Muertos is that the souls of those who have passed and are in the underworld are traveling back to the living world, and their souls are being welcomed by an ofrenda.

“The emphasis of being together in community, those collective spaces for grieving, for celebrating, for remembering the dead — is at the core of this,” Meda-Lambru said.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.